| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

Jun15

Afghan Opiate Trafficking through the Southern Route

Back to topTable of Contents:

1. Overview of Afghan opiate trafficking on the southern route

2.1 Opium production

2.2 Heroin production

2.3 Morphine Production

2.4 Acetic anhydride trafficking

2.5 Trafficking routes

2.6 Summary4. The Islamic Republic of Iran

5. Middle East and Gulf countries

12. Responding to the challenges of the southern route

Glossary

AFP Australian Federal Police AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome AND Anti-Narcotic Department, Jordan ANF Anti-Narcotics Forces, Pakistan ANSF Afghanistan's National Security Force AOTP Afghan Opiate Trade Project ARO Annual Report Questionnaire BBC British Broadcasting Corporation BKA Bundeskriminalamt, Germany CARICC Central Asian Regional Information and Coordination Centre CCP UNODC Global Container Control Programme CEN Customs Enforcement Network CEWG Community Epidemiology Work Group CMF Combined Maritime Forces CNPA Counter-Narcotics Police of Afghanistan DCHO Drug Control Headquarters, Islamic Republic of Iran DEA Drug Enforcement Administration, United States of America DELTA Database on Estimates and Long Term Trend Analysis DMP Drugs Monitoring Platform EMCDDA European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction EU European Union EUROPOL European Police Office FC Frontier Corps, Pakistan FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas GCC Arab States of the Gulf gm Grams ha Hectares HDI Human Development Index HIV Human immunodeficiency virus IDS Individual Drug Seizures IDU Injecting drug use INCB International Narcotics Control Board INCSR International Narcotics Control Strategy Report INTERPOL International Criminal Police Organization ISAF International Security Assistance Force kg Kilograms km Kilometres MAR-INFO An information system executed by the EU Council Customs Working Party MCN Ministry of Counter Narcotics, Afghanistan MNC Ministry of Narcotics Control, Pakistan MOI Ministry of Interior mt Metric ton No. Number NCA National Crime Agency, United Kingdom NCB Narcotics Control Bureau, India NDLEA Natio nal Drug Law Enforcement Agency, Nigeria RCMP Royal Canadian Mounted Police S.A.R Special Administrative Region SOCA Serious Organised Crime Agency UN United Nations UNDP United Nations Development Programme UNDSS United Nations Department of Safety and Security UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime USA U.S. dollar WCO World Customs Organization ZKA Zollkriminalamt

Key findings

- Afghan heroin is trafficked to every region of the world except Latin America. The Balkan route (trafficking route through the Islamic Republic of Iran and Turkey) has traditionally been the primary route for trafficking heroin out of Afghanistan. |1| However, there are signs of a changing trend, with the southern route (a collection of trafficking routes and organized criminal groups that facilitate southerly flows of heroin out of Afghanistan) encroaching, including to supply some European markets.

- Unlike the northern or Balkan routes that are mostly dedicated to supplying single destination markets -the Russian Federation and Europe respectively, the southern route serves a number of diverse destinations, including Asia, Africa and Western and Central Europe. |2| It is therefore perhaps more accurate to talk about a vast network of routes rather than one generalflow with the same direction.

- The Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan face a tremendous challenge in dealing with the large flows of opiates originating from Afghanistan to feed their domestic heroin markets and to supply demand in many other regions of the world. The geographic location of the Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan makes them a major transit point for the trafficking of Afghan opiates along the southern route.

- Seizures further out in the Indian Ocean have highlighted the potential for traffickers to send sizeable shipments using boats departing from unofficial ports and jetties along the coast of Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan. Maritime trafficking seemingly presents opportunities to smuggle large quantities of heroin (or opium) to third countries quickly, while trafficking using air transport would involve smaller quantities of drugs per consignment in order to avoid detection.

- The prominence of African sub-regions as potentially important consumption and transit zones for the trafficking of Afghan heroin along the southern route is a major finding of this report. The wide array of cargo and air links that have opened up to and through Africa offer many opportunities for traffickers. The information available at present suggests that different regions of Africa are developing important roles in facilitating the transit of southern route heroin, and networks from those regions have taken control of some trafficking routes.

- The Gulf region is another heroin market and a trans-shipment hub for the trafficking of Afghan opiates along the southern route. In Europe, networks operating between Pakistan and Europe have become more dominant in recent times with the United Kingdom, Belgium and the Netherlands as notable targets for trafficking via the southern route. A number of other countries that in the past were mainly being served by the Balkan route, including Spain and Italy, have recently noted Pakistan and African countries as prominent sources of opiates in transit from Afghanistan. Although it may be too early to identify this as a trend, heroin trafficked via the southern route has also been seized in East and Central Europe, with specific seizures in Slovenia and Ukraine, showing the need to closely monitor developments in this regard.

- India appears to be the main destination market for Afghan heroin smuggled along the southern route to South Asia while the largest potential revenues for southern route traffickers in East and South East Asia (ESEA) are to be found in China.

- Sources of heroin have fluctuated in Oceania, between Afghanistan and South East Asia, with a predominance of the latter in recent years. North America is similarly not a primary consumer of Afghan heroin, but It can provide a lucrative niche for some trafficking groups, in particular in Canada where most of the heroin seized originates from Afghanistan.

- Recent developments in illicit trafficking of opiates along the southern route highlight the importance of mutual cooperation between countries, regions and organisations. The Triangular initiative (that promotes collaboration between Afghanistan, Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan) has already demonstrated the tangible results of regional cooperation.

Map 1: Indicative heroin trafficking routes along the southern route Note: The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Sudan and South Sudan has not yet been determined.

Source: UNODC elaboration, based on seizure data from Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) Individual Drug Seizures (IDS) and Annual Report Questionnaire (ARO), supplemented by national government reports and other official reports

Introduction

Afghan heroin is trafficked to every region of the world except Latin America. Trafficking heroin from production centres to heroin markets requires a global network of routes and facilitation by domestic and international criminal groups. Some routes appear to develop as a result of geographic proximity, while others are associated with lower risk, connections between migrants, higher profits or simpler logistics. This network is becoming increasingly intricate, but longer-lasting patterns are apparent. This report presents insights into the southerly flows of heroin out of Afghanistan - a collection of trafficking routes and organized criminal groups that constitute the southern route. UNODC has identified the northern route, the Balkan route and the southern route as the main heroin trafficking routes out of Afghanistan. |3|

The southern route is clear in its central thrust out of Afghanistan and through Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran. |4| At the eastern and western fringes of that flow, and as trafficking proceeds further afield from South Asia, it becomes more challenging to distinguish the southern route from, for example, flows that could be pertaining to the Balkan route, or the tangle of different pathways supplying and transiting through the Middle East. The trafficking of Afghan opiates to East and West Africa is increasingly more clearly observable. Yet to the east of Pakistan, Afghan opiates |5| seem to supply markets in South Asia, South-East Asia and Oceania that are also supplied by Myanmar, in proportions that vary geographically and over time. These proportions and changes are not always clear-cut, but have important implications for those trafficking Afghan opiates and those working to stop them.

Overall, therefore, drawing a line around the southern route involves some arbitrary distinctions at the margins. Despite the difficulty of delineating its specifics, the southern route is a useful concept and focus for analysis, which can help to provide answers, for a number of reasons. Firstly, it is reasonable to presume there is some coherence and consistency among trafficking networks and drivers of the Afghan opiate trade along these trajectories, particularly since they begin with a relatively small number of movements out of Afghanistan and through the Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan.

Secondly, the collection of trafficking efforts that form part of the southern route would appear to deliver a large proportion of opiate flows dispatched from Afghanistan. A sprawling, transnational trade in Afghan opiates has to be categorised to some extent in order to focus on important features. Lastly, most findings will occur in specific places. This report aims to provide answers concerning the southern borders of Afghanistan and the popular routes transiting the Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan. For places further afield, it helps to identify how they are linked to specific supply chains that trace back to the southern route's centralthrust.

Unlike the northern and Balkan routes, which are mostly dedicated to single destination markets, the southern route serves a number of diverse destinations, primarily Europe, Africa and Asia, and to a lesser extent even markets further afield in the Americas. The only major opiate destination market seemingly not targeted through this route is the Russian Federation. It therefore seems more accurate to talk about a vast network of routes rather than one direct flow. Moreover, the southern route relies heavily on maritime trafficking while both the Balkan and northern routes are mostly overland trajectories. With the possibility that global container throughput will hit one billion TEU (twenty-foot equivalent unit) in 2020, it is possible that more traffickers will turn to this mode of transportation to blend into the global commodity flow, |6| which would favour the southern route as a means of exporting opiates from Afghanistan into global maritime trade networks.

Map 2 illustrates the basic geography of the current analysis. Where relevant, the report also discusses drug flows or issues that are beyond the scope of the southern route, but which may affect it in some way. Generally, the focus of the report remains on the southern route itself, as a major example of illicit transnational opiate trafficking, and aims to identify patterns amenable to action by UNODC stakeholders.

Map 2: Indicative Afghan heroin trafficking routes Source: UNODC elaboration, based on seizure data from Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP), individual Drug Seizures (iDS) and Annual Report Questionnaires (ARO), supplemented by national government reports and other official reports.

1. Overview of Afghan opiate trafficking on the southern route

This chapter identifies some cross-cutting issues and themes apparent in Afghan opiate trafficking along the southern route. It sets the scene for the following chapters, which have a geographical focus, while the final chapter explores emerging threats and challenges and suggests the way forward.

Sources and data

The report draws from the following data sources:

- Data submitted by Member States to UNODC through the Annual Report Questionnaire (ARO) on an annual basis.

- Drug seizure cases reported to UNODC through the Drug Monitoring Platform database (DMP). This is an online platform for officials to report and visualize seizure data, including data gathered from media reports and other open sources.

- The UNODC Individual Drug Seizure database (IDS). This contains data on significant individual drug seizures as reported by Member States. |7|

- UNODC Database on Estimates and Long-Term Trend Analysis (DELTA) aggregates official drug seizure data provided by Member States, inter alia, via the ARO.

- Presentations and reports from Member States.

- Open source documents and information (duly referenced).

It is important to note that there is limited information regarding individual drug seizures from the Islamic Republic of Iran and from several countries in Africa. Even where seizures are reported, there is often sparse information on the destinations, methods of trafficking or other variables thatwould support deeper conclusions and enable to identify trafficking patterns. In some instances, seizure cases have been excluded from analysis due to the lack of detailed related information.

Interpreting drug seizure data

Despite gaps in datasets, the drug seizure data available to UNODC is relatively abundant compared to other sources on drug trafficking groups. Analysing seizure data, however, is not always straightforward,for a number of reasons.

Drug seizures are a direct indicator of drug law enforcement activity and therefore reflect their priorities and resources. As is the case in this report, seizures are often considered as an indirect indicator of drug flows and availability when linked with other information, based on the fact that law enforcement can only make seizures where drugs are present. On the other hand, geography and infrastructure influence the traffickers' choice of routes and methods. Where topographical features or facilities such as ports can influence traffickers' options, there may be greater confidence that a cluster of seizures indicates an important point in the underlying opiate trade. |8|

Leaving aside geography, seizures can also follow criminal connections. This occurs primarily because, in the course of law enforcement investigations, the arrest of one trafficker can provide tips pointing towards their associates, which may in turn lead to further drug seizures in relation to that particular network. The resulting pattern ofseizures may follow criminal networks more than geographicalcontours.

Finally, seizure information is obviously retrospective, suggesting where trafficking attempts have been rather than where trafficking may be taking place now. Large sets of data generate patterns reflecting a combination of variables including criminal networks, geography, law enforcement and other unknown factors, but may not always indicate where trafficking will take place in the future. Indeed, there are reasons to believe that seizures in one place will predict reduced trafficking activity there in future. For example, traffickers may shift away from an area that has been targeted repeatedly. This could even lead to a situation in which the number of seizures may be rising in a certain location because it is receiving increased law enforcement attention, even though trafficking may have actually decreased.

Given the challenges ofinterpreting seizure data, this report uses the information in three ways:

1. To describe patterns identified in the quantitative data.

2. To combine quantitative data with qualitative information in orderto suggest potential trends regarding routes, methods and actors of the opiate trade.

3. To indicate possible trends in the opiate trade that may be worth researching further.

Trafficking risks and rewards

Figure 1: Wholesale price of heroin (ofunknown purities) as it is smuggled along the southern route Note: Figures are rounded; prices are not purity-adjusted

Source: Source: World Drug Report 2014 (UNODC) and information provided by Ghana in a personal communicationAs previously described in relation to interpreting seizure data, factors such as physical geography, human infrastructure, criminal networks and law enforcement all affect trafficking patterns. User tastes, traffickers' experiences or habits, as well as their access to information and the personal circumstances of individual actors are among the variables that may play an important role in deciding what to traffic, where and how. These variables are of different nature and related data are scarce and patchy, if at all available.

Risk and reward are two common values that shape the traffickers' behaviour. To begin by using them in a simple model, the following would be logical statements, presuming all other variables remained unchanged:

- More effective law enforcement at a particular location increases the risk to traffickers and it will therefore decrease trafficking. If this holds true, one would expect that the high volume of seizures by Pakistani authorities in Balochistan in recent years should make it less attractive to smuggle drugs through Balochistan.

- A higher price of heroin in a particular place increases the reward for trafficking to that place and it will therefore increase trafficking of the drug. If this holds true, one would expect that increased retail prices in Western and Central Europe in recent years |9| would encourage traffickers to dedicate more effort to supply users there.

- Growth in the number of heroin users in a particular location increases the reward for trafficking to that location and it will therefore increase trafficking of the drug. If this holds true, the growth in heroin use that is perceived to be occurring in West Africa |10| will increase its attractiveness to traffickers.

An additional layer ofcomplexity would consider relative risks and rewards. For example:

- More effective law enforcement at a particular location will not increase the relative risk to traffickers if enforcement at alternative locations also becomes more effective. If the seizures in Balochistan are matched by increased seizures across Pakistan, the proportionate volume trafficked via Balochistan would not be expected to change.

- If an increased price of heroin reflects increased pressure from law enforcement (increased risk), then trafficking may not increase. This may have occurred in South Eastern Europe in 2011-2012 although the tighter enforcement occurred largely upstream, in Turkey. |11|

- An increasing number of heroin users would not generate greater rewards for trafficking if this trend is accompanied by a decrease in price. For example, if Afghan heroin becomes established in West Africa and becomes cheaper as the result of greater transit supplies, it may not on its own attract stronger attention by traffickers as a heroin market.

It may also be important to emphasise how different actors along the southern route assess risks and rewards differently. For example, a greater number of arrests would be expected to reduce the attractiveness of other illicit markets, but if enforcement risks are higher across all options facing those who are orchestrating the trafficking attempts, then itwill not shift these organizers' balance of risks and rewards. Crucially, these changes depend on information flows; for instance, a low-level drug courier may not know about recent seizure patterns and therefore may not perceive their risk accurately. Or, an organizer may accept a marginal reduction in their own reward by paying a courier slightly more, which serves to shift the courier's assessment of rewards dramatically without changing much the situation facing the organizer. Considering such scenarios is useful to highlight the importance of individual decision-making, which is based on perception, rather than on objective facts alone.

With the potential to generate extremely complex models of trafficker decision-making, the challenge for this report is to choose a level of complexity that can be supported by data and is useful for actionable conclusions or further investigation. This largely depends on the context and specific issue being explored; the analysis presented in the chapters that follow suggests a few trends affecting the southern route overall, which are summarized in the next sections.

Diversification

A trend in many drug markets around the world is towards diversification. |12| This is occurring across several dimensions and creates greater complexity for both the analysis of the situation and law enforcement responses to opiate trafficking along the southern route.

Drug types

A first kind of diversification is in the proliferation of drug types available in a given market. When considering the breadth,volumes and impacts of the southern route,diversification of drug types in consumer markets makes analysis more difficult. A larger number of possibilities need to be addressed in relation to users' propensities to substitute between drugs. Predicting how trafficking groups will respond to enforcement or price changes becomes less certain when there are more products on the market. Predicting the evolution of product market shares is trickier when it is likely that new products will appear.

Along the southern route, diversification is apparent in several places. For example, drug users in West Africa seemed to use relatively negligible quantities of heroin until recent years. Now, however, there is evidence that they have access to Afghan opiates. In a different example,an emerging phenomenon among opioid-dependent drug users in the United States of America is that synthetic opioids are being partially replaced with heroin, driven by the increased availability of heroin in parts of the United States, and the lesser costs for regular users to maintain their dependency. |13| Overall, it appears that diversification of drug types affects southern route traffickers primarily in two ways. First, new drug markets are emerging as routes proliferate, particularly in Africa. Second, in established drug markets, the availability of alternative drugs is adding to competition for southern route traffickers. The balance of revenues, profitability and participating groups will vary by location, but this report suggests that diversification of drug types contributes to the sense of flux in this sector of the Afghan opiate trade.

Sources of supply

Even for a single type of drug, such as heroin, the development of the southern route suggests that sources of supply are diversifying. The most prominent cases are at the extreme ends of the southern route's networks, such as the USA, Australia and China. For example, since the 1990s the USA has relied on Latin America or Myanmar for its heroin. In recent years, greater importation and distribution of southern route heroin is reportedly associated with the growing participation in the Afghan opiate trade by nationals of countries in West Africa. Although the USA reports that heroin from South-West Asia remains a minority share of the market, |14| there would appear to be interest among southern route traffickers to ship consignments to the USA.

It is unclear whether there is any coordination between groups that favour different sources of supply. It seems plausible that heroin of different origin may mingle in some markets but remain well separated in others, depending on the structure ofopiate trafficking in different locations and across different criminal networks.

In Australia, the number of heroin users is relatively small and until the 1990s it seems that they were almost entirely supplied from Myanmar. In the last decade, however, tests of seized samples show changes from year to year in the proportion of heroin from South-West Asia compared to South-East Asia. |15| Again, it is unclear if there is any bifurcation in the distribution system between retailers and/or wholesalers with links to one source or the other.

China is geographically connected to both Afghanistan and Myanmar. There has generally been an evidence-based assumption that Myanmar is the dominant supplier to Chinese heroin users, but in the 2000s there were reports of Afghan heroin becoming more important as a source of supply. In recent years, China has estimated that Afghan heroin is maintaining a sizeable but still minority share of the market. It is reasonable to expect that most of this is trafficked overland via neighbouring Central Asia or northern Pakistan, but this report demonstrates that southern route traffickers also play a role in moving heroin to China - including Hong Kong - by air and sea.

Trafficking routes

With sources of supply diversifying, many markets are experiencing a parallel diversification of trafficking routes. Moreover, even with a focus only on the southern route, there has been a proliferation of trajectories connecting users to Afghanistan, Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran. For example, Italy used to rely almost entirely on heroin trafficked along the Balkan route by land and sea. This has not ceased, but routes seem to have diversified to include more direct shipments from South-West Asia by sea, mail and air, as well as supplies through Africa.

To the East, between Pakistan, the Islamic Republic of Iran and Asia, there is evidence of direct shipments by sea (for example, from Pakistan to Malaysia), trans-shipment via Middle Eastern ports, direct air courier attempts (for instance,from Pakistan to Bangkok), circuitous air courier attempts via the Middle East,geographically dispersed postaltrafficking, and trans-shipment via Europe, South-East Asia and onwardsto Australia.

In North America, attempts to supply Canada in recent years have included incoming Rights from Africa and Europe, cargo by sea from Pakistan and mail arriving from multiple transit locations.

The migration flows across the globe, transport routes and communication connections appear to be important factors generating a profusion of potential supply lines for traffickers and supporting their capacity to use them. In any given case or pattern of trafficking along the southern route, a familiar set of enablers may be highlighted, but the web of supply lines overall is becoming more diverse. This has implications for law enforcement efforts, most notably in requiring cooperation among countries that may otherwise have little contact with one another. It may also be impacting the profitability and stability of trafficking networks, although this is difficult to gauge.

Participants

In terms of the nationalities and capacities of traffickers, a continuing trend apparent throughout this report is the involvement of nationals of African countries across several southern route countries, from producer to transit and destination. |16| In the heroin arrests data reported to UNODC, Pakistani nationals also appear to be involved in major markets such as Western and Central Europe. |17|

Available information indicates that trafficking syndicates from regions such as West Africa are active in almost all regions associated with the southern route. More information on these networks, which might be involved in the trafficking of different types of drugs, is necessary to design effective responses. Member States report to UNODC a greater need for intelligence sharing in this area,for example between destination countries such as Australia, countries in transit regions such as East and South-East Asia, and source countries in South-West Asia.

The rise of nationals of African countries is a prominent example of the shifting opportunities and market power that are accompanying the diversification of routes out of the Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan. A reasonable hypothesis to investigate is that globalisation increases opportunities for suppliers and retailers to disintermediate the many middlemen that have been a feature of drug trafficking out of Afghanistan. An important example on the southern route may be apparent in the increase of direct shipments from Pakistan to Europe, which among other consequences would reduce the participation and profits available to traffickers in Turkey and the Balkans. On the other hand, the growing use of transit points in Africa highlights that there are still opportunities for new middlemen to insert themselves into southern route supply lines.

Methods of trafficking on the southern route

There are four basic transportation methods monitored in this report, along with other sub-types, a) Trafficking by post, b) Trafficking by sea (including in cargo and small boats), c) Trafficking by air (in cargo, luggage and hidden on the body) and d) trafficking by land (including in vehicles through trade crossings and unguarded borders, in luggage and hidden on the body).

The furthest reaches of trafficking by land on the southern route appear to be through Pakistan into India and through the Islamic Republic of Iran to its southern coast. The major routes in which trafficking by land is dominant are through Balochistan province of Pakistan and the south-eastern provinces of the Islamic Republic of Iran (see Figure 1).

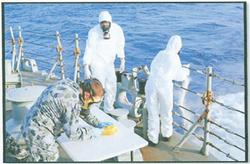

At sea, there are increasing numbers ofopiate seizures (mostly heroin) related to the use of the coastal areas in Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran. Sea and dry ports in South-West Asia have also seen an increase in general trade. In addition to official ports, traffickers use smaller jetties to move heroin to the Gulf region, the Gulf of Oman and further south to East Africa. Outside Afghanistan, Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran, the largest seizures by volume have occurred at seaports or on the high seas, indicating that trafficking by sea remains the transportation method for smuggling larger quantities of heroin. Large maritime seizures made in Europe also indicate that significant heroin shipments are not detected at points of departure.

Map 3: Location of opiate seizures (opium, heroin, morphine) in the coastal areas of Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran, as reported to UNODC presented in government reports and the media, 2010-2013 Source: UNODC Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS)

Interceptions of opiate shipments by air and mail suggest that these methods have become increasingly popular for southern route traffickers. Although the average quantity seized is small, the sheer number of shipments intercepted indicates that the aggregate volumes trafficked using these transportation methods may be large.

2. Afghanistan

In recent years Afghanistan has accounted for around 80 per cent of global heroin production |18|. This situation is intertwined with a number of other challenges facing the country, particularly issues related to governance and security. The rule of law does not extend to all regions of the country because of the dominating presence of anti-government elements in many provinces, notably in the south of the country. This provides a conducive environment for opium production and for morphine and heroin processing and trafficking. |19| After many years of drug production, Afghanistan has one of the highest opiate prevalence rates in the world with 2.65 per cent of population reportedly abusing opiates. |20|

Map 4: Afghanistan security level district map, 2014 Source: United Nations Department of Safety and Security (UNDSS)

The Afghan opium economy is best conceptualized as multiple industries producing various products for different markets. Afghan opium poppies are cultivated and processed to then be sold as opium, morphine and various grades of heroin. Each of these products have domestic and export markets and different regions within Afghanistan supply products for different domestic and export markets. The focus of this report is on the southern route; this chapter will also analyse some general production and trafficking trends in Afghanistan to provide context from which a clearer understanding of the role of the southern route can be developed.

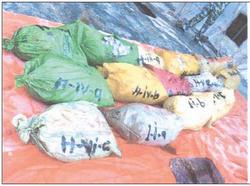

Major opiate seizures in Afghanistan 2011-2013 Major opiate seizures in Afghanistan point to the size of the industry and the difficulties the region faces in stemming the flow of opium, morphine and heroin out of Afghanistan along the southern route. Below are some of the major seizures made between 2011 and 2013.

- 700 kg in February 2011: Afghanistan National Security Force (ANSF) and the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) conducted a counter-narcotics operation in the Achin district of Nangarhar province and discovered an illicit heroin processing laboratory and weapons cache. 700 kg of heroin, 100 kg of opium, 210 kg of acetic anhydride and 50 litres of ammonium chloride were confiscated.

- 10,800 litres of morphine solution in September 2011: the seizure was made near Shahtut, in the Bahran district of Helmand province. Three large drug-processing laboratories were destroyed. Over 5 tons of precursors were seized along with 100 kg of heroin, 4 metric tons (mt) of morphine base and 80 kg of illicit morphine, 5 heroin presses,over 300 55-gallon drums and 6 generators were also seized.

- 190 kg in February 2012: ANSF seized 149 kg of heroin hydrochloride, 41 kg of heroin base and 51.5 kg of opium. Two suspects were arrested in the Washir district of Helmand province.

- 240 kg in September 2012: during a three-day operation in the Washir district of Helmand, coalition forces recovered a large amount of narcotics, weapons and explosives. This included over 240 kg of heroin and 300 kg ofopium.

- 104 kg in September 2012: in Chakhansur district, Afghan-led security forces seized 560 kg of opium, 104 kg of heroin and arms. Two individuals were detained, under suspicion of facilitating the movement ofweapons and narcotics across southern Afghanistan,.

- 600 kg in January 2013: Counter-Narcotics Police of Afghanistan (CNPA) seized 600 kg of heroin and arrested two suspects.

- 833 kg in November 2013: in Nangarhar province, four laboratories were seized and thousands of kilograms of heroin, opium and morphine were confiscated.

- 252 kg in December 2013: heroin was seized in Nimroz province from a motor vehicle.

Despite efforts by the Government of Afghanistan and the international community, opium-poppy cultivation in Afghanistan has increased in recent years. In 2014 the area under opium-poppy cultivation was estimated at 224,000 hectares |21|, a record high and a rise of around 7 per cent compared with 2013. The vast majority (89 per cent |22|) of opium-poppy cultivation in 2014 took place in nine provinces in the south and west of the country.

Map 5: Opium cultivation in Afghanistan, 2014 Source: Afghanistan Opium Survey 2014, UNODC

Many factors contributed to the high Level of opium-poppy cultivation in 2014, including the decrease in eradication efforts by 63 per cent from 7,348 hectares in 2013 to 2,692 hectares in 2014. |23|

In accordance with the increased area under cultivation,opium production spiked to 6,400 tons in 2014,an increase of 17 per cent from 2013, when it totalled 5,500 tons. UNODC estimates suggest that 62 per cent of opium is processed into heroin, with the remaining 38 per cent being left unprocessed |24|. Scarce data is available as regards the purity of heroin exported from Afghanistan and when considering heroin of export quality produced, an average purity of 52 per cent is assumed for wholesale. |25|

Figure 2: Opium production and heroin seizures in Afghanistan, 2004-2013 Source: UNODC World Drug Report 2014

The amount of opium interdicted annually remained below 60,000 kg between 2006 and 2011, before rising sharply in 2012 and 2013. Local opium markets are responsible for driving the majority of the movement of opium in the region, |26| but given the large quantity in circulation it is possible that a portion is being used for further processing into heroin in transit locations before being trafficked to destination countries.

Figure 3: Seizures of opium, morphine and heroin in Afghanistan 2004-2013 Source: UNODC Annual Report Questionnaire (ARO) and Database on Estimates and Long-term Trend Analysis (DELTA)

In Afghanistan, the Helmand province reports the largest amount of seized opium; other provinces in the south and south-west bordering the Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan such as Herat, Nimroz, Kandahar,Zabul and Uruzgan, also reported multi-ton seizures during the 2010-2013 period. This aligns with the regional data on seizures,with the majority of opium seizures taking place in neighbouring the Islamic Republic of Iran. It is likely that cross-border movements of opium use the same routes as heroin and morphine exports but remain within the region for local use or may undergo further processing outside Afghanistan. |27|

Map 6: Location of opium seizures in Afghanistan as reported to UNODC and presented in government reports, 2010-2013 Source: UNODC Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS)

The main opium-producing regions in Afghanistan also serve as major opiate processing Locations. The accessibility of raw materials, the insecurity of the regions and proximity to transit countries make them optimal sites for establishing processing laboratories.

Figure 4: Heroin laboratory interdictions in Afghanistan (Helmand)

Source: CNPA Afghanistan

According to CNPA data, nearly two thirds of the heroin laboratories in the country are located in the south, with other major sites in the western provinces as well as Nangarhar in the East and Badakhshan in the north. |28| Table 1 provides information on the destruction of laboratories from 2012 to 2013.

Table 1: Heroin Laboratory Destruction in Afghanistan 2012-13

Province 2012 % of 2012 Total 2013 % of 2013 Total Uruzgan 3 4.1 - 0.0 Badakhshan 7 9.6 12 19.7 Farah 3 4.1 1 1.6 Kandahar 3 4.1 6 9.8 Nangarhar 9 12.3 11 18.0 Helmand 48 65.8 31 50.8 TOTAL 73 100.0 61 100.0 Source: CNPA, February 2014 - data for previous years was unavailable at the time of writing

Heroin seizures have fluctuated in recent years with a peak of 10,983 kg in 2011,followed by seizures totalling 7,262 kg in 2012 and 7,156kg in 2013. Despite this decrease from 2011 to 2013, over the long-term the figure for 2012 remains relatively high. This overall increase in heroin seizures is mirrored by a similar surge in seizures of morphine in 2011 and 2012, which is later addressed further. The majority of the heroin and morphine seizures occurred in the south, west and eastern regions of the country. This is consistent with likely trans-shipments through Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran on the southern route, as well as the Balkan route, particularly from the western provinces of Afghanistan.

Map 7: Location of heroin seizures in Afghanistan as reported to UNODC and presented in government reports, 2010-2013 Source: UNODC Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS).

Unlike heroin, which is manufactured using tightly controlled chemicals, morphine is much easier to produce with chemicals that are widely available in Afghanistan.

Figure 5: Opium to morphine conversion Source: "Documentation of a heroin manufacturing process in Afghanistan", Federal Criminal Police Office, Wiesbaden, Germany, 2007

Across the region, 2011 and 2012 saw unprecedented seizures in Afghanistan, with significantly higher morphine seizures than in previous years. The reason for the increase is unclear, but it is part of a longer trend of fluctuating seizure data across Afghanistan, Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran. This is also reflected in increased seizures ofopium and heroin from 2011 to 2013, as discussed above and later on in this report.

Since 2010, morphine seizures in Afghanistan have taken place largely in the remote border regions of the provinces of Helmand, Kandahar and Nangarhar. Information about the intended destinations of the consignments is not available, but the location of the seizures could indicate trans-shipment through to the Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan. Importantly, there is a gap in current information on the final use of morphine trafficked from Afghanistan |29|, especially given that it does not have a large user base worldwide. It is possible that, in a similar fashion to opium, it is further processed in a transit location before distribution to consumer markets as heroin.

Figure 6: Morphine seizures in South-West Asia, 2004-2013 (kg) Source: UNODC Annual Report Questionnaire (ARO) and Database on Estimates and Long-term Trend Analysis (DELTA).

It is interesting to note that in Pakistan, morphine seizures have only been reported in Balochistan, located near the Afghan and Iranian borders. However, in the Islamic Republic of Iran, the locations of morphine seizure reports have been more scattered, primarily near its borders with Pakistan, Afghanistan, Turkey and Iraq. Furthermore, for the first time in 2011 morphine seizures were reported along the coastline of Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran. Morphine seizures reported in the Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan also seem to correlate with anecdotal reports of morphine-to-heroin processing outside Afghanistan. In 2008, for example, the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran reported that morphine trafficked via Pakistan had been transferred to Oazvin, in north-west Iran, for conversion at a dairy farm. |30|

Map 8: Location of morphine seizures in Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran as reported to UNODC and presented in government reports and the media, 2010-2013 Source: UNODC Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS)

2.4 Acetic anhydride trafficking

The transformation of morphine into heroin requires the use of the precursor chemical acetic anhydride. Morphine is plentiful in Afghanistan but since there is no licit requirement for acetic anhydride in Afghanistan, it must be procured outside the country from its producers in Europe, South Asia and East Asia among other regions. Afghan heroin production is thus indirectly dependent on diversion of acetic anhydride manufactured legally by the chemical sector worldwide.

Figure 7: Process to convert opium to heroin Note: *oven - dried values are used in estimation; **For the purpose of comparability, 100% pure heroin base is considered.

Source: Afghanistan Opium Survey 2014. UNODC and Afghanistan Ministry of Counter Narcotics, p. 38To reach Afghanistan, acetic anhydride shipments must pass through one of the neighbouring states of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Pakistan or the Central Asian countries to the north. As recently as 2008, virtually all acetic anhydride was brought into Afghanistan without being seized. Since then, significant seizures have been reported, with seizures totalling approximately 41,000 litres in 2012.

Figure 8: Acetic anhydride seizures in Afghanistan, 2004-2013 Source: CNPA

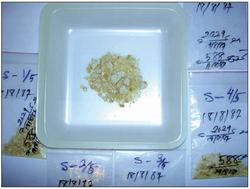

There is also evidence that Afghan heroin is adulterated by manufacturers and/or by traffickers, wholesalers and retailers. The practice of cutting heroin has been previously reported in Afghanistan but it was not until the establishment of a dedicated forensic team within Kabul's CNPA in 2008 that adulterants could be properly identified. Commonly used adulterants identified in 2008-2012 |31| seizures |32| included caffeine, chloroquine (antimalarial medication), |33| phenolphthalein, paracetamoland dextromethorphan. |34|

Figure 9: Chloroquine and Caffeine

Source: UNODC Country Office Afghanistan

Producers may be offsetting the relatively high prices of key precursors such as acetic anhydride |35| by using adulterants, therefore increasing the value of the final product. By adulterating heroin, producers are able to keep prices stable and maintain their profit margin.

In 2011, a random sample of 300 powdered drug submissions was tested at the CNPA laboratory in Kabul. Most samples consisted of low purity heroin with numerous cutting agents identified and only 34 samples (11.33 per cent) could be regarded as reasonably pure heroin. |36| Disaggregating adulterants by countries bordering Afghanistan would likely provide even more discernible insight. Unfortunately, the composition and quality of the various forms of heroin available in Pakistan, the Islamic Republic of Iran and some Central Asian countries remain unknown.

Afghan heroin is brought to drug users worldwide via three main trafficking routes out of Afghanistan: the Balkan route, the northern route and the southern route. |37| The gateway to these routes is through the long and remote borders of Afghanistan, about 2,430 km with Pakistan, 2,230 km with Central Asia and 1,923 km with the Islamic Republic of Iran. Within Afghanistan, the western provinces have been the primary locations for heroin seizures in recent years, until 2013 when the southern provinces (bordering Pakistan) registered higher volumes.

Figure 10: Regional heroin seizures inAfghanistan, 2009-2014 Source: CNPA (until June 2014).

One potential factor explaining this western dominance may be the dual role of Nimroz, a remote province which borders both Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran, thus serving as a conduit for flows into both the Balkan and southern routes.

Figure 11: Annual heroin seizures in Afghanistan, 2009-2014 (June) Source: CNPA (until June 2014)

The overwhelming majority of Afghan opiates are trafficked into the Islamic Republic of Iran, Pakistan or Central Asia. Considering the Afghan provinces of most relevance to the southern route, |38| there are four official border crossings with border control facilities along these borders. These crossings are the Zaranj-Nimroz border crossing (Nimroz province) to the Sistan-Baluchistan province of the Islamic Republic of Iran,the Ghulam Khan border crossing (Khost province) with Pakistan, the Torkham border crossing (Nangarhar province) with Pakistan, and the Wesh-Chaman border crossing (Kandahar province) with Pakistan. In addition to these, there are hundreds of natural passes and desert roads coursing across the entire border, most of which are unmanned and unsupervised.

Map 9: Road network and border control points in east, south and south-west Afghanistan Source: UNODC, The Global Afghan Opium Trade: a threat assessment, 2011, p.34.

Although large one-ton seizures were reported in 2009-2011 in heroin producing provinces like Helmand, only one seizure above 500 kg was reported during 2012-2013. It is noteworthy that, during this same period, much larger seizures were reported outside of Afghanistan, notably in the Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan, as outlined in the relevant chapters. The diversification of supply locations inside Afghanistan has made it difficult to extrapolate routes directly and solely from heroin production areas. |39| However, it would seem peculiar if heroin produced in southern Helmand or eastern Nangarhar were directed anywhere but across the border into Pakistan. Although producing most of the world's heroin, Afghanistan ranks fifth for quantity of heroin seized worldwide.

Figure 12: Top ten heroin seizing countries in the world, 2012 Source: UNODC Annual Report Questionnaire (ARO) and Database on Estimates and Long-term Trend Analysis (DELTA).

The Balkan route has traditionally been the primary route for trafficking heroin out of Afghanistan. |40| However, there are signs of a changing trend, with the southern route encroaching, including to supply some European markets. As mentioned, it is not always possible to categorise movements as either southern or Balkan route until further along in the supply chain. |41| Indeed, heroin trafficked from south-western Afghanistan into the Islamic Republic of Iran could be diverted north through Turkey via the Balkan route or south towards the Middle East and Gulf countries along the southern route. Unlike the northern or Balkan routes that are mostly dedicated to supplying single destination markets - The Russian Federation and Europe respectively - the southern route serves a number of diverse destinations, primarily Western and Central Europe, Africa and Asia and, to a lesser extent, North America. |42| It therefore seems more accurate to talk about a vast network of routes rather than one general flow with the same direction. By examining each node in this network, it is possible to draw a clearer picture of the dynamics and trends in heroin trafficking along this emerging supply route.

Afghanistan is first and foremost important for the southern route as the basic foundation of heroin supply. However, it is difficult to predict in detail how changes to production sites and trafficking networks in Afghanistan may impact the dynamics along the southern route. There would appear to be trade-offs between use of the Balkan route and use of the southern route. Some of these trade-offs are likely influenced by decisions made in Afghanistan. However, the extent to which producers in Afghanistan respond to demands from traffickers just across the border, as opposed to demands from wholesalers and traffickers in more distant locations, is not clear. As this report and its recommendations reflect, the Afghan domestic counter-narcotics challenge is an international concern. Afghanistan has recognised the benefits that come from cooperation with neighbouring countries in particular. The most important of these on the southern route are the Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan, covered in the next two chapters.

3. Pakistan

Pakistan has the sixth largest population in the world |43|, over 2,400 km of border with Afghanistan, and bears the brunt of large-scale heroin trafficking on the southern route. It is among the most significant countries for analysis of opiate trafficking on the southern route and would be a primary partner for anyone interested in reducing the scale and damage caused by Afghan heroin trafficking networks. This chapter begins by addressing flows into and through Pakistan, then studies its own heroin market, before analysing the flows that leave the country.

3.1 Flows into and through Pakistan

The latest estimates by UNODC (2009) would suggest that some 45 per cent of illicit Afghan opiates are trafficked through Pakistan. |44| The overwhelming majority of this is in transit to global markets, while a minority is consumed by opiate users in Pakistan, as detailed below. With the relatively small exception of trafficking through northern Pakistan to China, almost all trafficking through Pakistan occurs along the southern route. However, it is important to differentiate Pakistan as a country from the southern route as a transnational trafficking route passing through numerous countries (including Pakistan). From the traffickers' point of view, it does not matter what land, roads and ports are to the south of Afghanistan - they are simply useful points of transit.

Pakistan's geographical proximity to Afghanistan makes it one of the most significant countries for analysing opiate trafficking on the southern route. The analysis included in this report has significantly benefitted from the data submitted by Pakistan and the country represents a good example of data on drug markets being made available to the international community. On the southern route, Pakistan is one of the few countries that openly and regularly reports data to UNODC on individual drug seizures that provide detailed information on the dynamics of significant seizures and allow the identification of trafficking routes. Pakistan also regularly submits to UNODC (through its responses to the Annual Report Questionnaire) wide-ranging information on drug seizures, modes of transportation, prices of illicit drugs in the country along with information on broad drug trafficking routes to and from Pakistan. Pakistan is also among the few countries in the region that have recently conducted a population-based drug use survey making available accurate data on drug use in the country. The physical and human geography across the opium producing areas of Afghanistan and transit routes through Pakistan provides a broad, deep canvas on which traffickers can operate. There are only three official border crossing points - two are located in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and the other in Balochistan province. The topography of the border areas includes numerous mountain ranges, whose natural passes, trails and desert roads provide likely smuggling routes. Most of these passes, trails and roads are unmanned and as a result, the movement of people crossing the border areas remains largely unchecked. This represents a challenge to the efforts to prevent the overall movement of heroin through these areas, although the recent increase in seizures in the country would suggest a significant increase in law enforcement effectiveness.

Heroin seizures in Pakistan increased by more than 550 per cent between 2008 and 2012, going from 1,900 kg to 12,630 kg. This trend is driven by a combination of larger flows and greater law enforcement activity. This is all the more impressive given active insurgencies in Afghanistan, FATA and Balochistan, which have required the attention of law enforcement agencies.

As Figure 13 shows, the volume of heroin seizures in Pakistan has grown faster than the growth in global seizures overall. In 2013, Pakistan made almost 16.6 per cent of the world's heroin seizures.

Figure 13: Heroin seizures in Pakistan, by volume and quantity of global seizures, 2004-2013 Source: UNODC Annual Report Questionnaire (ARO) and Database on Estimates and Long-term Trend Analysis (DELTA)

Among the many consequences of its proximity to opium production in Afghanistan, Pakistan seizes a variety of opiates. For most countries on the southern route, analysis of opiate trafficking mostly entails analysing heroin trafficking and heroin consumption. In Pakistan, however, traffickers handle opium, morphine and heroin of various grades. Users seem to consume various forms of opiates, a diversity resulting in a more complex picture of the trade.

Figure 14: Southern Afghan border with Pakistan

Source: UNODC

As shown in Figure 15 and in Map 10, heroin has been interdicted in a number of locations, with some notable patterns. The largest collection of seizures occurred along the central border that Balochistan province holds with Afghanistan, down towards the coast near the port of Gwadar. There is no official border crossing near that section of the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, so traffickers have either brought heroin across at the official border crossing to the north-east (Weish-Chaman) and have been repeatedly interdicted travelling westwards towards the Islamic Republic of Iran, or they have taken advantage of a long, remote and porous border to come directly across from neighbouring areas of Afghanistan. Information from Pakistani authorities suggests that the Latter explanation is more common |45|, highlighting that freedom of movement is valuable to traffickers. For Pakistani officials, traffickers expecting non-detection can pose a threat when confronted; the Anti-Narcotics Forces (ANF) lost seven men in counter-narcotics operations in 2012, all serving in Ouetta, the provincial capital of Balochistan. |46|

Figure 15: Reported heroin seizures by provinces/regions in Pakistan, 2010-2013 (% of total in kg) Source: UNODC Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS)

Map 10 also indicates a cluster of seizures around Ouetta, which is likely a combination of heroin collected in Ouetta for redistribution among global supply options (and local demand), and individual shipments in transit from Weish-Chaman through Ouetta and directed further southwards.

Map 10: Location of heroin seizures in Pakistan as reported to UNODC, presented in government reports, 2010-2013 Source: UNODC Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS)

Figure 16 and Map 11 show opium seizures made in Pakistan in recent years, |47| totalling 29,481 kg in 2012. Opium cultivation used to occur in parts of north-western Pakistan, |48| but these were subject to strenuous efforts by the Pakistani counter-narcotics forces, which appear to have been largely successful. Residual production is unlikely to be sufficient even to supply the volume of opium being seized. Compared to heroin seizures, the volume of opium seizures is even more strongly skewed towards Balochistan and the routes heading south and west from the southern border of Afghanistan - accounting for 96 per cent of seizures by volume - although numerous seizures have also been made in Punjab, FATA and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP).

Figure 16: Opium seizures in Pakistan, 2004-2013 (kg) Source: UNODC Annual Report Questionnaire (ARO) and Database on Estimates and Long-term Trend Analysis (DELTA)

Map 11: Location of opium seizures in Pakistan as reported to UNODC and presented in government reports, 2010-2013 Source: UNODC Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS)

Table 2: Number of opium seizures and proportion of opium seized in Pakistan by province, 2010-2013

Province/Region/Territory Distribution (%) of no. of seizures Distribution (%) of total amount (kg) Balochistan 37 96 Sindh 6 1.3 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 15 1.2 Punjab 27 1.2 Islamabad 11 0.2 Federally Administered Tribal Areas 3 0.1 Gilgit-Baltistan 1 0.01 TOTAL 100 100 Source: UNODC Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS)

The movement of opium from Afghanistan into Pakistan suggests at least three possibilities. First, it could point to significant opium markets in Pakistan, in neighbouring countries or more distant regions. As detailed further below, a survey carried out in 2012 estimated that there were 320,000 opium users in Pakistan in 2012, |49| indicating that this is at least part of the explanation. However, given the concentration of seizures in Balochistan, domestic demand would not seem sufficient to absorb the large quantities of opium that appear to be smuggled from Afghanistan into Pakistan.

Secondly, the presence of sizeable quantities of opium could indicate that processing is taking place along the southern route.

Thirdly, opium seizures - particularly those in Balochistan - may indicate that opium consumption in the Islamic Republic of Iran and/or opiate processing along the Balkan route are the magnets for these shipments. This possibility is discussed further in the chapter concerning the Islamic Republic of Iran.

3.1.1 Routes into and through Pakistan

Map 12 summarizes suspected opiate trafficking routes into and through Pakistan,based on seizure data obtained in Pakistan and abroad, as well as information reported by Pakistani authorities |50|. Although only tentatively, the numerous arrows coming over the Afghan border illustrate the challenge facing Pakistan. However, little is known about the multiplicity of routes through Pakistan itself, beyond the fact that many routes terminate at seaports and airports - with the important exception of those traversing Balochistan and heading over the border to the Islamic Republic of Iran, or possibly departing the coast outside of official ports.

Below, the analysis returns to modes and intentions of trafficking through Pakistan, but first it is important to examine consumption in Pakistan itself, which may structure the local opiate trade and help to understand export patterns.

Map 12: Indicative opiate trafficking routes into and through Pakistan prior to 2011 Source: The Global Afghan Opium Trade: A Threat Assessment, UNODC, 2011 based on seizure datafrom Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP), Individual Drug Seizures (iDS) and Annual Report Questionnaires (ARO), supplemented by national government reports and other official reports

Some of the opiates trafficked into Pakistan are consumed there. An estimate based on a survey carried out in 2012 suggested that a Little under 1.06 million people are opiates users - 860,000 heroin users and 320,000 opium users - and that they showed high levels of drug dependence. |51| The highest prevalence of users was found in Balochistan (1.6 per cent of the provincial population). There appears to be a correlation between prevalence rates and major trafficking routes through Pakistan, suggesting that a share of the opiates trafficked along the southern route supply domestic markets along the route.

When combining information from Pakistani authorities |52| with data on opiates seized elsewhere that departed from Pakistan, some interesting patterns emerge. From a geographical standpoint, opiates trafficked by sea out of Pakistan must be dispatched from the coasts of Balochistan and Sindh provinces. In regards to seizures made at seaports or the immediate vicinity, 15 seizures alone accounted for 2,419 kg of heroin. Maritime trafficking out of Pakistan presents opportunities for traffickers to quickly move large quantities of heroin - or opium - to third countries.

By contrast, for trafficking by air, if traffickers want to reduce risks by hiding opiate couriers or parcels among passengers and cargo of commercialflights, they have opportunities to do so using the busier air routes, which would mean favouring departures from Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar and Islamabad. All these cities have multiple connections to the Middle East, with Karachi and Lahore also offering several connections to South and South-East Asia, as well as Europe. As described below, air trafficking relies to a greater extent on numerous small shipments to mitigate risk of detection.

When examining seizure data for evidence on the most popular export routes out of Pakistan, one of the challenges encountered is that most seizures are reported without details on the intended points of departure from Pakistan. For instance, if a seizure is made in Punjab from a car in the open air, the mode of trafficking will usually be reported as 'land'. What is generally unknown is whether it was intended to leave Pakistan via, for example, Karachi seaport, Lahore airport, across the Iranian border or by mail.

In FATA and the Gilgit-Baltistan region, all seizures reported to UNODC |53| show land as the mode of trafficking, which is not surprising. In Balochistan province, the vast majority of heroin seizures, by number and by weight, also occur on land. On the one hand, this is not surprising, given its limited air connections |54| and the large flows of heroin likely to be trafficked across the province using vehicles. |55| The largest seizures in Pakistan are typically reported in Balochistan, near the border with Afghanistan. The ANF recorded the largest seizure in its history in this area, seizing 1,096 kg of heroin from a house in the Chagai district in January 2013, |56| reportedly destined for the Islamic Republic of Iran. It is, however, surprising that there have been few interdictions of heroin trafficked by sea, despite Balochistan's ample coastline and data provided by other countries. |57| In fact, for several years there have been reports of heroin trafficking via the coastal areas of Balochistan. |58| As suggested by the ANF, "the coastal areas of Pakistan (Karachi, Port Oasim and the small fishing ports along the Makran coast) are also vulnerable to drug smuggling activities towards Gulf States and beyond". |59|

Table 3: Weekly schedule of International Flight Operations from Balochistan (Pakistan)

No. Departing from Destination Flights per week 1 Turbat (Makran Division, Balochistan) Sharjah (United Arab Emirates) 03 2 Turbat (Makran Division, Balochistan) Muscat (Oman) 01 3 Gwadar (Makran Division, Balochistan) Muscat (Oman) 01 Source : Pakistan International Airlines

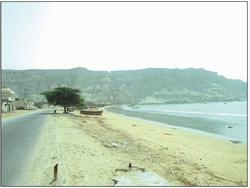

Figure 17: Gwadar beach and Gwadar seaport

Source: UNODC

The data for Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab and Sindh show different patterns. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Land is the dominant mode of trafficking as regards heroin volume, accounting for over three-quarters of seized weight. However, the majority of interdictions were made against attempts to traffic opiates by air. The most plausible explanation is that flows intercepted on land are a mixture of heroin trafficked through Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to depart from other provinces, and bulky cargos that is later broken down into small consignments to be trafficked by air.

A similar situation has prevailed in Punjab, where three-quarters of seizures by volume have occurred on land, but around 40 per cent of seizures by number have been attempts to export heroin using air routes. A difference between Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is the greater prevalence of attempts by mail from Punjab, which accounts for about 20 per cent of cases (see Figure 18).

Figure 18: Modes of trafficking in Punjab. Left: number of cases. Right: Amount of heroin, 2010-2013 Source: UNODC Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS)

Finally, Sindh's experience has been unique. By quantity of heroin seized, the majority has been intended for trafficking by sea, with shipments averaging over 100 kg; that said, these accounted for only 6 per cent of cases. Seizures resulting from trafficking by air consisted of around 10 per cent of the total quantity seized in Sindh, but this is spread over a greater number of attempts - around half of all interdicted attempts. Even more than Punjab, trafficking by mail has featured prominently in the number of seizures in Sindh (around one-third of cases), but makes up only 2 per cent of the quantity seized.

Figure 19: Modes of trafficking in Sindh. Left: number of cases. Right: Amount of heroin 2010-2013 Source: UNODC Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS)

Individual chapters of this report further detail southern route trafficking to other regions. Here, it is important to note that heroin is trafficked out of Pakistan along a vast array of trajectories. Table 4 shows the destinations of heroin seized, known to be transiting Pakistan. Map 13 illustrates some of the known connections and modes oftrafficking that connect the southern route to the rest of the world, via Pakistan.

Table 4: Intended destinations of seized heroin that transited Pakistan, 2010-2013

Destination Number of seizures Amount seized Percentage of total (%) Middle East and Gulf States 34 28 Africa 2 5 Europe 37 37 South Asia 8 5 East and South-East Asia 13 20 North America 4 4 Oceania 2 1 Source: UNODC Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS)

Map 13: Indicative heroin trafficking routes from Pakistan, 2010-2013 Note: The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Sudan and South Sudan has not yet been determined.

Source: UNODC elaboration, based on seizure data from Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) Individual Drug Seizures (IDS) and Annual Report Questionnaire (ARO), supplemented by national government reports and other official reportsIn terms of modes of trafficking, there are some apparent differences between the various regions. For example, seizures of heroin trafficked from Pakistan to South Asia by mail are generally larger than interdicted attempts to mail heroin from Pakistan to Europe. In another example, seizures of heroin intended for trafficking by sea are generally much larger when destined for Africa, Europe and the Middle East than interdicted attempts by air, although these are more frequent.

The existence of drug trafficking connections between Pakistan and Africa is also suggested by the nationalities of those arrested in Pakistan for drug trafficking offences. Although over 90 per cent of these were Pakistani nationals, |60| the remainder originated primarily from Africa - primarily Nigerian and Zambian nationals, with less frequent arrests of people from Ghana, Mali,Tanzania, Mozambique and South Africa. Interdicted trafficking attempts from Pakistan, made outside the country, involved the arrest of at least 100 Pakistani nationals between 2010 and 2013, as well as more than 60 nationals of African countries, primarily Nigerians. |61|

Pakistan faces a tremendous challenge in dealing with the large flows of opiates originating from Afghanistan to feed its heroin market and to supply demand in many other regions of the world. Along with the Islamic Republic of Iran, the geographic location of Pakistan makes it a major transit point for trafficking of Afghan opiates along the southern route. Balochistan witnesses the largest flows but trafficking through other parts of Pakistan for domestic consumption and global export should not be discounted. This is particularly important in relation to exports from Karachi and the numerous consignments that appear to be trafficked by air. Seizures further out in the Indian Ocean have also highlighted the potential for traffickers to send sizeable shipments using boats departing from unofficial ports and jetties along the coast of Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran. Maritime trafficking out of Pakistan seemingly presents opportunities to smuggle large quantities of heroin (or opium) to third countries quickly, while trafficking using air transport would smuggle smaller quantities of drugs per consignment in order to avoid detection.

So long as Afghanistan is a major producer of opiates, Pakistan will struggle to contain transnational trafficking. Recent years have shown that Pakistan has intercepted large volumes of opiates -just under 18 per cent of the global total of heroin seizures in 2012 and 16.5 per cent in 2013. |62| This is to the benefit of countries downstream on the southern route. In the last decade, Pakistan has also considerably developed its international counter-narcotics cooperation; as a frontline state on the southern route, supporting progress in Pakistan in this regard will be critical to ensuring counter-narcotics progress overall.

4. The Islamic Republic of Iran

In 2012, the Islamic Republic of Iran accounted for around 14 per cent of global heroin seizures and about 70 per cent of global opium seizures. |63| In the 1970s, the Islamic Republic of Iran was one of the largest opium producing countries in the world; however, a decade or so later, its opium production ceased. |64| Today, the major anti-narcotics challenges relate to the country's location as a key transit point along the southern and Balkan routes, and to its sizeable domestic drug market.

The country's geography, particularly its 1,923 km-long |65| eastern border with Afghanistan and Pakistan, makes it a major crossroads for the movement of illicit drugs from Afghanistan to other markets. The border between the Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan crosses mountainous and desert terrain, making it extremely difficult for anti-narcotics police and border officials to identify and interdict trafficking ventures in the area.

Islamic Republic of Iran reported that 14 national law enforcement officials have been killed or gone missing in counter-narcotics operations in 2013 alone. |66| Iranian drug law enforcement agencies report an average of four armed clashes with drug traffickers per day. |67| The country has also been implementing a large-scale construction programme involving the erection of barriers and embankments along its borders, with a view to prevent drug trafficking as well as the cross-border movement of other armed groups (see Figure 20). |68|

The impact of the counter-narcotic measures implemented by the Islamic Republic of Iran is illustrated through national price data. Figures for 2012 showsharp increases in price for opium and heroin between common entry and exit points. For example, the price of opium is 400 USD per kg at the eastern border with Afghanistan, but rises to 1,700 USD per kg at the western border with Turkey. For heroin, the price increases from 5,000 USD to 13,500 USD per kg at those same locations. |69| Nevertheless, seizure data suggests that traffickers and individual drug couriers continue to rely on the Islamic Republic of Iran as a key transit point to markets in Europe or elsewhere, and enjoy some success in traversing the country undetected.

Figure 20: Iranian-Afghan border

Source: Drug Control Headquarters the Islamic Republic of Iran

Islamic Republic of Iran also faces a major challenge in terms of domestic use of heroin and opium. The prevalence of opiate use in the country is among the highest in the world, reported at 2.8 per cent in 2009. This number reflects 1.36 million opiate users in the country including about approximately 390,000 heroin users, 530,000 opium users and 440,000 users of other opiates. |70| 15 per cent |71| of people injecting drugs in the Islamic Republic of Iran have HIV, adding further to the threat posed to drug users.

Heroin seizures in the Islamic Republic of Iran increased steadily between 2005 and 2010. |72| However, in 2011 and 2012 the amounts fell by 15 per cent and 56 per cent respectively. In 2009, the Islamic Republic of Iran accounted for 85 per cent of heroin seizures made in the region. This share rose to 75 per cent in 2010, before falling to 55 per cent in 2011 and 34 per cent in 2012. |73|

Figure 21: Heroin seizures in the Islamic Republic of Iran, 2004-2013 Source: UNODC Annual Report Questionnaire (ARO) and database on estimates and long-term trend analysis (DELTA)

Heroin trafficking routes traversing Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran supply two global heroin routes -the Balkan route and the southern route. The Balkan route leads to Europe through Turkey, while traffic on the southern route is diverted through Gulf States to Europe or via maritime routes through Africa, Asia, and Oceania. There also appears to be substantial trafficking by air to multiple destinations around the world (elaborated further in the next chapters).

The use of the southern route to traffic heroin through the Islamic Republic of Iran is not a new occurrence. Research carried out by UNODC |74| in 2002 highlighted the use of the southern route departing from Pakistan (Gwadar port) into the Iranian province of Sistan-Baluchistan (Chabahar port) or continuing through Hormuzgan province (Bandar-Abbas port) all the way to Khuzestan (south-west of the country, bordering the Iraqi province of Basra and the Persian Gulf |75|). The exit points identified at the time were the following:

- Bandar Abbas-United Arab Emirates.

- Iranian sea coast-Kuwait.

- Iranian sea coast-Iraq.

However, a crucial difference is that this route was thought to be used mostly for hashish trafficking. A similar assessment was made of the coastline of Pakistan at the time. |76| It would appear that heroin traffickers have simply made use of pre-existing routes to export opiates out of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Map 14: Indicative heroin trafficking routes through the Islamic Republic of Iran Source: UNODC (2011), The Global Afghan Opium Trade: a threat assessment, p. 40

Historically, Western and Central Europe has been supplied with Afghan heroin almost exclusively through the Balkan route, but there have been reports of declining flows along this route. |77| The strengthening of borders at crucial locations along the route |78| and the successful arrest and conviction of high-level traffickers engaged in the importation and distribution of heroin from the Islamic Republic of Iran through Turkey to Western and Central Europe, may have impacted trafficking along the Balkan route and encouraged some traffickers to seek alternative routes. |79| In addition to the southern route, this could involve bypassing the Turkish-Iranian border altogether by trafficking via the Caucasus |80| or the adjacent Iraqi border. |81|

Distinguishing between heroin trafficking destined for the southern or the Balkan route inside the Islamic Republic of Iran is likely to be difficult. Yet, heroin located in provinces bordering Pakistan, the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman is more likely to be diverted through the southern route, while heroin located further north is more likely to be trafficked via the Balkan route. The specific provinces of relevance for the southern route are Sistan-Baluchistan, Kerman, Hormozgan, Fars, Bushehr, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Khuzestan, Ham, Loristan and Kermanshah. Map 15 shows two broad clusters of seizures, one in the south-east, in provinces primarily related to the southern route and the other further north and towards the west of the country, where heroin is more likely destined to Europe via the Balkan route.

Map 15: Location of heroin seizures in the Islamic Republic of Iran as reported to UNODC, presented in government reports and as reported by the media, 2010-2013 Source: UNODC Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS)