CONTENTS

PREFACE

Since the last Global Report on Trafficking in Persons in 2014 there have been a number of significant developments that reinforce this report's importance, and place it at the heart of international efforts undertaken to combat human trafficking. Perhaps the most worrying development is that the movement of refugees and migrants, the largest seen since World War II, has arguably intensified since 2014. As this crisis has unfolded, and climbed up the global agenda, there has been a corresponding recognition that, within these massive migratory movements, are vulnerable children, women and men who can be easily exploited by smugglers and traffickers.

Other changes are more positive. In September 2015, the world adopted the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and embraced goals and targets on trafficking in persons. These goals call for an end to trafficking and violence against children; as well as the need for measures against human trafficking, and they strive for the elimination of all forms of violence against and exploitation of women and girls. Thanks to the 2030 Agenda, we now have an underpinning for the action needed under the provisions of the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, and its protocols on trafficking in persons and migrant smuggling.

Another important development is the UN Summit for Refugees and Migrants, which produced the groundbreaking New York Declaration. Of the nineteen commitments adopted by countries in the Declaration, three are dedicated to concrete action against the crimes of human trafficking and migrant smuggling. UNODC's report is also the last before the world gathers in 2017 at the UN General Assembly for the essential evaluation of the Global Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons. These decisive steps forward are helping to unite the world and produce much needed international cooperation against trafficking in persons.

But, to have tangible success against the criminals, to sever the money supplies, to entertain joint operations and mutual legal assistance, we must first understand the texture and the shape of this global challenge. The Global Report on Trafficking in Persons does exactly this. It provides a detailed picture of the situation through solid analysis and research. The findings are disturbing.

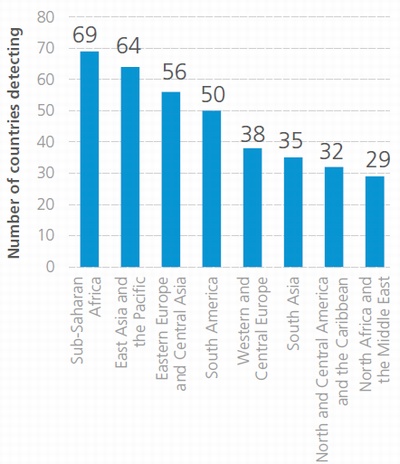

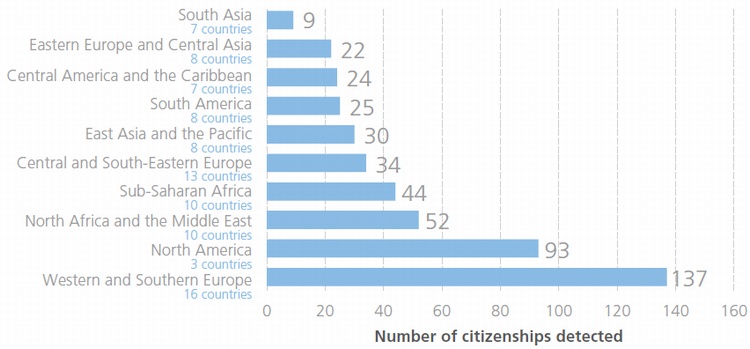

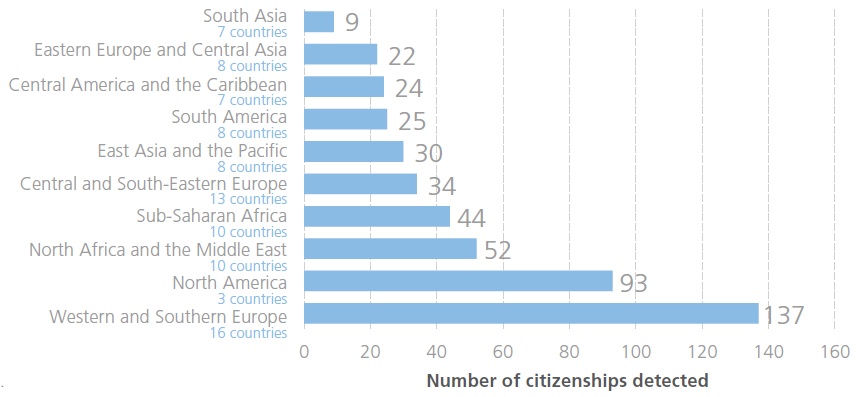

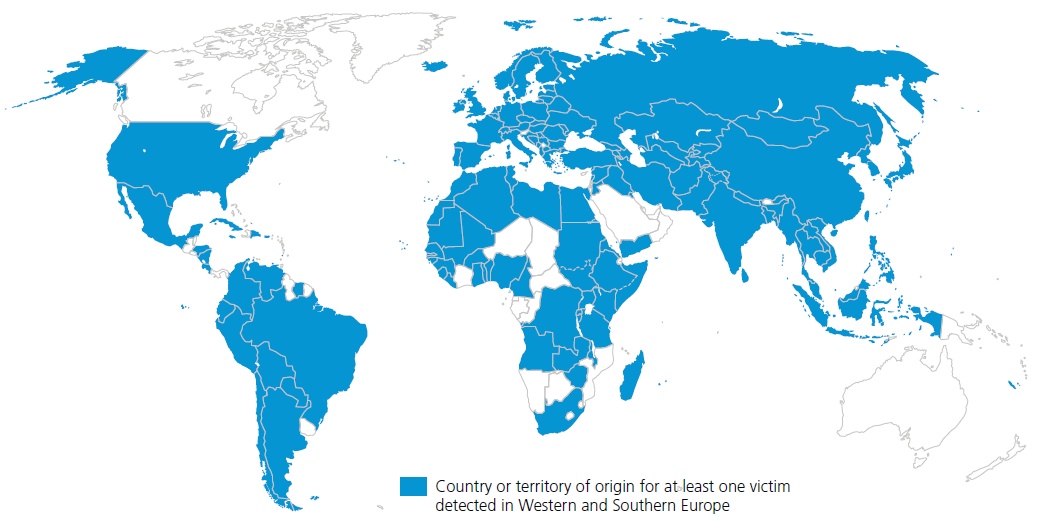

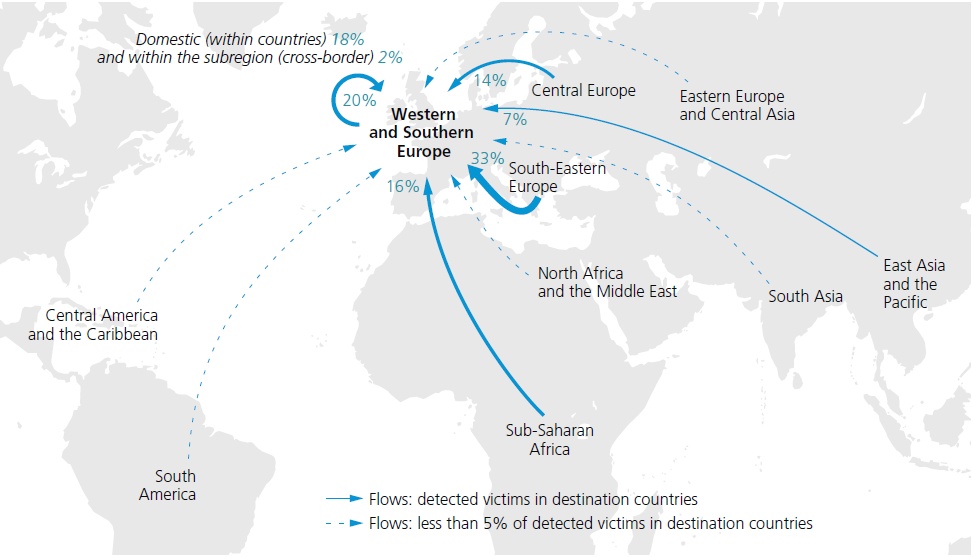

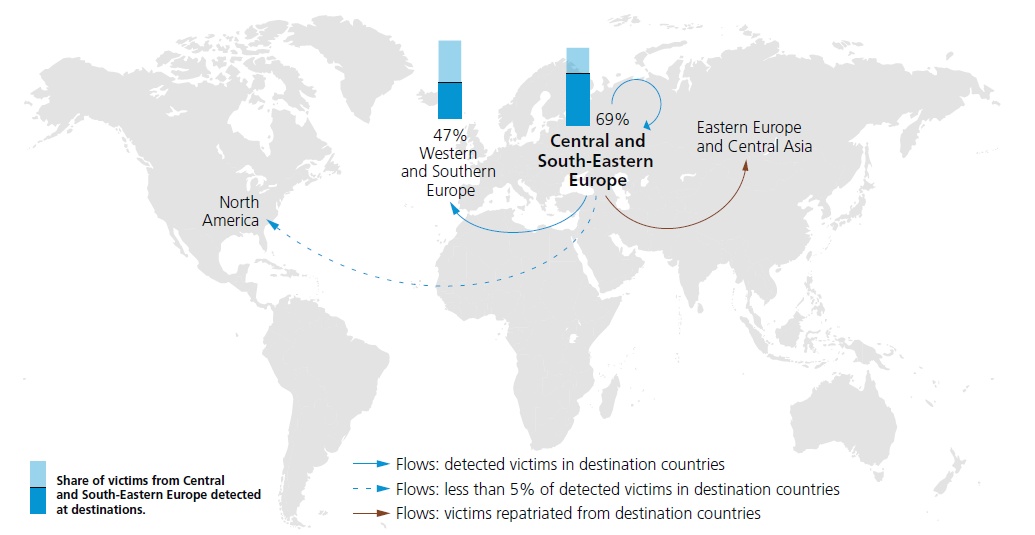

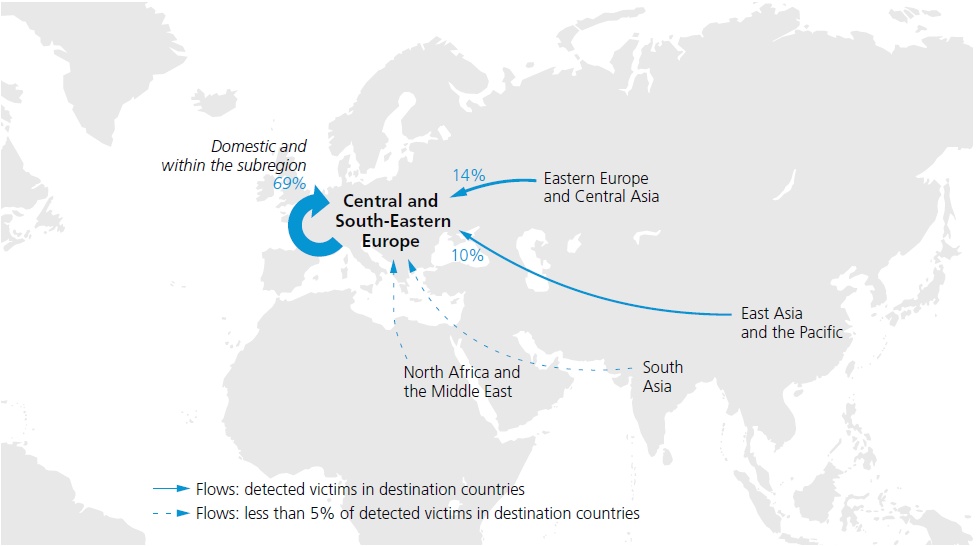

Traffickers may target anyone who can be exploited in their own countries or abroad. When foreigners are trafficked, we know that human trafficking flows broadly follow the migratory patterns. We know from the report that some migrants are more vulnerable than others, such as those from countries with a high level of organized crime or from countries affected by conflicts. Just as tragically, 79 per cent of all detected trafficking victims are women and children. From 2012-2014, more than 500 different trafficking flows were detected and countries in Western and Southern Europe detected victims of 137 different citizenships. These figures recount a worrying story of human trafficking occurring almost everywhere.

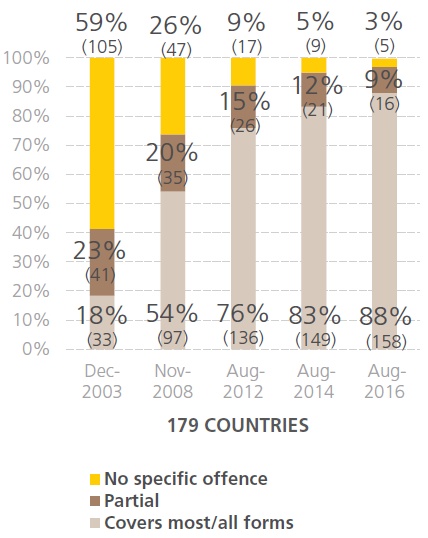

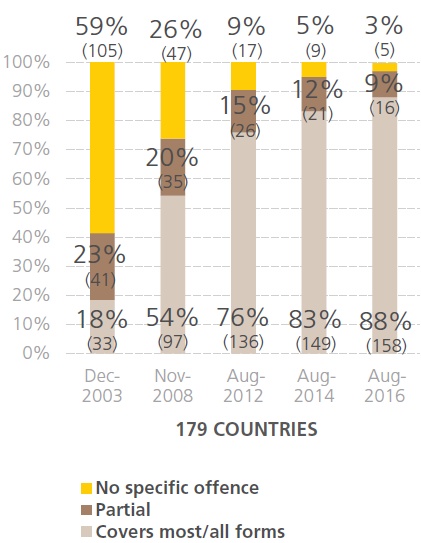

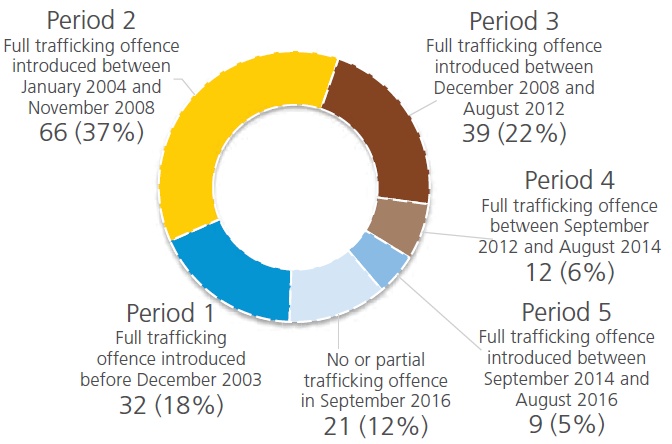

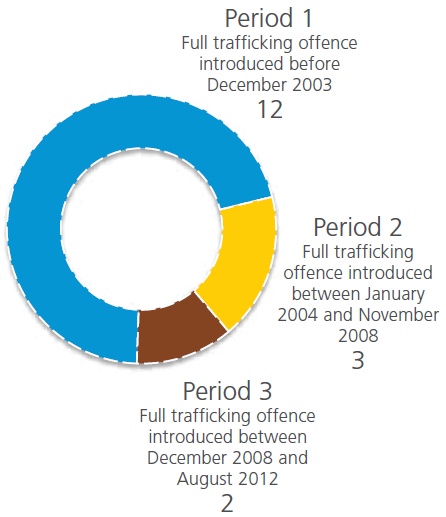

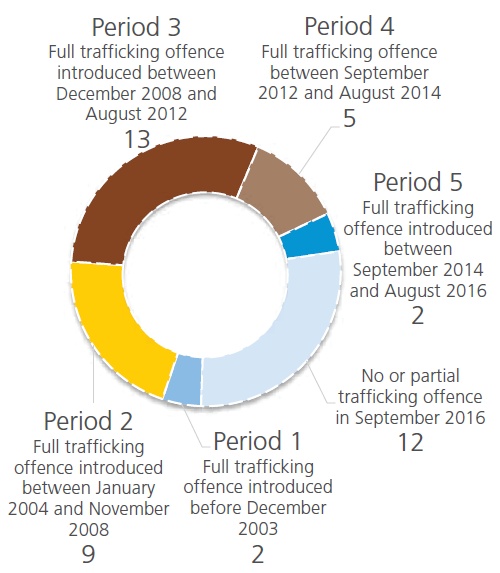

In terms of the different types of trafficking, sexual exploitation and forced labour are the most prominent. But the report shows that trafficking can have numerous other forms including: victims compelled to act as beggars, forced into sham marriages, benefit fraud, pornography production, organ removal, among others. In response, many countries have criminalized most forms of trafficking as set out in the UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol. The number of countries doing this has increased from 33 in 2003 to 158 in 2016. Such an exponential increase is welcomed and it has helped to assist the victims and to prosecute the traffickers.

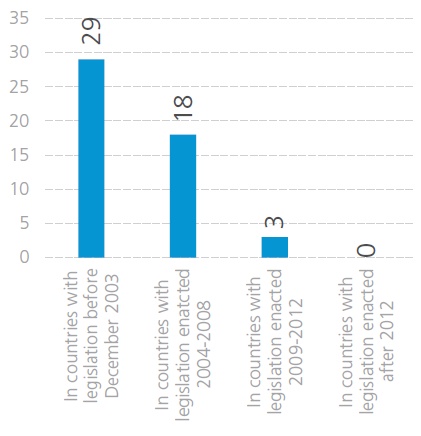

Unfortunately, the average number of convictions remains low. UNODC's findings show that there is a close correlation between the length of time the trafficking law has been on the statute books and the conviction rate. This is a sign that it takes time, as well as resources, and expertise to chase down the criminals. Perhaps the 2016 Report's main message is that inroads have been made into this horrendous crime. We must, however, continue to generate much needed cooperation and collaboration at the international level, and the necessary law enforcement skills at the national and regional levels to detect, investigate and successfully prosecute cases of trafficking in persons. The 2016 report has done a fine job of setting out the situation, but there is more to be done.

Yury Fedotov

Executive Director

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1) NO COUNTRY IS IMMUNE FROM TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS

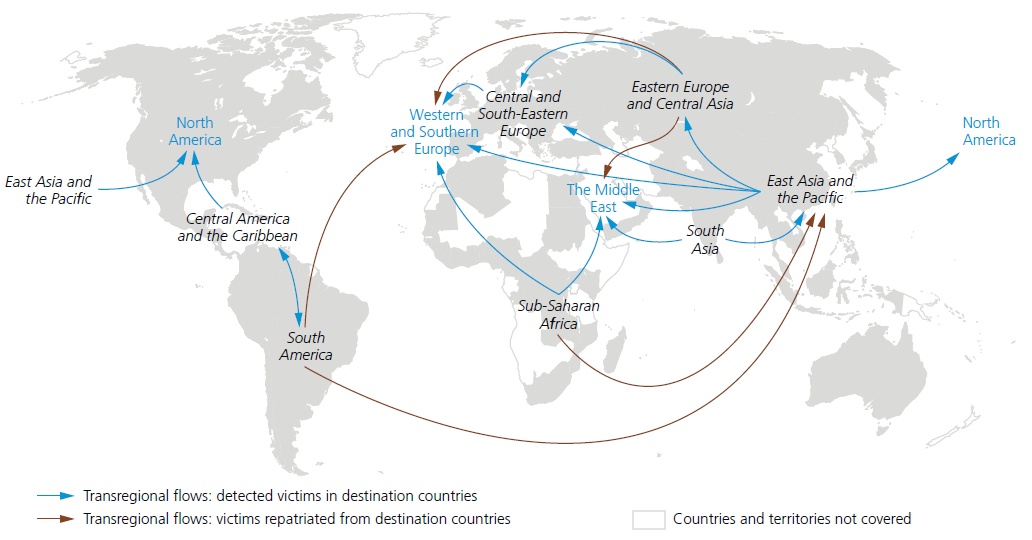

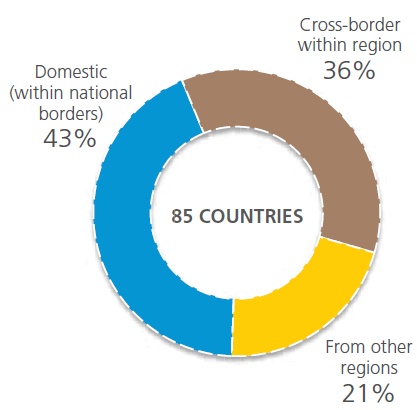

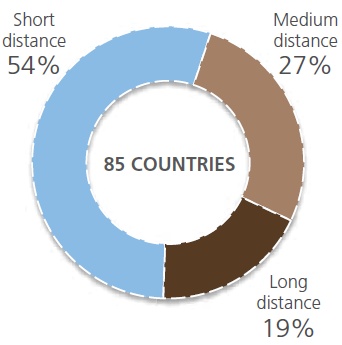

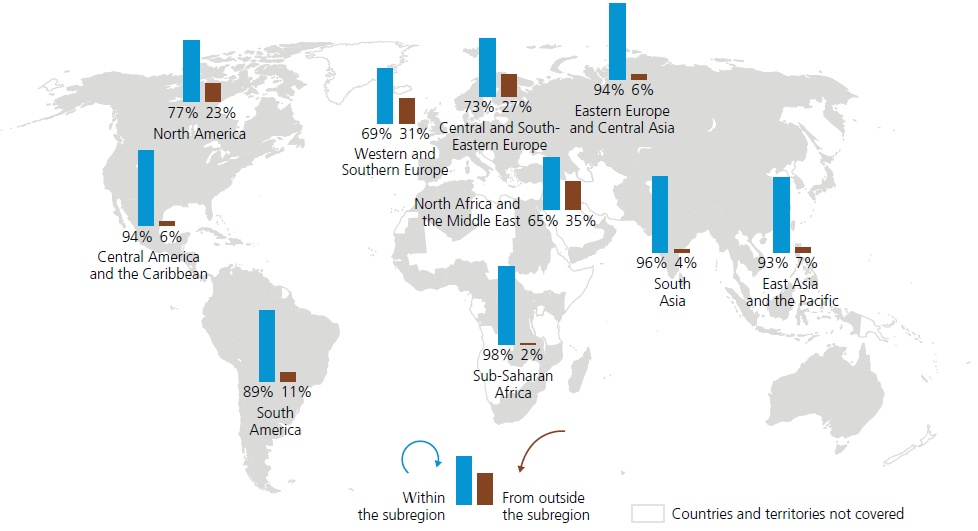

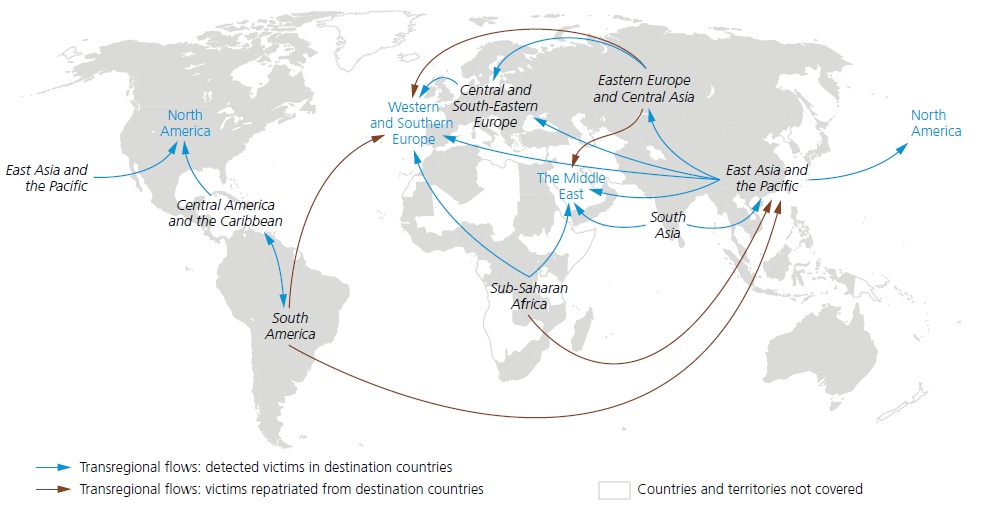

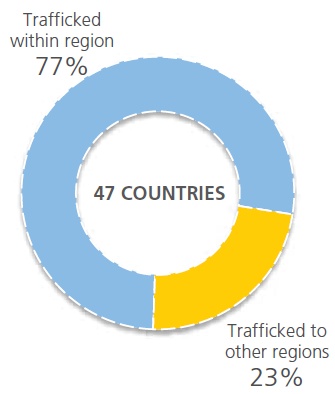

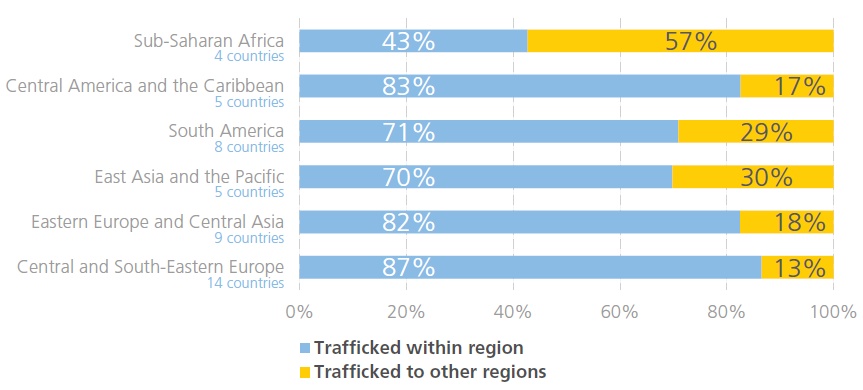

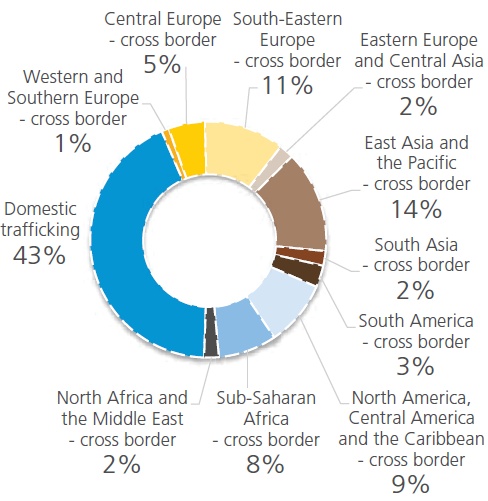

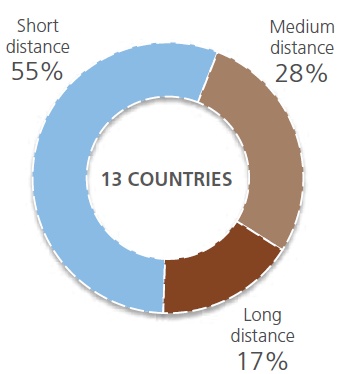

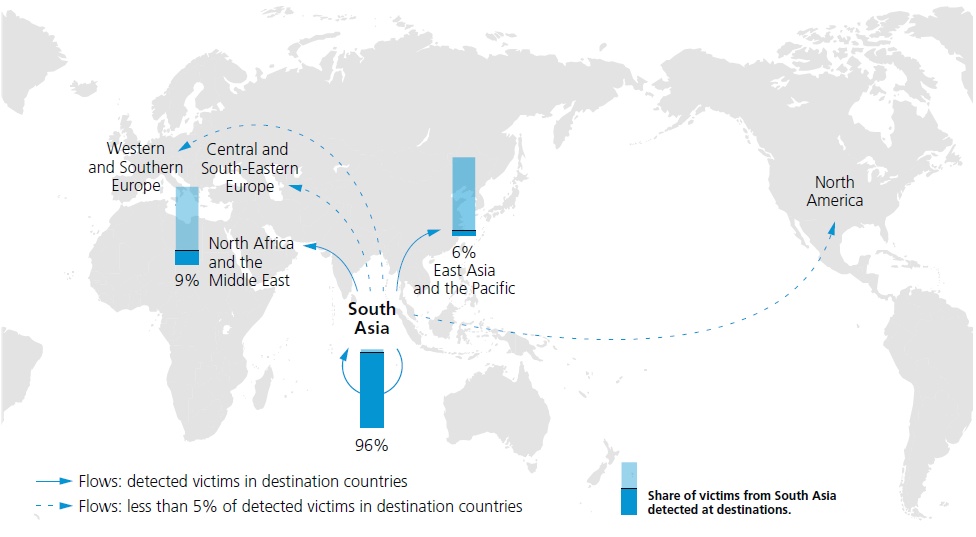

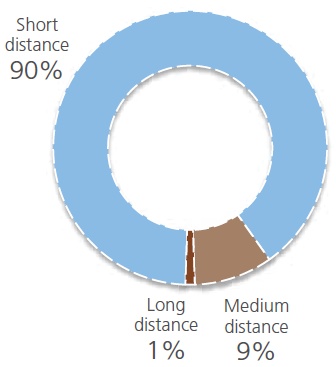

Victims are trafficked along a multitude of trafficking flows; within countries, between neighbouring countries or even across different continents. More than 500 different trafficking flows were detected between 2012 and 2014.

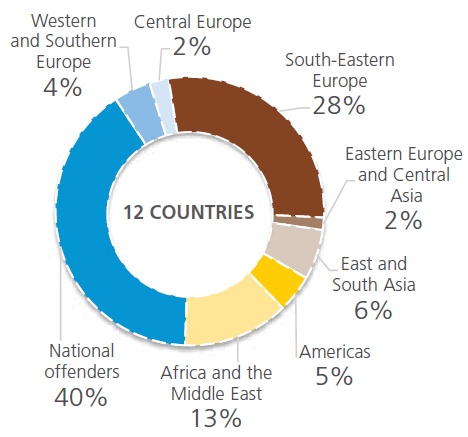

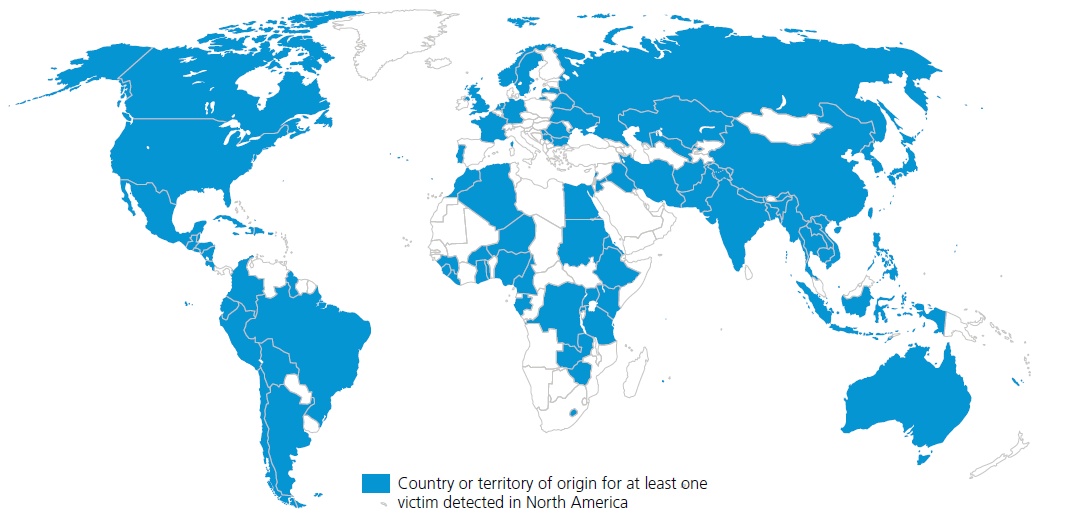

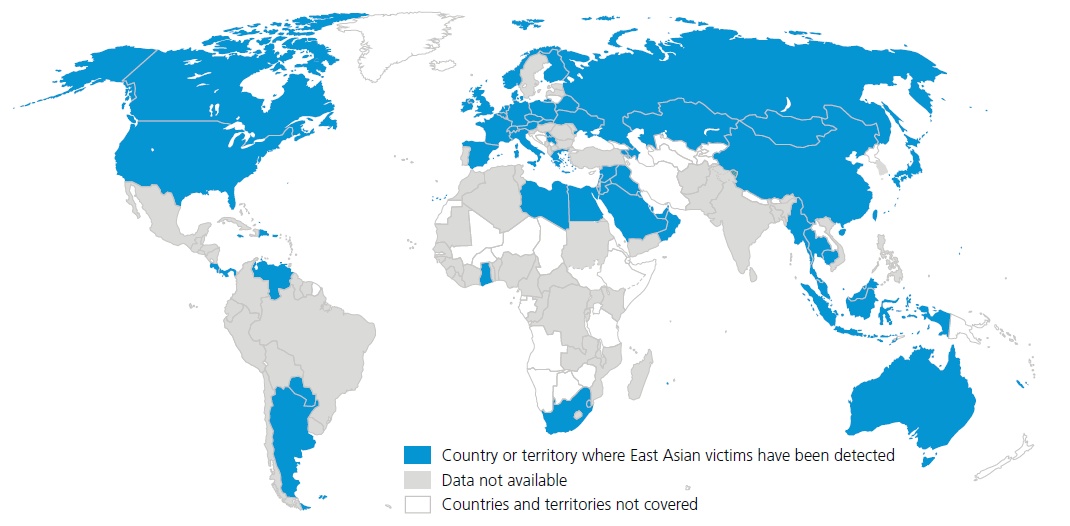

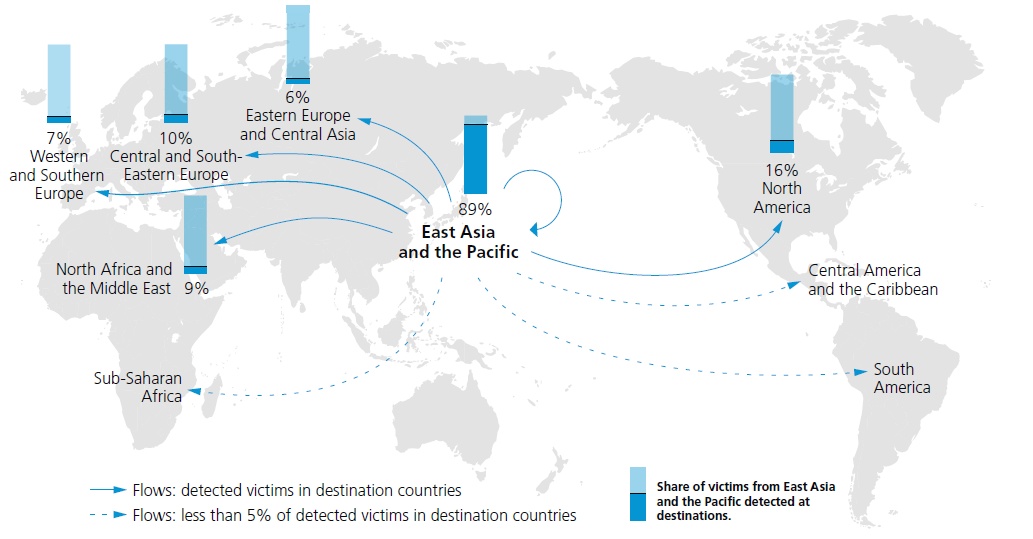

Countries in Western and Southern Europe detected victims of 137 different citizenships. Affluent areas – such as Western and Southern Europe, North America and the Middle East - detect victims from a large number of countries around the world.

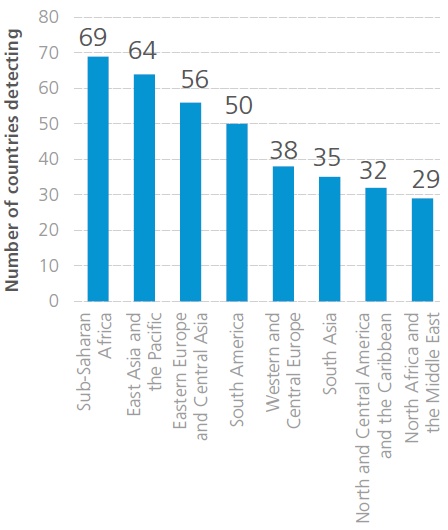

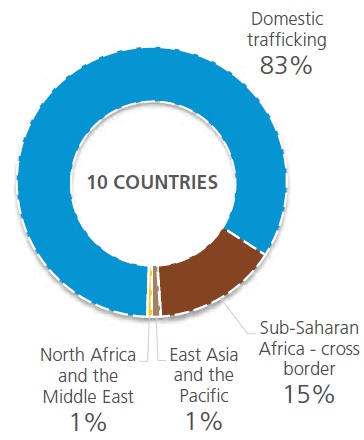

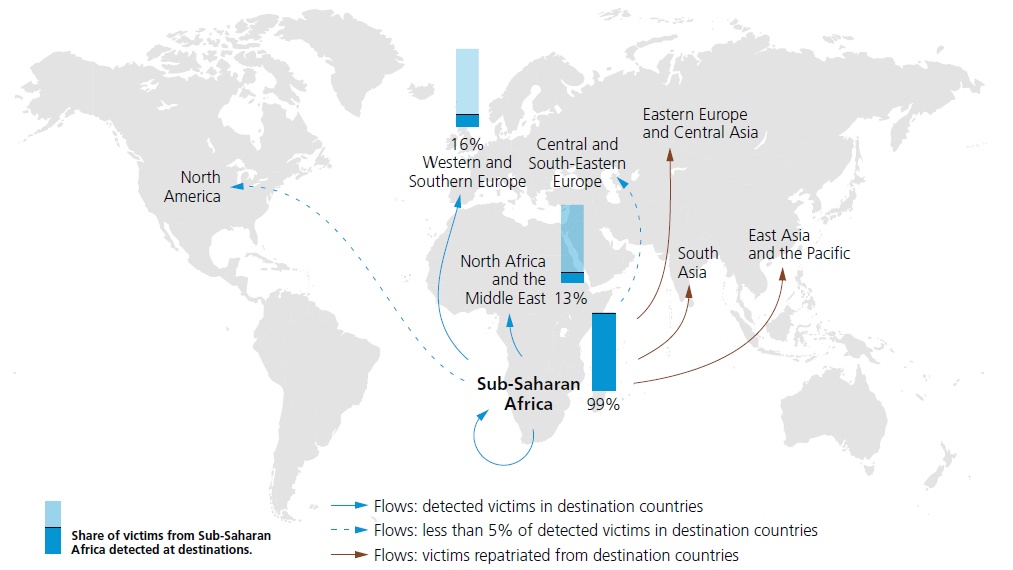

Trafficking victims from countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia are trafficked to a wide range of destinations. A total of 69 countries reported to have detected victims from Sub-Saharan Africa between 2012 and 2014. Victims from Sub-Saharan Africa were mainly detected in Africa, the Middle East and Western and Southern Europe. There are also records of trafficking flows from Africa to South-East Asia and the Americas.

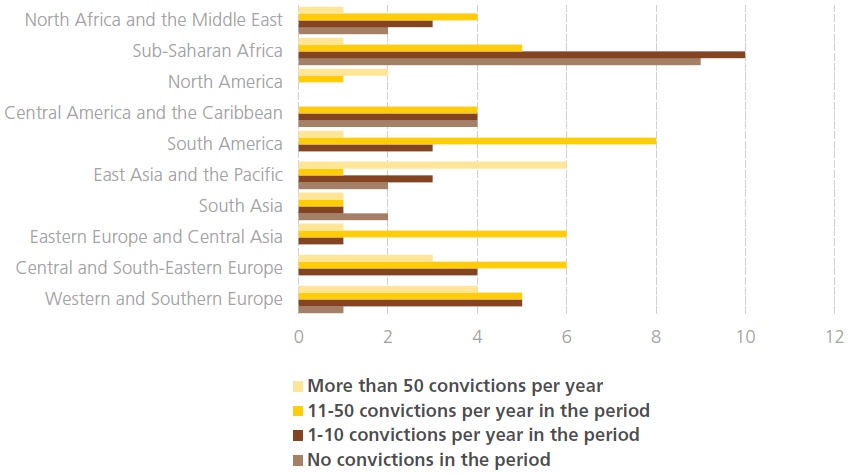

Diffusion of trafficking flows: number of countries where citizens of countries in the given subregions were detected, 2012-2014

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

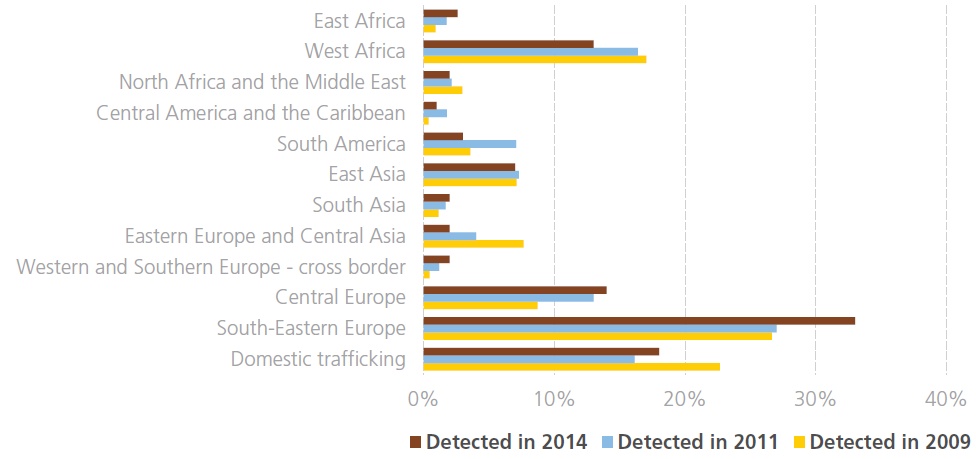

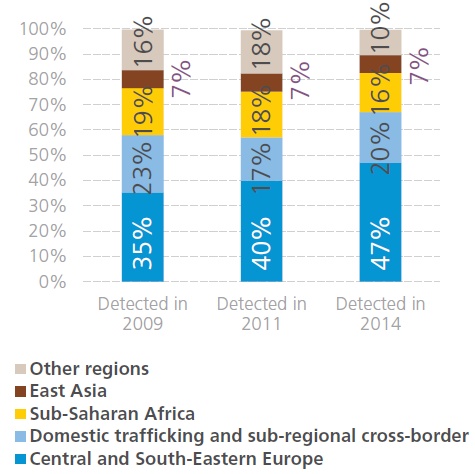

2) HOW HAS TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS CHANGED IN RECENT YEARS?

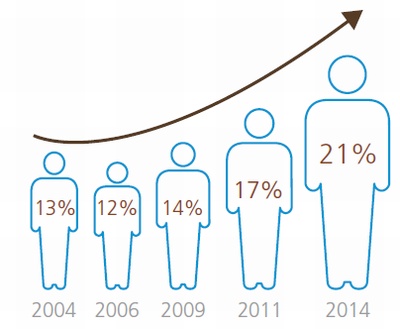

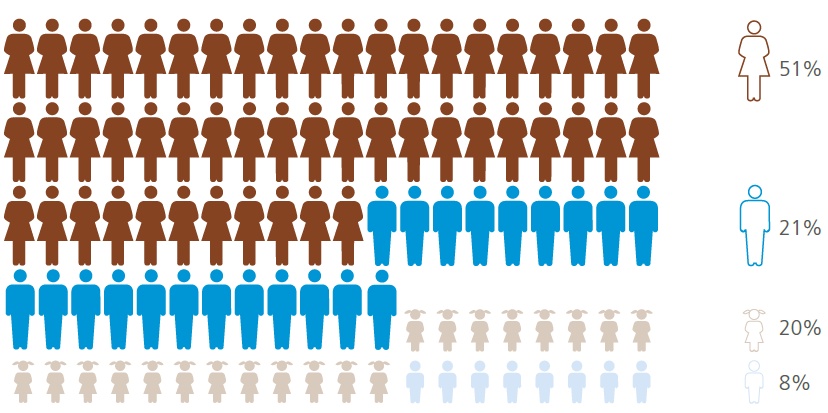

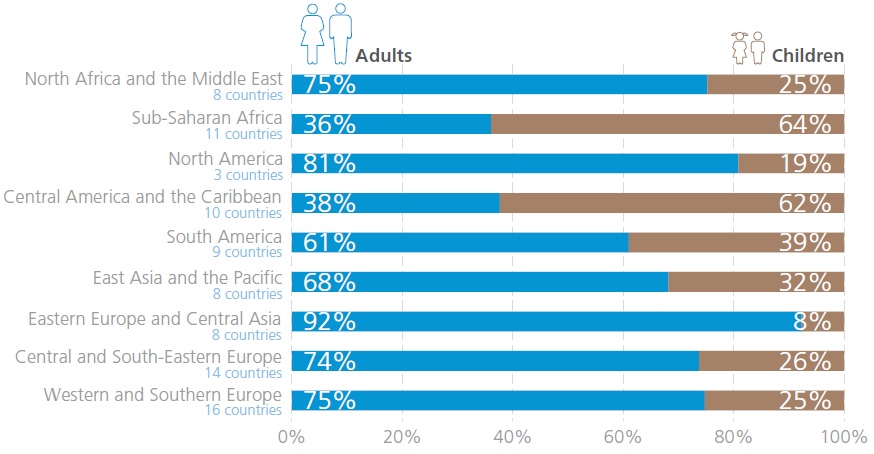

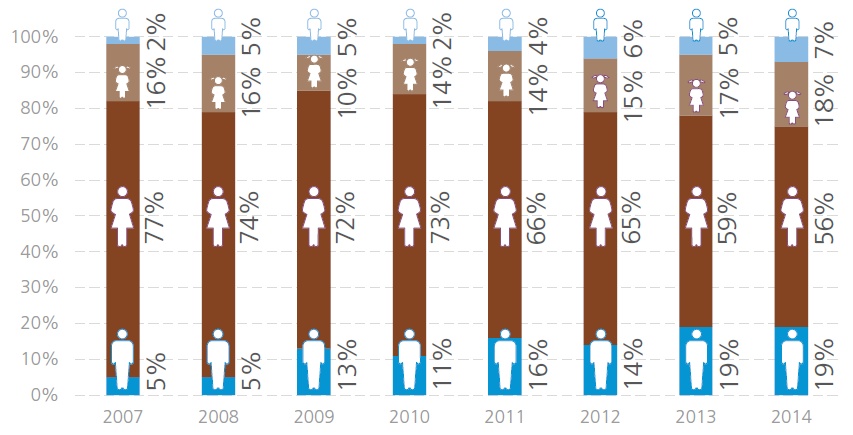

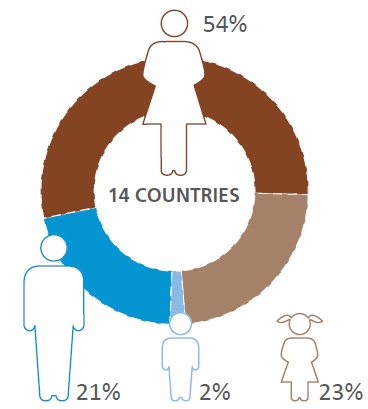

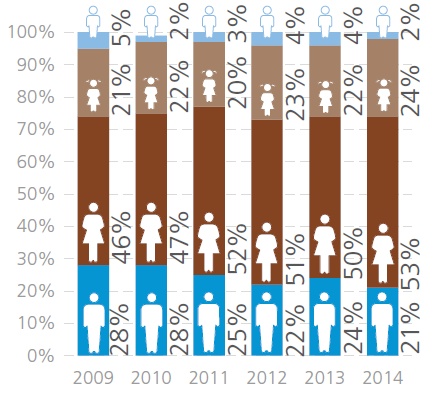

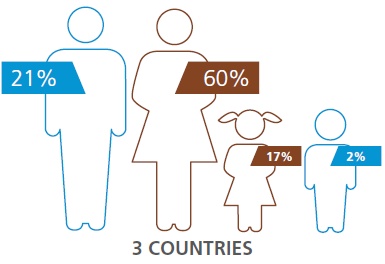

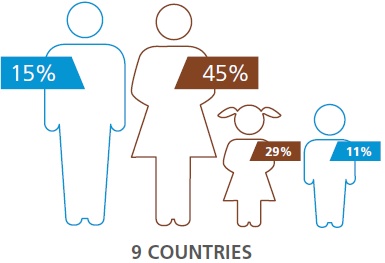

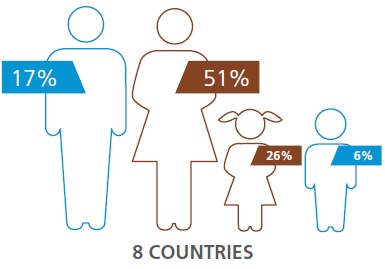

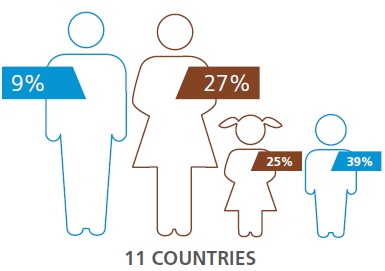

Over the last 10 years, the profile of detected trafficking victims has changed. Although most detected victims are still women, children and men now make up larger shares of the total number of victims than they did a decade ago. In 2014, children comprised 28 per cent of detected victims, and men, 21 per cent.

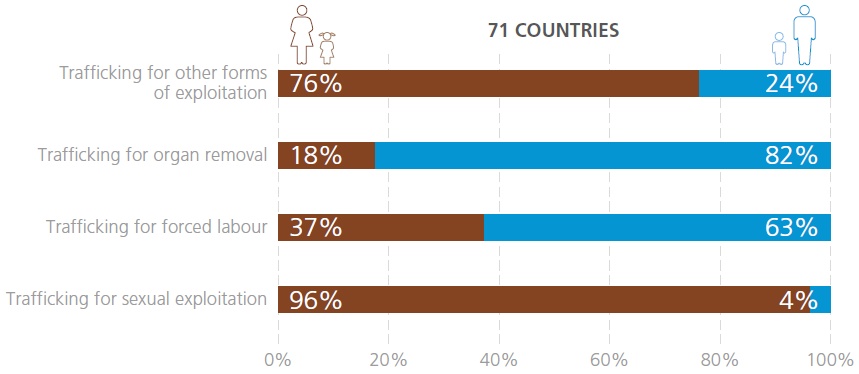

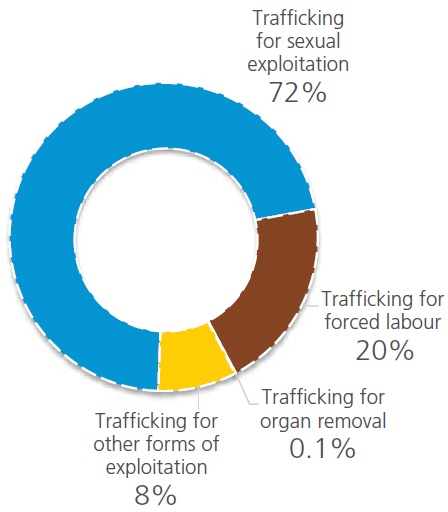

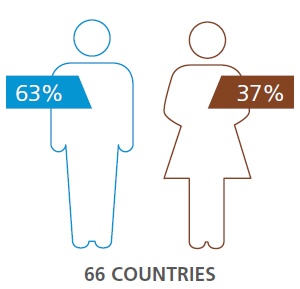

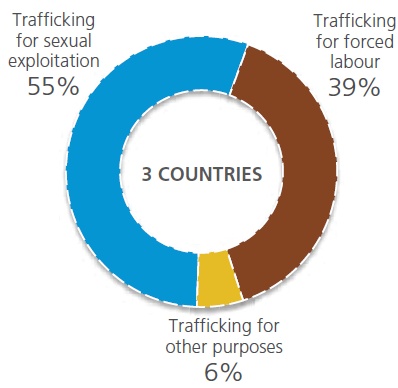

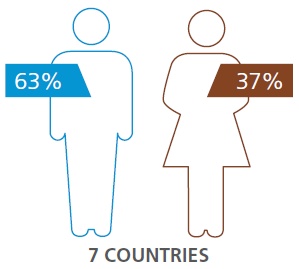

In parallel with the significant increases in the share of men among detected trafficking victims, the share of victims who are trafficked for forced labour has also increased. About four in 10 victims detected between 2012 and 2014 were trafficked for forced labour, and out of these victims, 63 per cent were men.

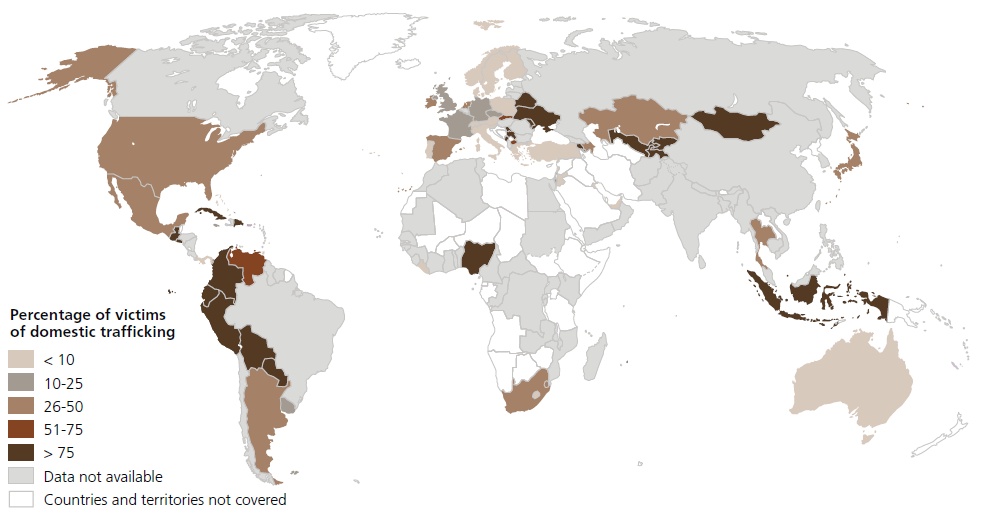

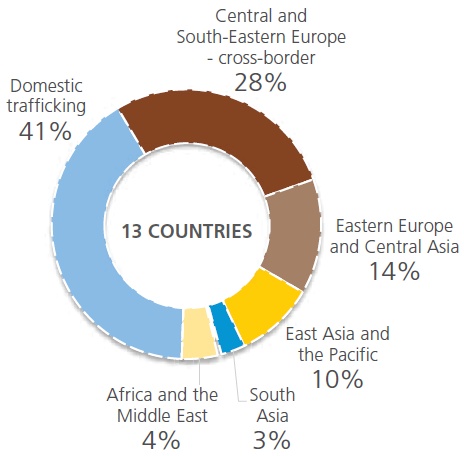

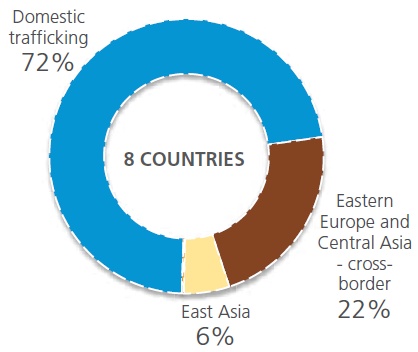

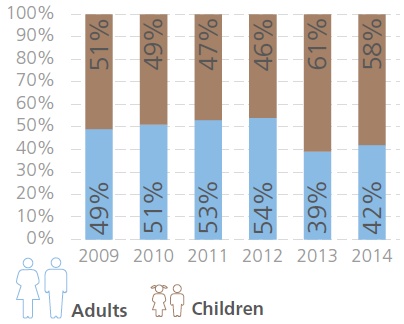

The share of detected trafficking cases that are domestic - that is, carried out within a country's borders – has also increased significantly in recent years, and some 42 per cent of detected victims between 2012 and 2014 were trafficked domestically. While some of the increase can be ascribed to differences in reporting and data coverage, countries are clearly detecting more domestic trafficking nowadays.

These shifts indicate that the common understanding of the trafficking crime has evolved. A decade ago, trafficking was thought to mainly involve women trafficked from afar into an affluent country for sexual exploitation. Today, criminal justice practitioners are more aware of the diversity among offenders, victims, forms of exploitation and flows of trafficking in persons, and the statistics may reflect this increased awareness.

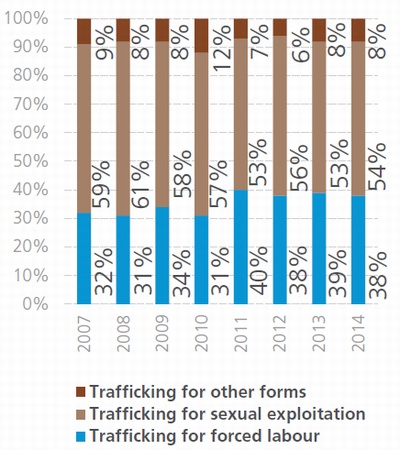

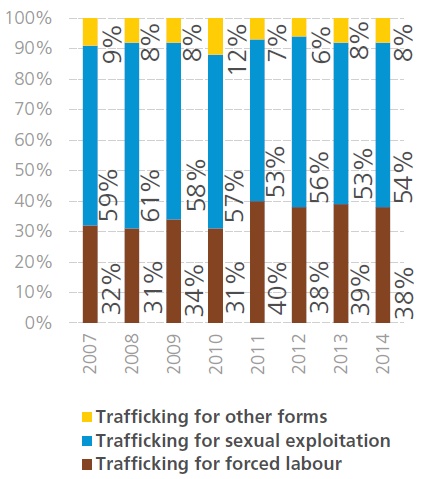

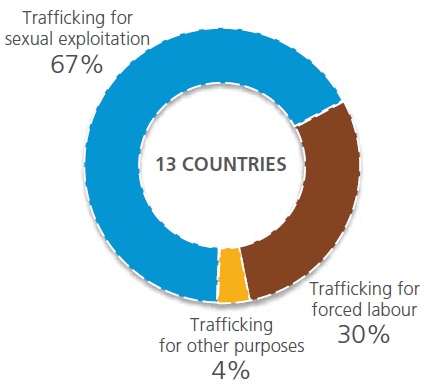

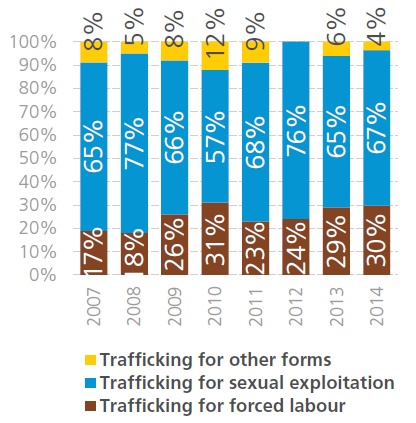

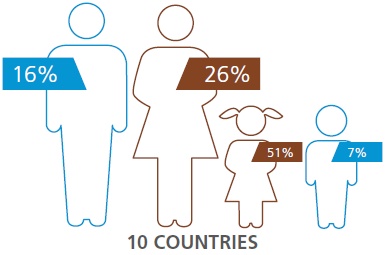

Trends in the forms of exploitation among detected trafficking victims, 2007-2014

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

3) VICTIMS AND TRAFFICKERS OFTEN HAVE THE SAME BACKGROUND

Traffickers and their victims often come from the same place, speak the same language or have the same ethnic background. Such commonalities help traffickers generate trust to carry out the trafficking crime.

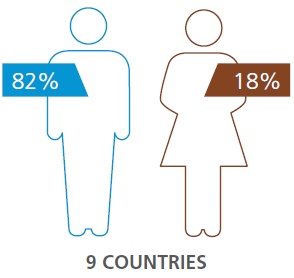

Traffickers rarely travel abroad in order to recruit victims, but they do travel to destination countries to exploit them. As general pattern, traffickers in origin countries are usually citizens of these countries. Traffickers in destination countries are either citizens of these countries or have the same citizenship as the victim(s) they trafficked.

Being of the same gender can also enhance trust. Data from court cases indicate that women are commonly involved in the trafficking of women and girls, in particular. Most of the detected victims of trafficking in persons are females; either women or underage girls.

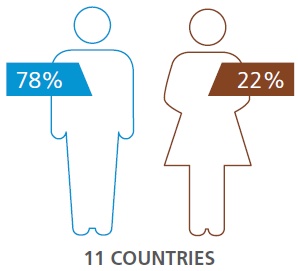

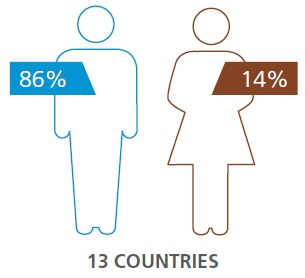

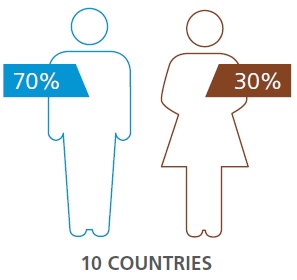

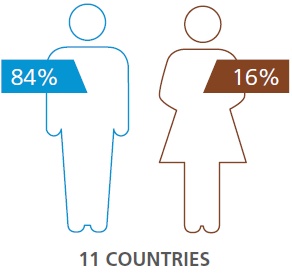

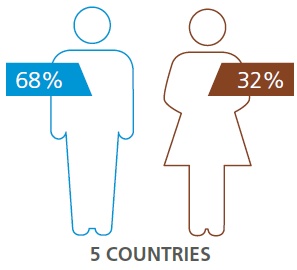

While traffickers are overwhelmingly male, women comprise a relatively large share of convicted offenders, compared to most other crimes. This share is even higher among traffickers convicted in the victims' home country. Court cases and other qualitative data indicate that women are often used to recruit other women.

Family ties can also be abused to carry out trafficking crimes. For instance, this is seen in cases of relatives entrusted with the care of a family member who break their promise and profit from the family member's exploitation.

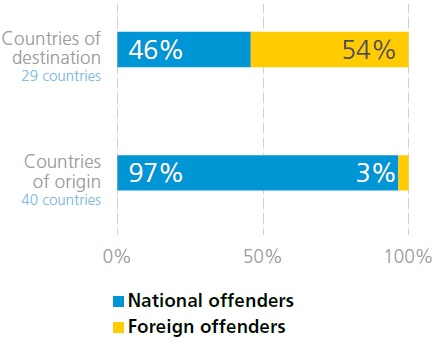

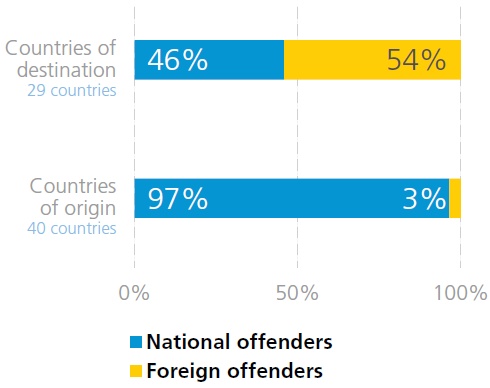

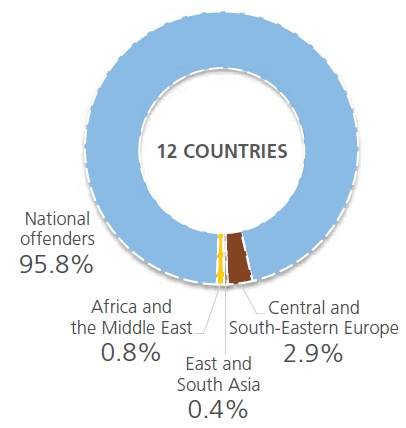

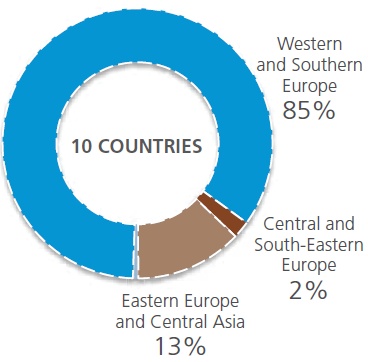

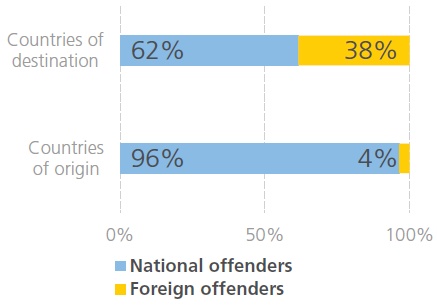

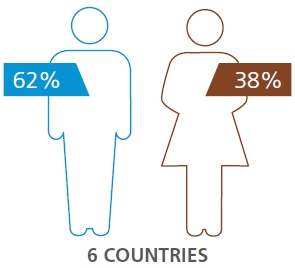

Shares of national and foreign citizens (relative to the convicting country) among convicted traffickers, by countries of origin and destination, 2014 (or most recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data

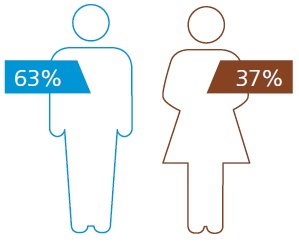

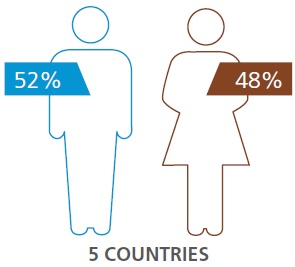

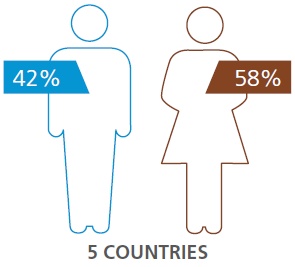

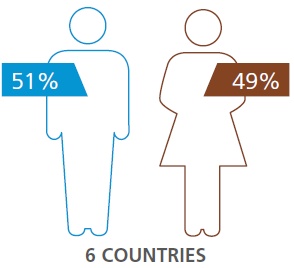

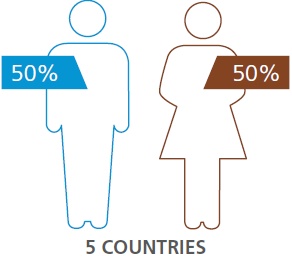

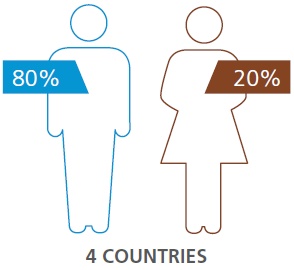

Shares of persons convicted of trafficking in persons, by sex, 2014 (or most recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data

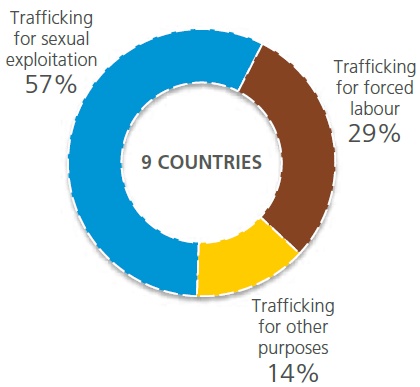

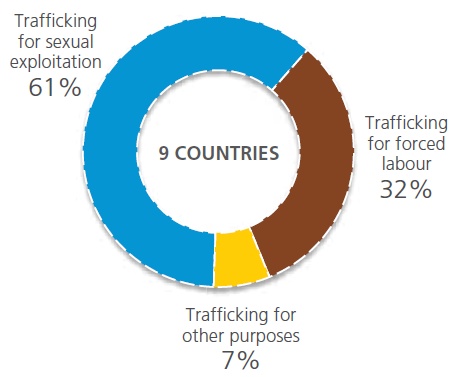

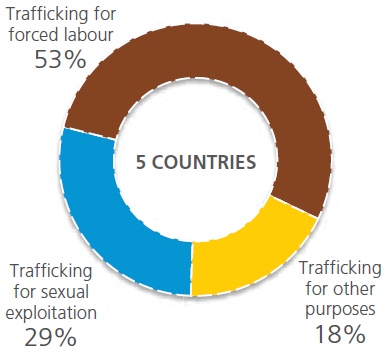

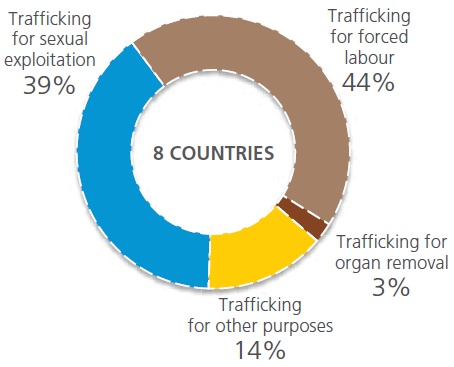

4) PEOPLE ARE TRAFFICKED FOR MANY EXPLOITATIVE PURPOSES

Trafficking for sexual exploitation and for forced labour are the most prominently detected forms, but trafficking victims can also be exploited in many other ways. Victims are trafficked to be used as beggars, for forced or sham marriages, benefit fraud, production of pornography or for organ removal, to mention some of the forms countries have reported.

Trafficking for various types of marriage has been sporadically reported in the past, but is now emerging as a more prevalent form. In South-East Asia, this often involves forced marriages, or unions without the consent of the woman (or girl). Trafficking for sham marriages mainly takes place in affluent countries.

Trafficking for forced labour in the fishing industry is commonplace in several parts of the world. This can happen, for example, on board big fishing vessels on the high seas, carried out by large companies that trade fish internationally, or in on-land processing facilities. It can also happen more locally, such as in African lake areas where the fishing tends to be small-scale and the catch is sold in street markets.

Trafficking for sexual exploitation and for forced labour in a range of economic sectors are

reported nearly everywhere. At least 10 countries have reported trafficking for the removal of

organs. Other forms of reported trafficking, such as the ones mentioned above, are sometimes

locally acute, but less internationally widespread.

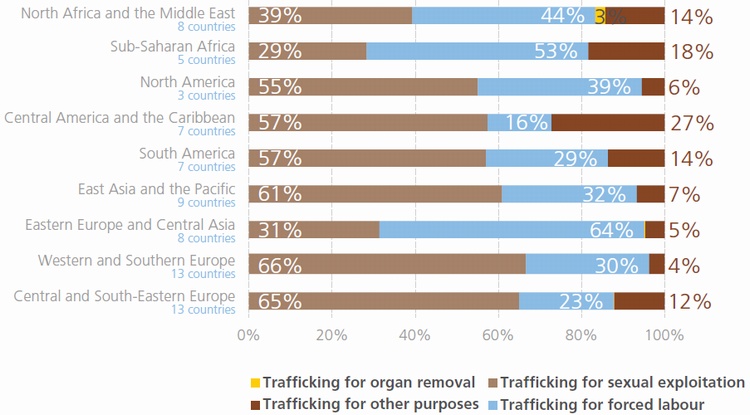

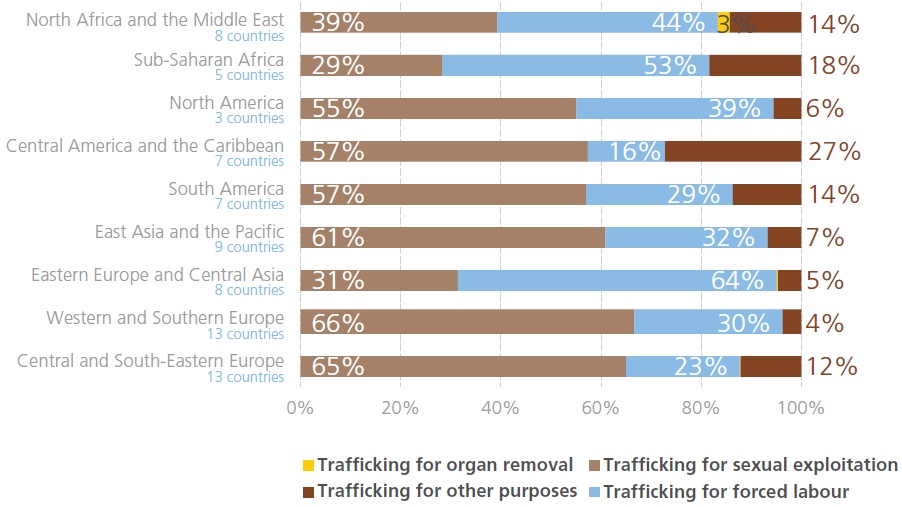

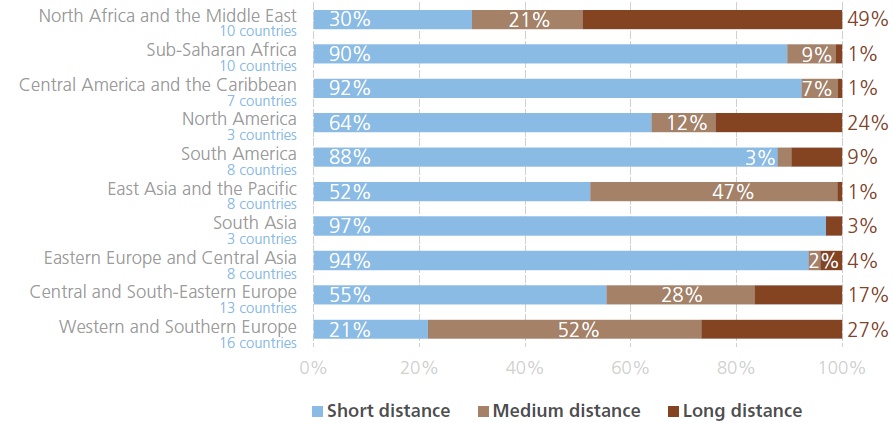

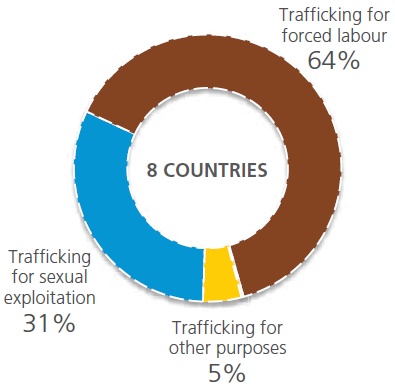

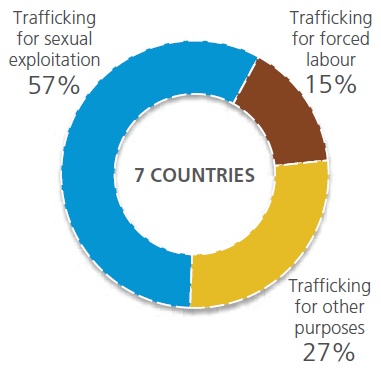

Share of forms of exploitation among detected trafficking victims, by region of detection, 2012-2014 (or most recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

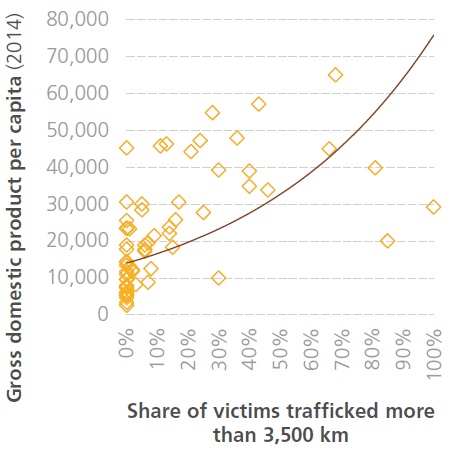

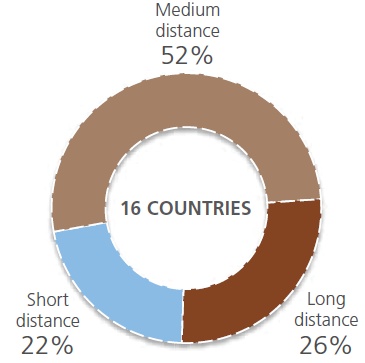

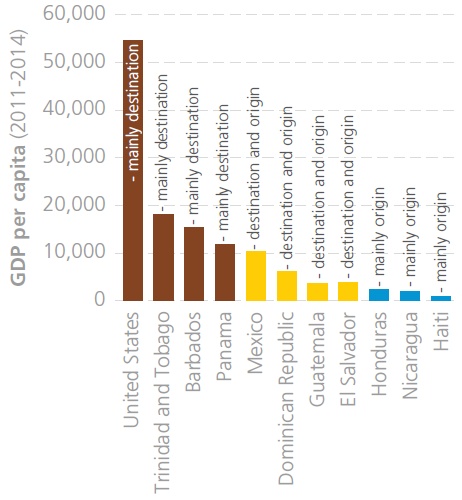

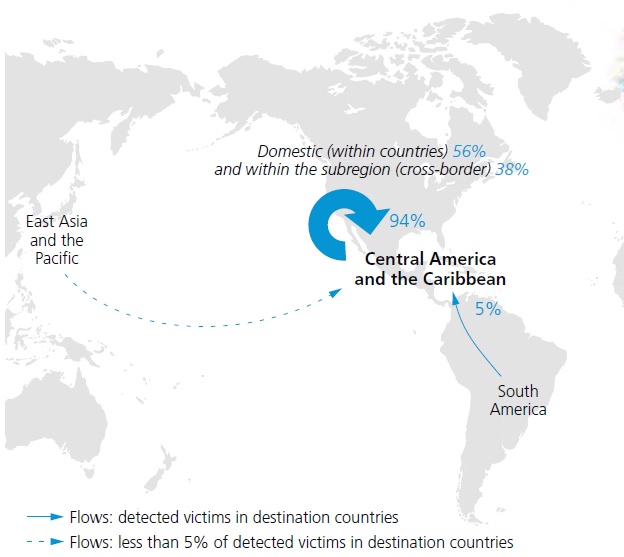

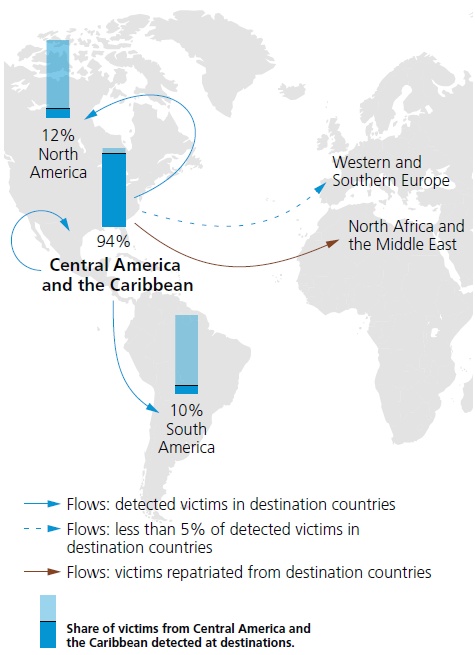

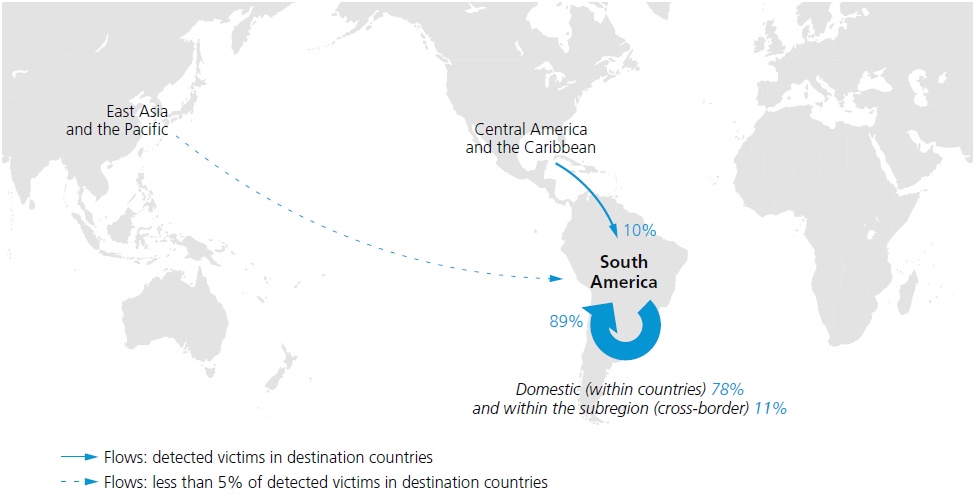

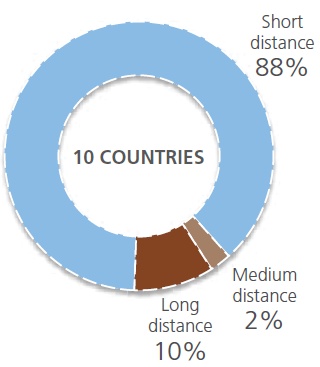

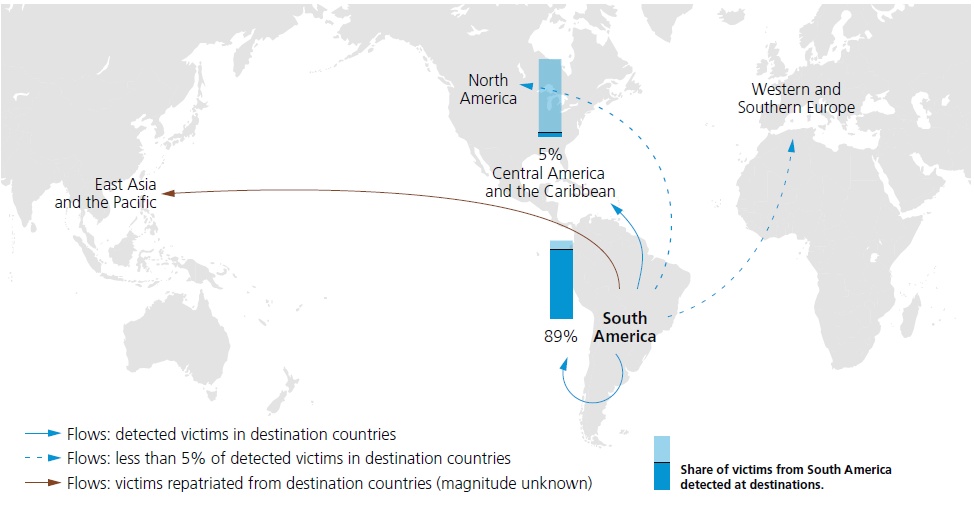

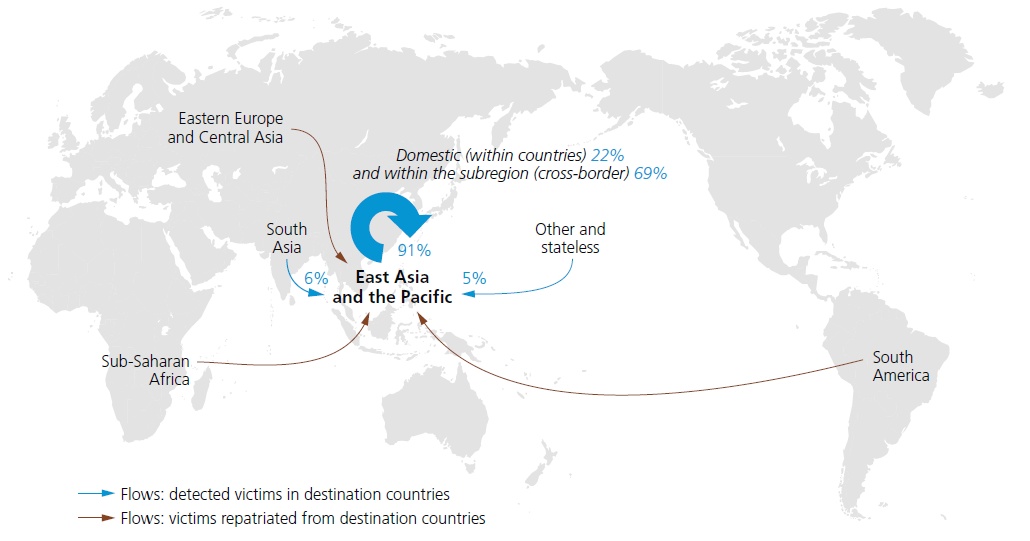

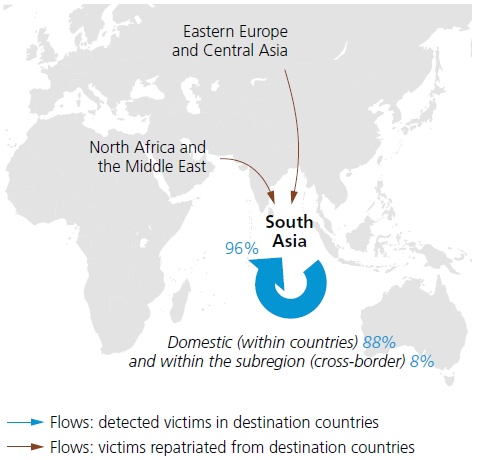

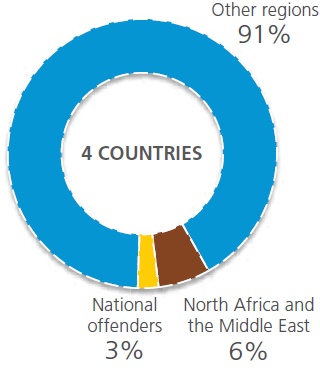

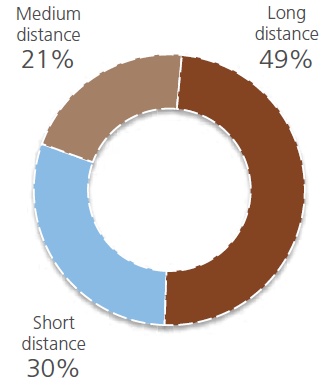

5) CROSS-BORDER TRAFFICKING FLOWS OFTEN RESEMBLE REGULAR MIGRATION FLOWS

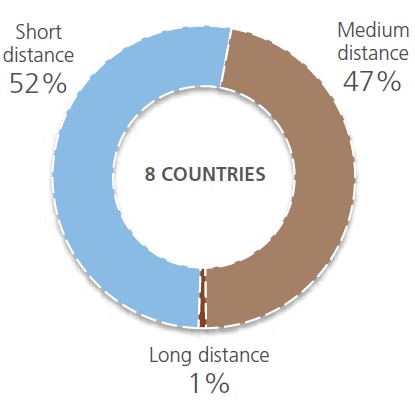

Although many cases of trafficking in persons do not involve the crossing of international borders – some 42 per cent of the detected victims are trafficked domestically - there are some links between cross-border trafficking and regular migration flows. Certain trafficking flows resemble migration flows, and some sizable international migration flows are also reflected in cross-border trafficking flows.

The analysis of country-level data on detected trafficking victims and recently arrived regular migrants reveals that trafficking in persons and regular migration flows broadly resemble each other for some destination countries in different parts of the world.

Many factors can increase a person's vulnerability to human trafficking during the migration process, however. The presence of transnational organized crime elements in the country of origin, for instance, is significant in this regard, and a person's socio-economic profile can also have an impact.

Main destinations of transregional flows and their significant origins, 2012-2014

Source: UNODC.

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

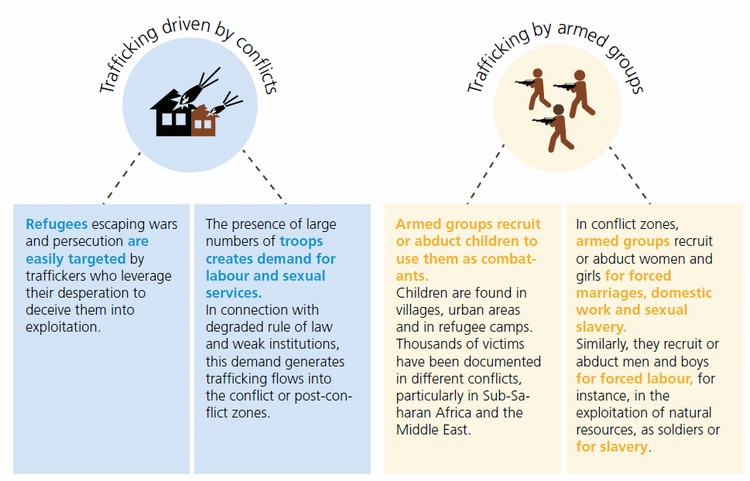

6) CONFLICT CAN HELP DRIVE TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS

People escaping from war and persecution are particularly vulnerable to becoming victims of trafficking. The urgency of their situation might lead them to make dangerous migration decisions. The rapid increase in the number of Syrian victims of trafficking in persons following the start of the conflict there, for instance, seems to be one example of how these vulnerabilities play out.

Conflicts create favourable conditions for trafficking in persons, but not only by generating a mass of vulnerable people escaping violence. Armed groups engage in trafficking in the territories in which they operate, and they have recruited thousands of children for the purpose of using them as combatants in various past and current conflicts. While women and girls tend to be trafficked for marriages and sexual slavery, men and boys are typically exploited in forced labour in the mining sector, as porters, soldiers and slaves.

7) TRAFFICKING THE MOST VULNERABLE: CHILDREN

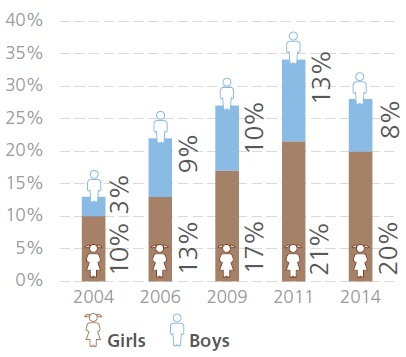

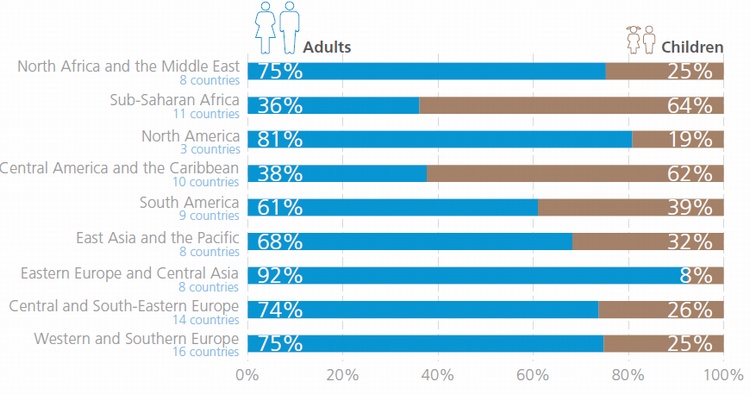

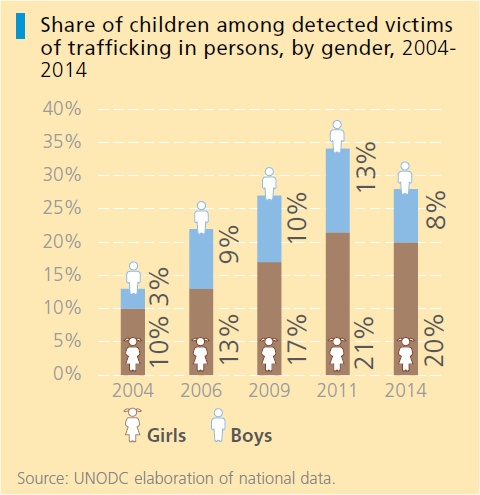

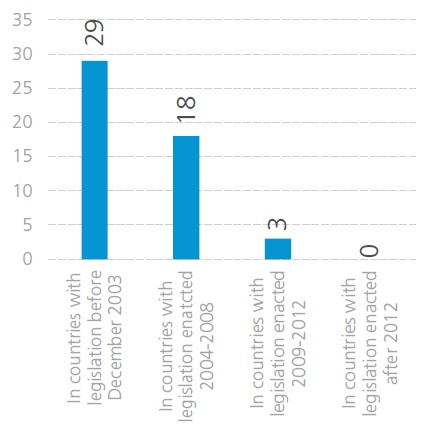

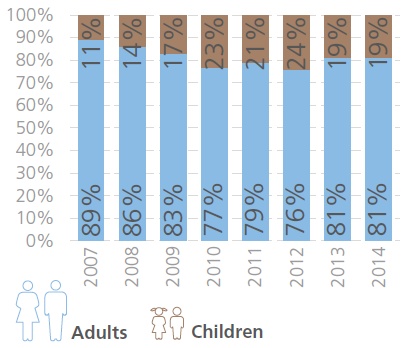

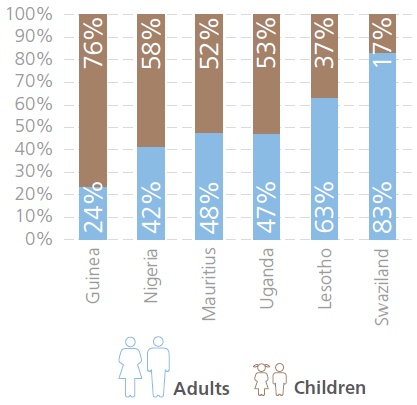

The share of detected child victims has returned to levels last seen in 2009, after seven years of increases. Despite this trend, still more than a quarter of the detected trafficking victims in 2014 were children.

In Sub-Saharan Africa and Central America and the Caribbean, a majority of the detected victims are children. There are several reasons, such as demographics, socioeconomic factors, legislative differences and countries' institutional frameworks and priorities. There seems to be a relation between a country's level of development and the age of detected trafficking victims. In the least developed countries, children often comprise large shares of the detected victims.

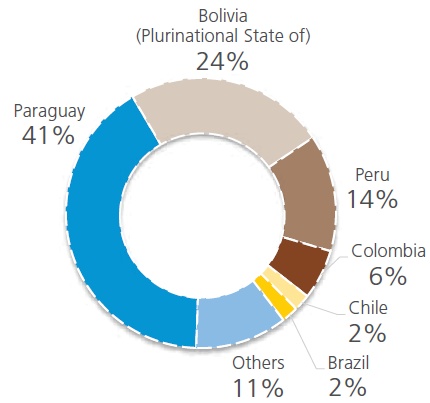

There are clear regional differences with regard to the sex of detected child victims. Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa detect more boys than girls, which seems to be connected with the large shares of trafficking for forced labour, child soldiers (in conflict areas) and begging reported in that region. In Central America and the Caribbean and South America, on the other hand, girls make up a large share of the detected victims, which could be related to the fact that trafficking for sexual exploitation is the most frequently detected form there.

Share of children among detected victims of trafficking in persons, by gender, selected years

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

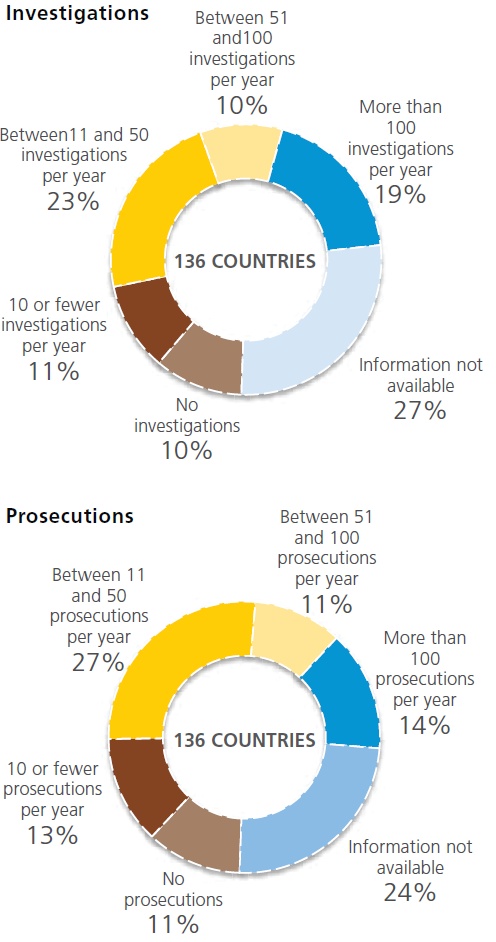

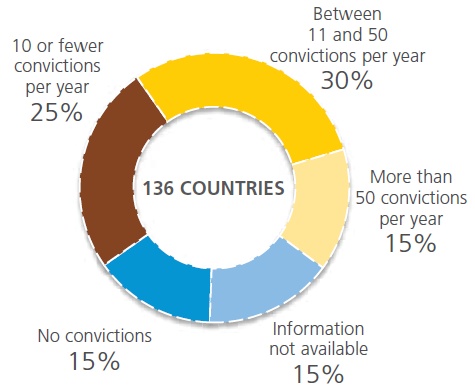

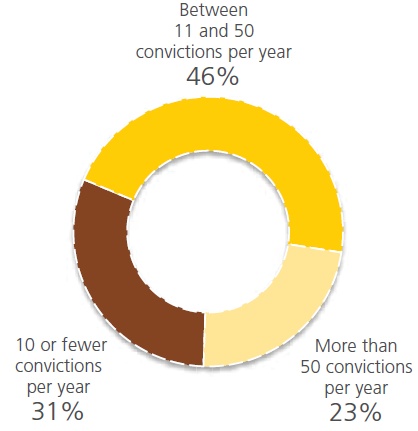

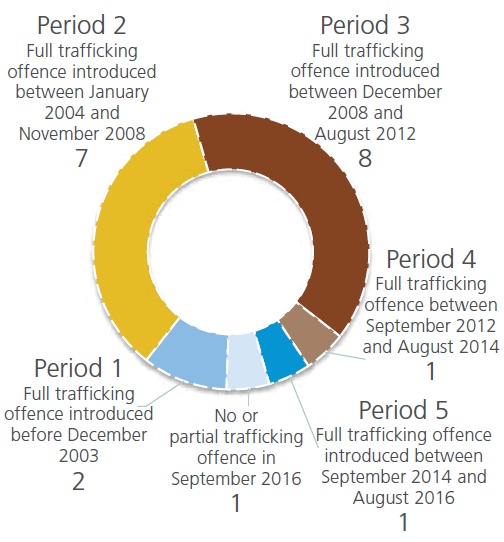

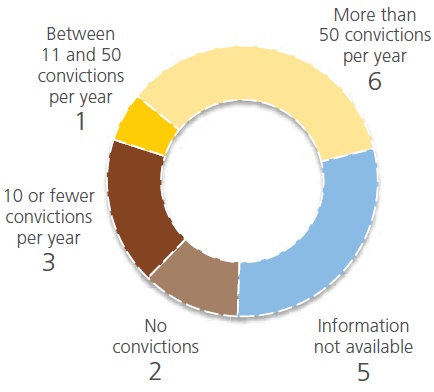

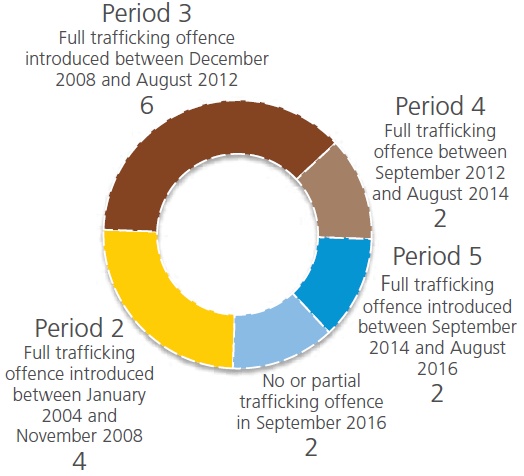

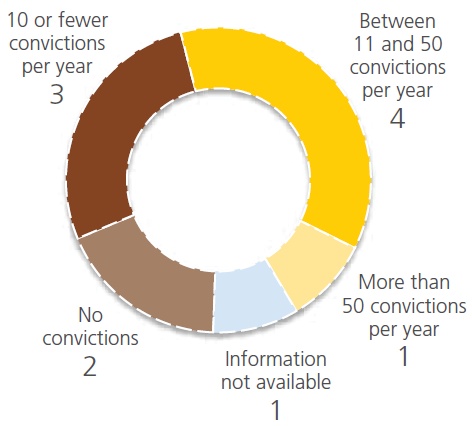

8) SOLID LEGISLATIVE PROGRESS, BUT STILL VERY FEW CONVICTIONS

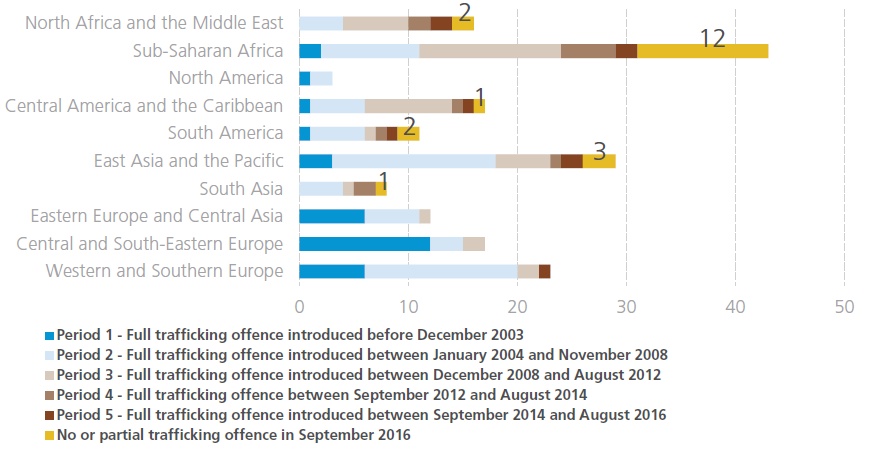

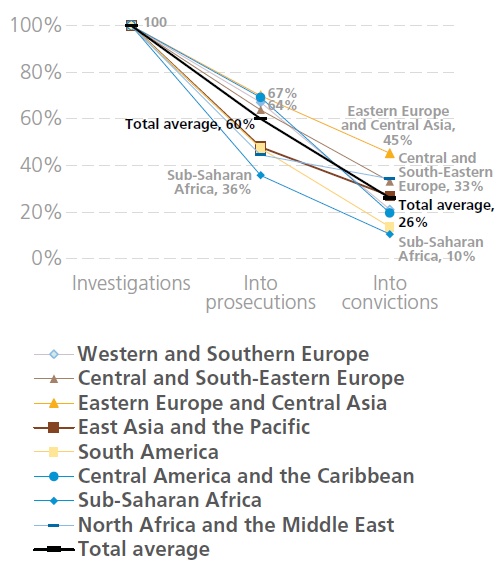

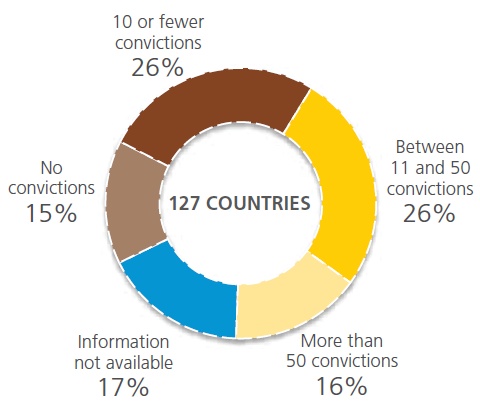

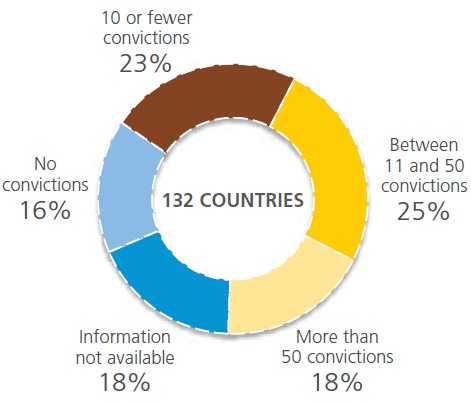

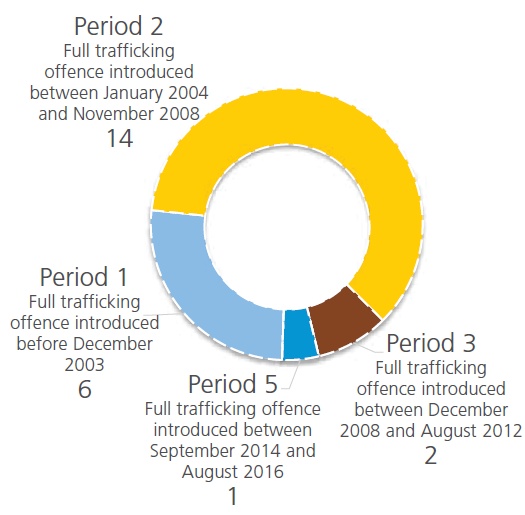

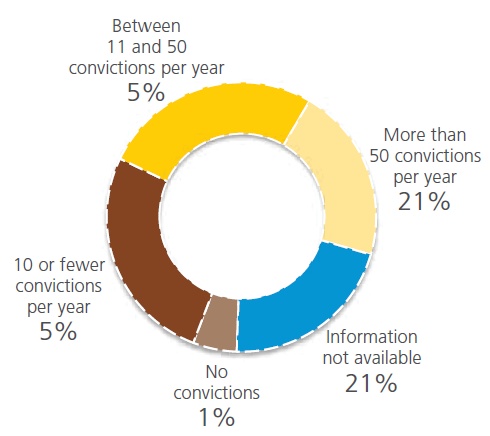

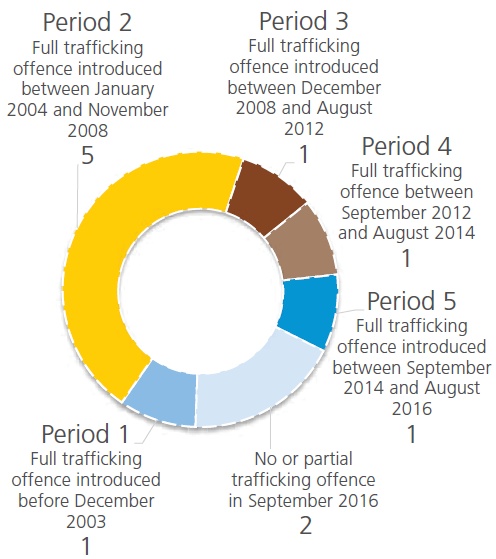

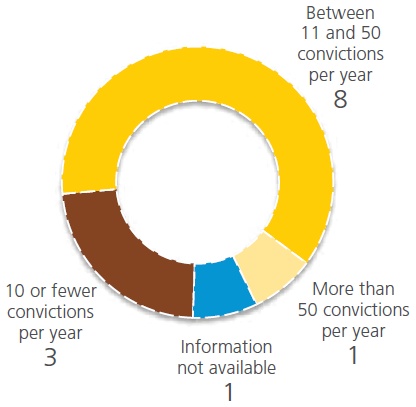

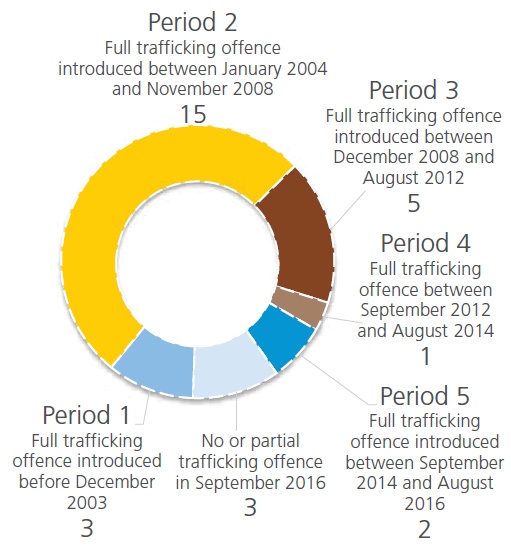

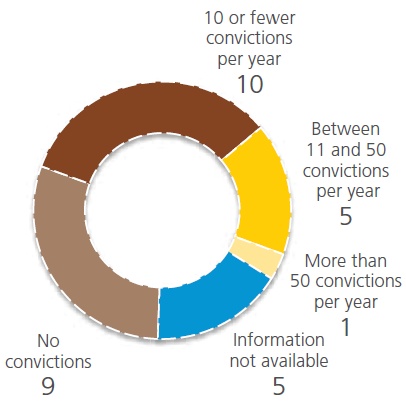

The number of countries with a statute that criminalizes most forms of trafficking in persons in line with the definition used by the UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol increased from 33 in 2003 (18 per cent) to 158 in 2016 (88 per cent). This rapid progress means that more victims are assisted and protected, and more traffickers are put behind bars.

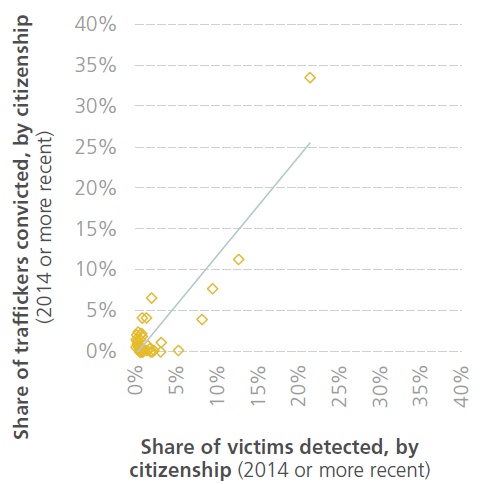

However, most national legislation is recent, having been introduced during the last eight to 10 years. As a consequence, the average number of convictions still remains low. The longer countries have had comprehensive legislation in place, the more convictions are recorded, indicating that it takes time and dedicated resources for a national criminal justice system to acquire sufficient expertise to detect, investigate and successfully prosecute cases of trafficking in persons.

The ratio between the number of traffickers convicted in the first court instance and the number of victims detected is about 5 victims per convicted offender. Although most countries now have the appropriate legal framework for tackling trafficking crimes, the large discrepancy between the number of detected victims and convicted offenders indicates that many trafficking crimes still go unpunished.

Criminalization of trafficking in persons with a specific offence covering all or some forms as defined in the UN Protocol, numbers and shares of countries, 2003-2016

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

INTRODUCTION

Trafficking in persons, migration and conflict

Against a backdrop of sustained global population growth, affordable telecommunication and persistent economic inequalities, human mobility has increased. In 2015, the United Nations estimated that there were some 244 million international migrants across the world; an increase of more than 40 per cent since the year 2000 (173 million). |1| Additionally, the 2009 Human Development Report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) estimated that there are some 740 million internal migrants, moving within their countries. |2| Many people are escaping war and persecution. In 2016, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that, at the end of 2015, more than 65 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, violence or human rights violations; an increase of 6 million compared to just 12 months earlier. |3|

There is a clear link between the broader migration phenomenon and trafficking in persons. It is true that traffficking victims are not always migrants and, according to the legal definition, victims do not need to be physically moved to be considered as having been trafficked. The stories of victims of trafficking, however, often start as brave attempts to improve their life, as is also the case with many migration stories. Those who end up in the hands of traffickers often envisioned a better life in another place; across the border, across the sea, in the big city or in the richer parts of the country. Traffickers, whether they are trafficking organizations, legally registered companies, 'loners' acting on their own or family members of the victim, often take advantage of this aspiration to deceive victims into an exploitative situation.

Trafficking in persons is driven by a range of factors, many of which are not related to migration. At the same time, some people who migrate and refugees escaping from conflict and persecution are particularly vulnerable to being trafficked. The desperation of refugees can be leveraged by traffickers to deceive and coerce them into exploitation. War and conflict can exacerbate trafficking in persons: not only may those who escape violence turn to traffickers in their hope of finding a safe haven, but armed groups also exploit victims for various purposes in conflict areas.

The thematic focus of the 2016 edition of the Global Report investigates how migrants and refugees can be vulnerable to trafficking in persons en route or at destination. This focus complements the findings of previous editions, which have looked at socio-economic factors and the role of transnational organized criminal groups in trafficking in persons. This edition also looks at the particular condition of people escaping war, conflict and persecution.

Organization of the report

This edition of the Global Report on Trafficking in Persons consists of three main analytical chapters. Chapter I provides a global overview of the patterns and flows of trafficking in persons and an overview of the status of country-level legislation and the criminal justice response to the trafficking crime. Chapter II presents an analysis of trafficking in persons in the broader perspective of migration and conflict, and chapter III contains in-depth analyses by region.

The detailed country profiles, available at the Global Report website (www.unodc.org/glotip), present the country-level information that was collected for the preparation of this edition. They are divided into three main sections: the country's legislation on trafficking in persons, suspects and investigations, and victims of trafficking.

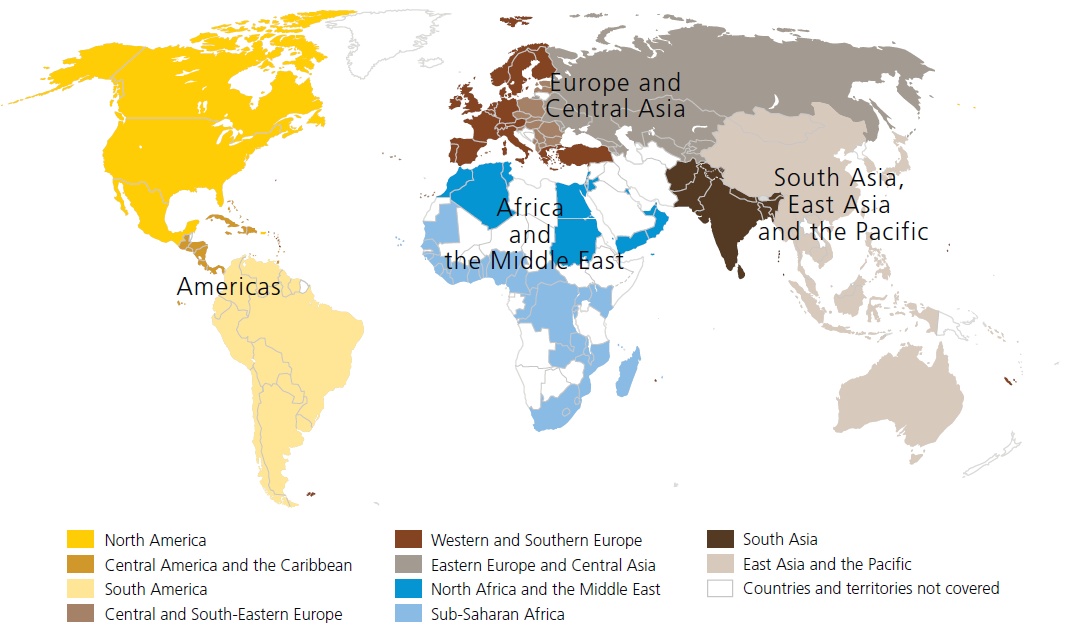

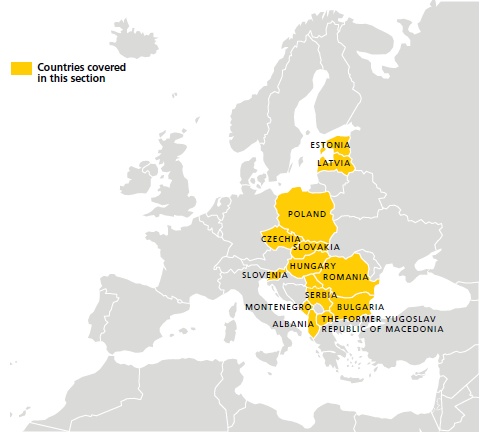

The 136 countries covered by the data collection were categorized into eight regions: Western and Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, North and Central America and the Caribbean, South America, East Asia and the Pacific, South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and North Africa and the Middle East. The order of presentation of the regional overviews is based on the size of the sample used for the analysis in each region. As European countries reported the highest number of victims during the period considered, the two European regions are presented first. They are followed by the two regions of the Americas, then Asia and finally Africa and the Middle East.

Since many countries in Western and Central Europe provided thorough and comprehensive data, it was possible to undertake more detailed analyses for this region. Therefore, the region was divided into two subregions, namely Western and Southern Europe, and Central and South-Eastern Europe. The specific country breakdown for these subregions is presented within the regional overview. Similarly, the region of North and Central America and the Caribbean consists of North America, and Central America and the Caribbean. Occasionally, for analytical purposes, other country aggregations were considered. In those cases, the countries included have been listed either in the text or in a footnote.

Percentages in figures throughout the report may not always add up to 100% due to rounding.

Regional and subregional designations used in this report

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

Explanation of key terms

This section aims to explain some key terms that are frequently used in the context of trafficking in persons. At times, these definitions have been simplified in order to ease understanding, however, full legal definitions of terms have been supplied in the accompanying references.

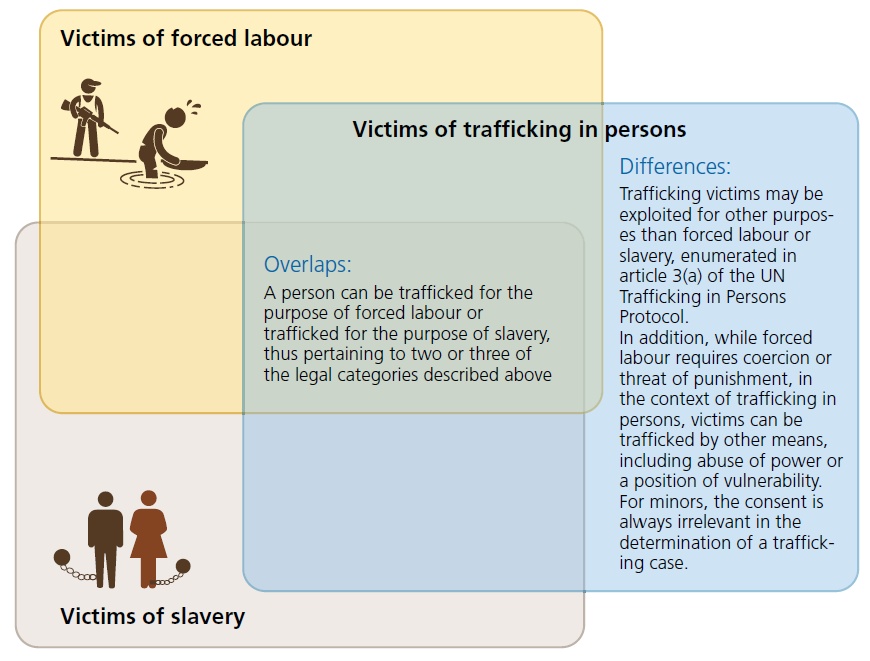

Trafficking in persons in the context of exploitation

Trafficking in persons |4| is a crime that includes three elements: 1) the ACT of recruiting, transporting, transferring, harbouring or receiving a person; 2) by MEANS of e.g. coercion, deception or abuse of vulnerability; 3) for the PURPOSE OF EXPLOITATION. Forms of exploitation specified in the definition of trafficking in persons include, sexual exploitation, slavery and forced labour, among others. Slavery and forced labour are also addressed in distinct international treaties.

Overlaps and differences between victims of trafficking, forced labour and slavery

Note: The areas drawn in this figure are not intended to represent actual size population affected or covered by these different legal concepts.

A victim of forced labour |5| is any person in any form of work or service which is exacted from him/her under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily. |6|

A victim of slavery |7| is a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised.

Despite the different legal definitions that exist in the relevant international instruments, people affected by these three violations are not always distinct.

Overlaps between victims of trafficking in persons and populations affected by forced labour and/or slavery: A person can be trafficked for the purposes of slavery or forced labour, thus pertaining to two or three of the legal categories described above.

Differences between victims of trafficking in persons and populations affected by forced labour and/or slavery: trafficking victims may be exploited for other purposes than forced labour or slavery, enumerated in article 3(a) of the UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol. |8| In addition, while forced labour requires coercion or threat of punishment, in the context of trafficking in persons, victims can be trafficked by other means, including abuse of power or a position of vulnerability. For minors, the consent is always irrelevant in the determination of a trafficking case.

The term modern slavery has recently been used in the context of different practices or crimes such as trafficking in persons, forced labour, slavery, but also child labour, forced marriages and others. The common denominator of these crimes is that they are all forms of exploitation in which one person is under the control of another. The term has an important advocacy impact and has been adopted in some national legislation to cover provisions related to trafficking in persons, however the lack of an agreed definition or legal standard at the international level results in inconsistent usage.

While the legal definitions and, in certain cases the victim populations, of these different crimes may overlap to some extent, the use of one related national law over another makes great differences, especially to victims of trafficking. National legislations that comply with the UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol include a number of protection and assistance measures that are not available under other legal frameworks. |9| In particular, States parties have the duty to protect the privacy and identity of victims of trafficking, to provide information on relevant court or other proceedings and assistance to enable their views to be heard in the context of such proceedings. In addition, States parties are obligated to ensure that victims of trafficking in persons can access remedies, including compensation. States parties must also consider providing for the physical safety of victims and to providing housing, counselling, medical, psychological and material assistance as well as employment, educational and training opportunities to victims of trafficking.

Adherence to the Protocol also triggers certain provisions under the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (which the Protocol supplements). States parties have a broad array of mutual tools at their disposal for prosecuting trafficking in persons cases that are unavailable if there is no compliance with the convention, such as tools that address the illicit income derived from such crimes, like money-laundering, confiscation and seizure; international cooperation measures such as mutual legal assistance and extradition; and law enforcement cooperation measures such as joint investigations. Not fully utilizing these tools to prosecute trafficking in persons results in a piecemeal approach that organized criminals exploit to their advantage every day.

Trafficking in persons in the context of migration

The crime of trafficking in persons does not need to involve a border crossing. However, many detected victims are international migrants, in the sense that their citizenship differs from the country in which they were detected as trafficking victims.

Migrant smuggling is a crime concerning the facilitation of the illegal border crossing of a person into a State party of which a person is not a national or a resident in order to obtain a financial or other material benefit. |10|

Refugee is someone who has been forced to flee his/her country to preserve life or freedom. Refugees are entitled to protection under international law. |11|

International migrant is used in this report to refer to any person who changes his or her country of usual residence. |12|

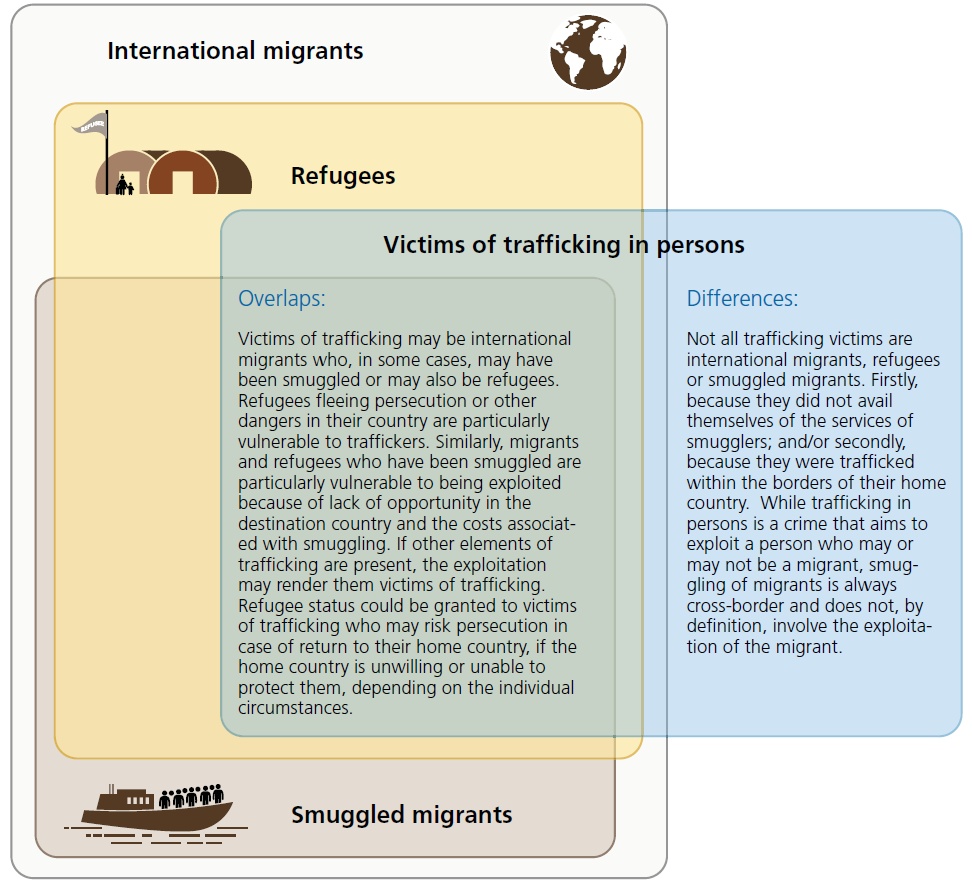

Overlaps and differences between victims of trafficking, international migrants, refugees and smuggled migrants

Note: The areas drawn in this figure are not intended to represent actual size population affected or covered by these different legal concepts.

Overlaps between victims of trafficking in persons, refugees and smuggled migrants:

Victims of trafficking may be migrants who have been smuggled and may also be refugees, amongst others. Refugees fleeing persecution or other dangers in their country are particularly vulnerable to traffickers. Similarly, migrants and refugees who have been smuggled are particularly vulnerable to being exploited because of lack of opportunity in the destination country and the costs associated with smuggling. If other elements of trafficking are present, the exploitation may render them victims of trafficking. Refugee status could be granted to victims of trafficking who may risk persecution in case of return to their home country, if the home country is unwilling or unable to protect them, depending on the individual circumstances.

Differences between victims of trafficking in persons, refugees and smuggled migrants:

Not all trafficking victims are smuggled migrants or refugees. Firstly, because they did not avail themselves of the services of smugglers; and/or secondly, because they were trafficked within the borders of their home country. While trafficking in persons is a crime that aims to exploit a person who may or may not be a migrant, smuggling of migrants is always cross-border and does not, by definition, involve the exploitation of the migrant.

Similar to the term modern slavery in the exploitative context, the term mixed migration is used to cover different terms in the migration context. Mixed migration generally refers to complex population movements, made up of people that have different reasons for moving and distinct needs including refugees, smuggled migrants and victims of trafficking, and often use the same routes and means of transportation on their travels.

In large-scale movements, refugees and migrants often face perilous journeys in which they risk a range of human rights violations and abuse from traffickers, smugglers and other actors. Furthermore, they may fall in and out of various legal categories in the course of their journey and different protection frameworks may become applicable to them due to changes in fundamental circumstances (that is, they become a refugee sur place; they become stateless due to arbitrary deprivation of their citizenship; or they become victims of trafficking).

Policy considerations

- Most detected cases of trafficking in persons involve more than one country, and most (57 per cent) of the detected victims (2012-2014) moved across at least one international border (p.41). The UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and the supplementing UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol, which enjoy nearly universal ratification, provide States Parties with a series of tools to enhance international cooperation to tackle trafficking. Making better and more frequent use of these tools, including mutual legal assistance, joint investigations and special investigative techniques, could invigorate efforts to detect and prosecute complex cross-border cases of trafficking in persons.

- The regional and time-period analysis of the legislative and criminal justice response (p.49) shows that different parts of the world are at different stages in the implementation of effective counter-trafficking policy. Technical assistance to support Member States to prevent and combat trafficking in different parts of the world needs to be tailored accordingly. In some parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, there is a need to develop legal frameworks; in parts of the world where anti-traffick-ing legislation has been recently introduced (Southern Africa, North Africa, parts of the Middle East, parts of South America) capacity-building assistance to accelerate the use of national frameworks in accordance with international standards is more needed. In countries with long-standing legislation on trafficking in persons, for example, in European subregions, interventions should focus on identifying and protecting more victims, and convicting more traffickers.

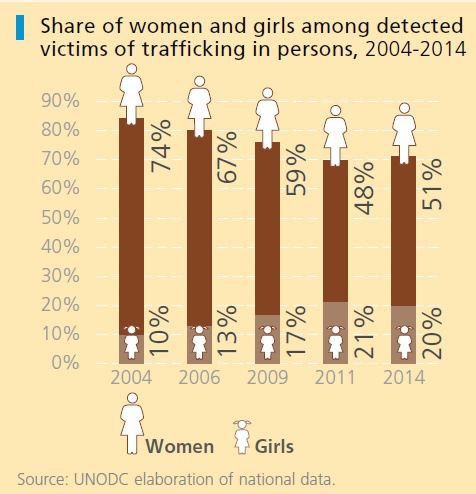

- Trafficking in persons mainly affects women and girls (p. 23), while the share of women among convicted trafficking offenders is much larger than for other crimes (p.33). Laws and policies that prevent and combat trafficking should be designed to take into consideration the particular vulnerability women face with regard to trafficking crimes. Countries may also consider strengthening provisions for assistance to and protection of victims.

- After women, children remain the second largest category of detected victims of trafficking in persons across the world (p. 23). Domestic frameworks on child protection and trafficking in persons, where relevant, should address the specific risk factors that expose children, particularly unaccompanied migrant children, to trafficking situations. Moreover, undertaking enhanced prevention efforts may help highlight how children may become vulnerable to being trafficked and take practical action to address those identified vulnerabilities.

- The Global Report shows that the citizenships of detected victims of trafficking in persons broadly correspond to the citizenships of regular migrants that arrived during the same period (p. 57). Although the links between migration and trafficking in persons are not clear-cut, it appears that the vulnerability to being trafficked is greater among refugees and migrants in large movements, as recognized by Member States in the New York declaration for refugees and migrants of September 2016. Therefore, migration and refugee policies should take into consideration the vulnerability of migrants and refugees to trafficking in persons and attempt to ensure that programmes for the identification of and support to victims of trafficking are a core component of refugee protection systems.

- There is a positive correlation between the duration of existence of national trafficking in persons legislation and the number of trafficking convictions registered in a country (p.52). Most countries have now adopted legislation that criminalizes trafficking in persons according to the UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol (p. 48), yet global conviction rates remain low. This might be related to the relatively recent nature of national legal frameworks in many countries. Accelerating the implementation of the domestic legislation by carrying out awareness-raising, training and other capacity-building activities on the use of legislation may now be useful in rapidly enhancing the capacity of national criminal justice systems to identify, investigate and prosecute cases of trafficking in persons.

- This and previous editions of the Global Report have identified several enabling factors that can increase people's vulnerability to trafficking in persons, such as the presence of transnational organized crime in origin countries, levels of development, irregular migration paths and weak protection structures. This work has only scratched the surface of these complex linkages, however, and more research is needed to better understand the factors that help drive trafficking in persons. Such research would also be applicable in context of the Sustainable Development Goals, and particularly to help monitor progress towards the targets explicitly referencing trafficking in persons (16.2, 5.2 and 8.7).

CHAPTER I

GLOBAL OVERVIEW

PATTERNS OF TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS

UNODC has been collecting data on the patterns and trends of trafficking in persons from official, national criminal justice sources since 2003, and this edition of the Global Report on Trafficking in Persons draws on statistics covering more than a decade. The focus, however, is on the 2012-2014 period.

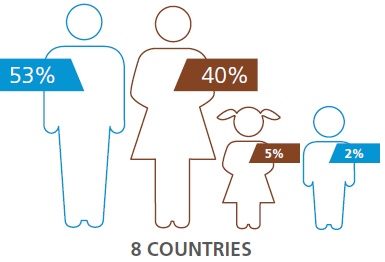

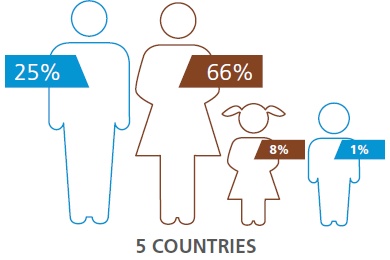

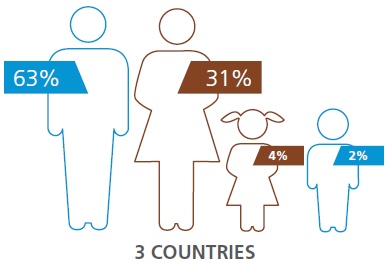

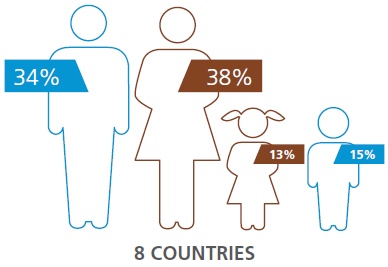

Profile of the victims

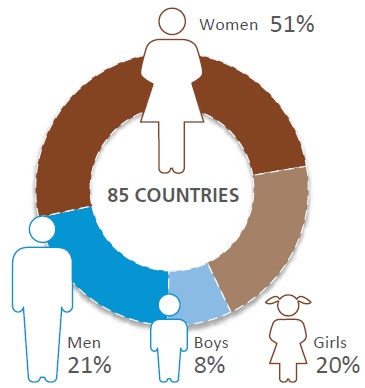

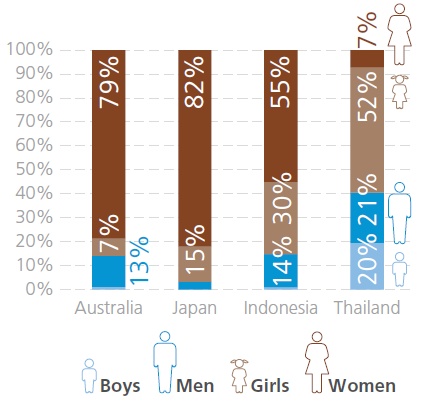

A total of 63,251 victims were detected in 106 countries and territories between 2012 and 2014. Based on the 17,752 victims detected in 85 countries in 2014 for which sex and age were reported, a clear majority were females - adult women and girls – comprising some 70 per cent of the total number of detected victims. Females have made up the majority of detected victims since UNODC started collecting data on trafficking in persons in 2003.

FIG. 1 Detected victims of trafficking in persons, by age* and sex, 2014 (or most recent)

* 'Men' are males aged 18 or older; 'boys' are males 17 and below. 'Women' are females aged 18 or older; 'girls' are females 17 and below.

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

The share of men among detected trafficking victims is increasing

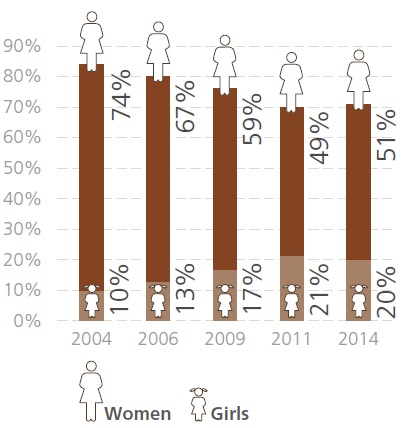

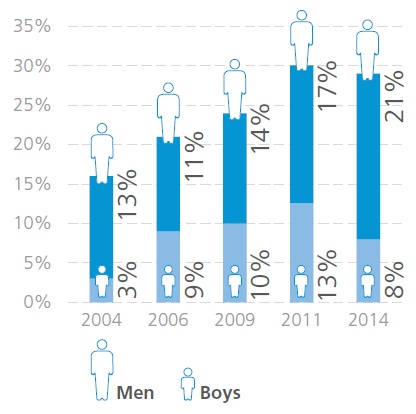

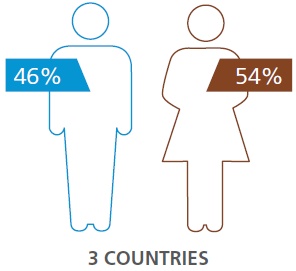

Although women still comprise a majority of detected victims, there has been an overall decrease in the share of female victims over the past decade, from 84 per cent in 2004 to 71 per cent in 2014. The trend for detections of men, in contrast, has been increasing over the same period, and more than 1 in 5 detected trafficking victims between 2012 and 2014 were men.

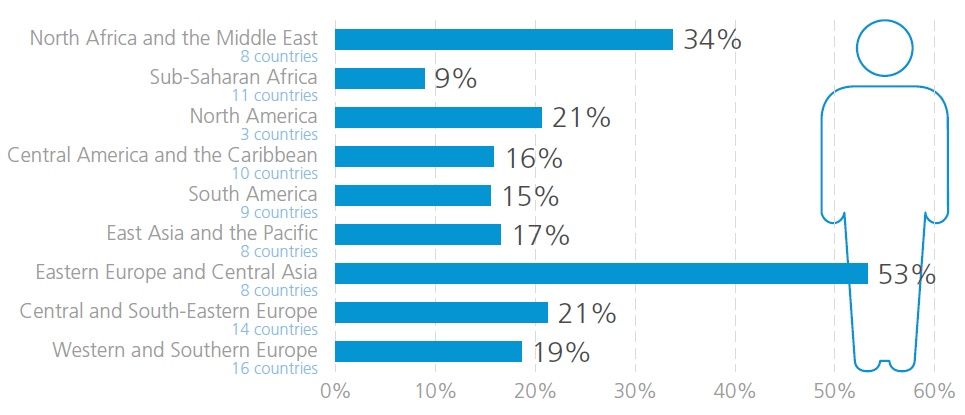

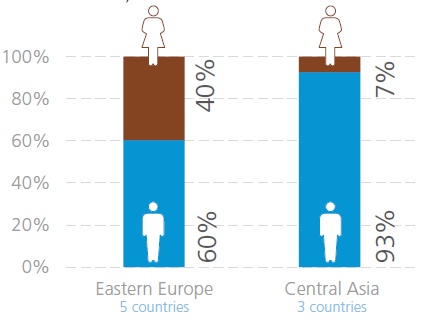

Global averages mask marked regional differences in the profile of victims. In a few regions men represent the majority of detected victims, for example in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, where the share of men exceeded 50 per cent due to widespread detections of men in Central Asia. Similarly, countries in the Middle East detected a proportion of men which was larger than the global average; about one third of the total. The high prevalence of trafficking in men in these two areas may be linked to the frequent detections of trafficking for forced labour.

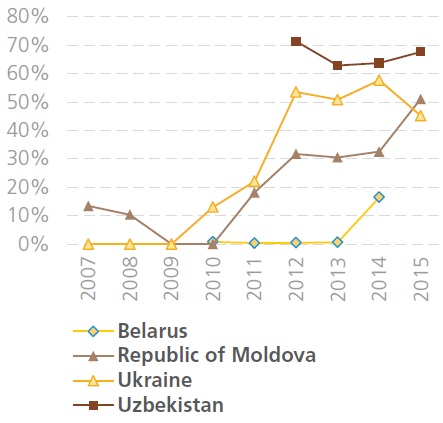

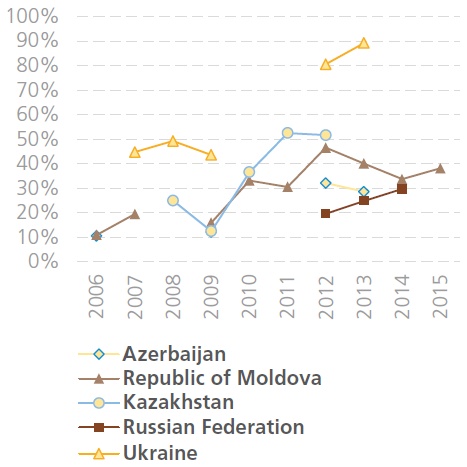

FIG. 3 Trends in the shares of males (men and boys) among detected trafficking victims, selected years

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

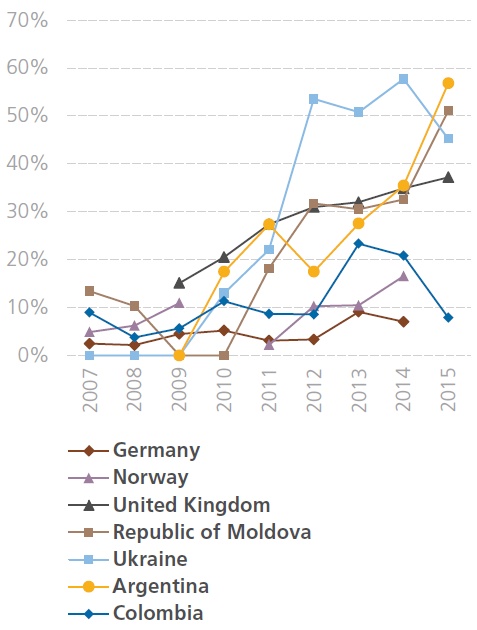

In 25 countries – mostly in Europe, Central Asia and South America – the share of detected men has increased over the last eight years. However, the majority of the countries covered show stable or unclear trends for this indicator.

In other areas, such as Western and Southern Europe, Central and South-Eastern Europe, the Americas and East Asia, the shares of men among victims of trafficking seem to be relatively stable, at around 15-20 per cent. In Sub-Saharan Africa - where children are detected at very high levels - men represent a relatively small share of the detected victims.

Detected male victims – men and boys - are mainly trafficked for forced labour. To a limited extent, male victims are also detected in cases of trafficking for sexual exploitation or for other forms of exploitation, such as begging and the commission of crime.

FIG. 5 Trends in the shares of men among detected trafficking victims, selected countries, 2007-2015

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

FIG. 6 Forms of exploitation among detected male trafficking victims, 2014 (or most recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

Mixed trends for trafficking in children, although in some regions, most detected victims are children

Children remain the second most commonly detected group of victims of trafficking globally after women, ranging from 25 to 30 per cent of the total over the 2012-2014 period. This represents a 5 percentage points decrease from 2011; largely due to reductions in the number of boys detected in 17 reporting countries.

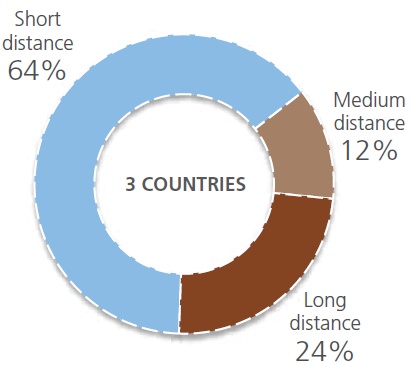

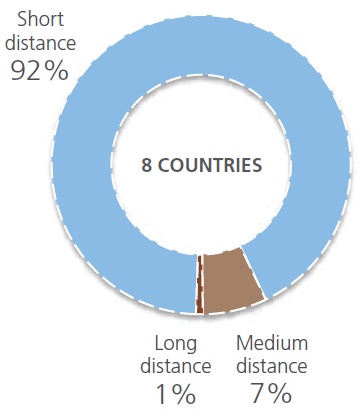

The age profiles of the detected victims vary significantly by region. For instance, countries in Sub-Saharan Africa detect, by far, more child victims (64 per cent) than adult victims; a consistent trend since 2003 when data collection started. Countries in Central America and the Caribbean also mainly detect child victims. The wealthier countries of North America, Europe and the Middle East, on the other hand, typically report relatively small shares of child victims (20-25 per cent).

With current knowledge, it is not possible to provide a thorough explanation of the widely divergent regional figures regarding the detection of child victims. A detailed analysis should consider different factors and assess their impact on the detected level of child trafficking around the world. A first set of considerations relate to the demand for child trafficking, which is the demand for minors in exploitative practices such as sexual, labour and 'other' purposes. This demand includes the potential for profits. |13| For instance, do traffickers more readily exploit children in specific labour sectors, as they may be less likely to demand better working conditions? The demand that drives child trafficking would also include 'cultural practices' which are not conducted by organized traffickers, but by communities. |14| This includes cases of parents selling their children, households using children as domestic servants, or families or teachers forcing children to beg. |15|

Another set of considerations refer to the 'availability' of child victims. As a general statistical result, countries with younger populations tend to have higher levels of child trafficking. |16| This may suggest that in countries where the child population is large, traffickers may target children more easily. Access to education may also be a factor.

Additionally, there are some 'enabling factors' that could help match demand with availability of child trafficking. The presence of such factors could be indicated by the absence of solid institutions dedicated to child protection, including the criminal justice system. Traffickers would encounter fewer obstacles in territories where institutions do not sufficiently protect children, convict traffickers, provide proper education or support communities in keeping children safe. |17| The detection of child victims is more significant in countries with lower levels of human development, while more developed countries report less child trafficking. |18|

FIG. 8 Shares of adults and children among detected trafficking victims, by region, 2014 (or most recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

Some national anti-trafficking institutions may also have a particular focus on child trafficking. This may be the case of some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa that until very recently only had legislation on child trafficking. For this reason, anti-trafficking efforts may still target the trafficking of children more than that of adults.

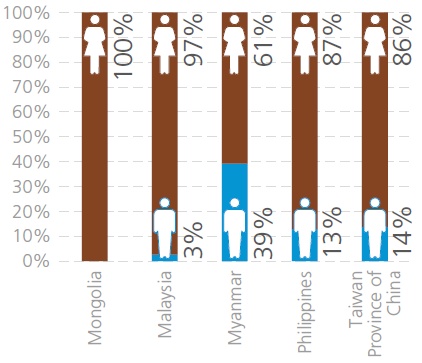

Women and girls trafficked for a variety of purposes

In most areas of the world, the information on detected victims shows that trafficking in persons mainly affects women and girls. Females are chiefly trafficked for sexual exploitation, but also for sham or forced marriages, for begging, for domestic servitude, for forced labour in agriculture or catering, in garment factories, and in the cleaning industry and for organ removal.

The Global Report employs four broad categories of trafficking in persons. This classification is based on the United Nations Trafficking in Persons Protocol, where the following list of purposes is included: "Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs." (Article 3, paragraph (a)). |19|

The first category is trafficking for sexual exploitation, which includes the exploitation of the prostitution of others and similar situations. The second category includes trafficking for forced labour or services, slavery and similar practices and servitude. The third category includes trafficking for the removal of organs, and the fourth and final category is trafficking for "other forms of exploitation". The broad 'other' category includes all forms of trafficking in persons that are not specifically mentioned in the UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol but identified by national legislation or jurisprudence and reported to UNODC through the Global Report questionnaire.

FIG. 9 Share of detected victims of trafficking in persons, by sex and form of exploitation, 2014 (or most recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

About 23,000 victims trafficked for sexual exploitation were detected and reported between 2012 and 2014. The vast majority of them were females; women or girls. The few males trafficked for sexual exploitation are concentrated in Western and Southern Europe and the Americas. During the same period, females also accounted for a considerable number of the detected victims trafficked for forced labour; making up about 37 per cent of the total number of victims for that form.

In some parts of the world, such as East Asia, females account for the majority of detected victims trafficked for forced labour. Much of this trafficking takes the form of domestic servitude, in which victims are exploited in family households. The offenders may be family members, couples acting together or individuals attracting victims from abroad with the promise of a better life.

The description of court cases can provide some examples of how this mode of trafficking is carried out. In Argentina, for example, a girl was brought to that country from the rural parts of the Plurinational State of Bolivia by her aunt. The aunt promised the victim's parents that she would give the girl a proper education in Argentina. However, the girl was exploited as a servant in the household. |20| In the Dominican Republic, a Chinese-Dominican couple recruited a girl in China for exploitation in their household. |21| A similar situation was prosecuted in Austria, where an Austrian citizen forced two Serbian victims into domestic servitude. |22| These examples reveal that victims of trafficking for domestic servitude are often exploited and segregated, with limited chances of being detected and assisted.

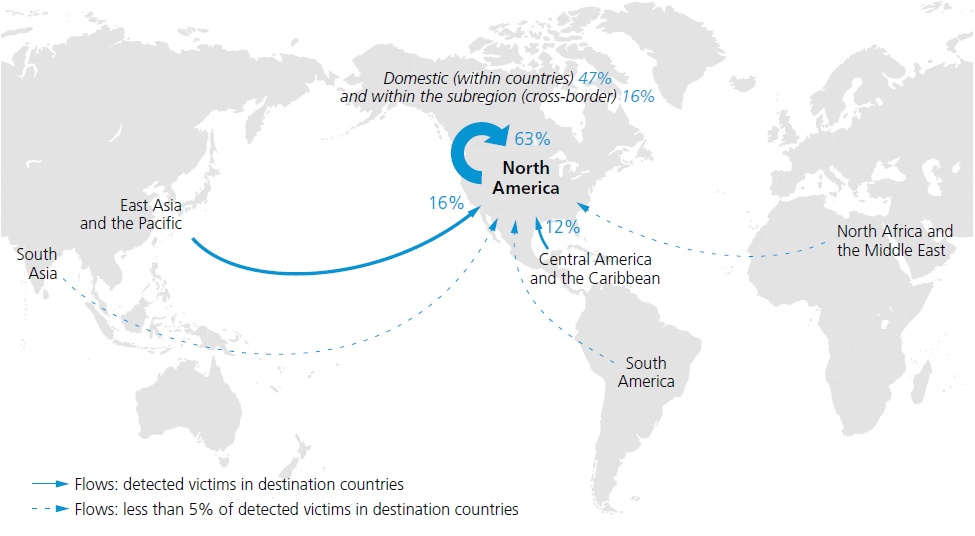

A large number of female victims of trafficking for domestic servitude were also reported in Africa and the Middle East. In that region and in North America, females and males were equally trafficked for forced labour. In North America, domestic servitude is a common form of exploitation, but many other types of labour activities were also detected, including trafficking for forced labour in agriculture, catering and other industries.

About 76 per cent of the victims trafficked for 'other purposes' are female. This percentage is consistent across all regions where a sufficient number of cases of this type have been detected. In East Asia, for instance, forced marriages seem to be a significant form of exploitation in the Mekong area. In North America, women and girls are trafficked for mixed exploitation, meaning that the same victim is exploited for sex as well as labour purposes. Sham and forced marriages targeting adult women is also a form of trafficking that has been detected in different European countries. Trafficking for begging and adoption, in countries with legislation that includes these as forms of trafficking, tend to include both boys and girls as victims, with slightly more girls than boys. From the limited data available, it seems that trafficking for child pornography and for committing crime may target more boys than girls.

FIG. 10 Gender breakdown of detected victims of trafficking for forced labour, by region, 2014 (or most recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

Forms of trafficking in persons:

wide geographical differences

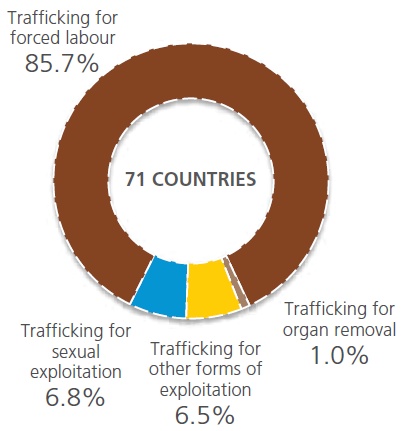

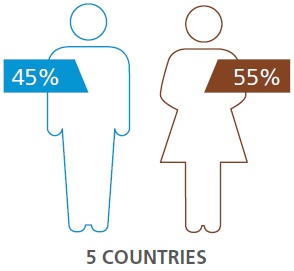

Trafficking for sexual exploitation has been the most commonly detected form as long as UNODC has been collecting data on trafficking in persons. The latest data available - for the 2012-2014 period - is in line with previous years, with about 54 per cent of the 53,700 detected victims having been trafficked for sexual exploitation. The trend for this form, however, is decreasing. Trafficking for forced labour now accounts for a larger share of the detected victims than in 2007.

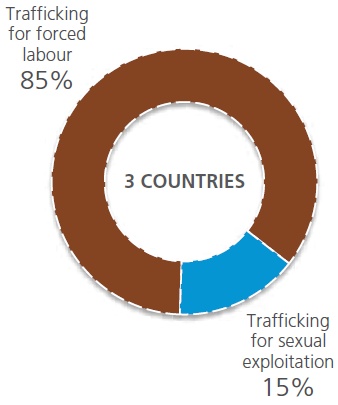

The regional differences observed with regard to the profiles of detected victims are quite pronounced when considering the different forms of trafficking and exploitative purposes. For instance, the large number of men detected in Eastern Europe and Central Asia is connected to the large share of victims trafficked for the purpose of forced labour particularly in Central Asia. About 64 per cent of the victims detected in that region are exploited in different forms of forced labour; the highest level recorded by the reporting countries. There are high levels of trafficking for forced labour in other regions as well, particularly in Africa.

Victims detected in Western and Southern Europe and Central and South-Eastern Europe are largely trafficked for sexual exploitation. Trafficking for forced labour ranges around 20-30 per cent of the total number of detected victims in the countries of this region.

In the Americas, there is a predominance of detected trafficking for sexual exploitation, which is slightly more pronounced in Central America and the Caribbean. North America has a relatively high share of victims trafficked for forced labour; some 40 per cent of the victims detected during the 2012-2014 period. As for South America, about 30 per cent of the detected victims were trafficked for forced labour. Under-reporting of forced labour may be an issue in this region, however, due to differences in trafficking legislation and recording systems in some prominent countries.

FIG. 12 Trends in the forms of exploitation among detected trafficking victims, 2007-2014

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

Trafficking for forced labour is a broad category that includes a large variety of exploitative activities. It occurs across many economic sectors, industries and labour activities. One widely detected form is domestic servitude in households, which has been reported by many countries across the world. But trafficking for forced labour also happens in seasonal agricultural work such as berry picking in Nordic countries, or fruit and vegetable collection in the Mediterranean region. Victims of trafficking for forced labour have been detected in the fishing industry in South-East Asia and Africa, in catering services and restaurants in many countries, in construction and in the cleaning industry. Moreover, victims are also trafficked for forced labour in the mining sector; for example, to mine diamonds in West Africa, or gold and other minerals in Central Africa, to mention some of the many areas in which trafficking victims are exploited.

The Sustainable Development Goals and trafficking in persons

In September 2015, the international community gathered at the United Nations headquarters in New York to decide upon a new, broad development framework to replace the Millennium Development Goals. The vision was of "a world of universal respect for human rights and human dignity, the rule of law, justice, equality and non-discrimination; of respect for race, ethnicity and cultural diversity; and of equal opportunity permitting the full realization of human potential and contributing to shared prosperity. A world which invests in its children and in which every child grows up free from violence and exploitation. A world in which every woman and girl enjoys full gender equality and all legal, social and economic barriers to their empowerment have been removed. A just, equitable, tolerant, open and socially inclusive world in which the needs of the most vulnerable are met."™

To guide global efforts to reach such a world, Heads of State and Government from more than 150 countries announced a set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with 169 associated targets.b The goals and targets will serve as a measurable framework for efforts to achieve this vision by 2030.

SDG 16 calls for the promotion of peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, providing access to justice for all and building effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels. In the context of SDG 16, the international community calls for the end of abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children (SDG Target 16.2). This Target will be measured, among other indicators, by assessing the number of victims of trafficking in persons, disaggregated by age, sex and forms of exploitation (indicator 16.2.2).

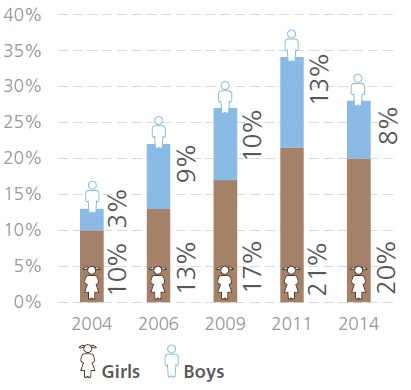

Share of children among detected victimes of trafficking in persons, by gender, 2004-2014

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

Reporting soundly and accurately on indicator 16.2.2 poses a great challenge to the international community. Measuring the total volume of trafficking in persons is not an easy task as any assessment of this crime needs to account for the coexistence of its three defining elements, the act, the means and the purpose. The Global Report is currently the only international source of information on victims of trafficking in persons, detailed by age and sex, and form of exploitation suffered, for a large number of countries (85 for this edition). On the basis of this wealth of information, UNODC can generate some baseline data for indicator 16.2.2. concerning the segment of trafficking victims that are detected. Estimating the number of undetected victims remains a challenge.

The research community and UNODC are investing in the development of new methodologies to estimate the number of undetected victims.c Until the coverage of these estimates allow for accurate global estimates, the indicator on detected victims can be used to inform the achievement of trafficking in persons-related targets to a certain extent. While this indicator clearly doesn't measure the volume of trafficking in persons, it can monitor how certain population groups such as children and girls are over time exposed to trafficking.

Trafficking in persons is also explicitly addressed in Target 5.2 on the elimination of all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation, and in Target 8.7 on taking immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms. The fact that different SDGs make reference to trafficking in persons emphasizes how this is a multifaceted phenomenon, with criminal, violence, human rights, migration, labour and gender connotations.

The data on trafficking in persons regularly collected by UNODC can also be used by Member States to track progress towards the realization of these goals. The statistics on detected victims of trafficking in persons for more than 100 countries around the world, disaggregated by age, sex and forms of exploitation, can help to infer indicator 16.2.2.

For the inaugural report on the SDGs, which takes stock of where the world stands regarding the 2030 targets, UNODC provided this data to help assess the extent of child trafficking. The data showed that the shares of girls and boys among detected victims of human trafficking peaked in 2011 at 21 per cent and 13 per cent, respectively, of the cases detected by authorities that year. More recently, for the year 2014, the share of detected girls among victims of trafficking remained stable at about 20 per cent, while the share of boys decreased to 8 per cent. As a result, the share of child trafficking among the total number of detected victims decreased from 33 to 28 per cent.d

The data collected by UNODC can also be used to monitor different components of Targets 8.7 and 5.2. For Target 5.2, the UNODC data shows that the share of women and girls among detected trafficking victims is approximately 70 per cent, which is a significant reduction from 2004, although there was a minor increase from 2011 to 2014.

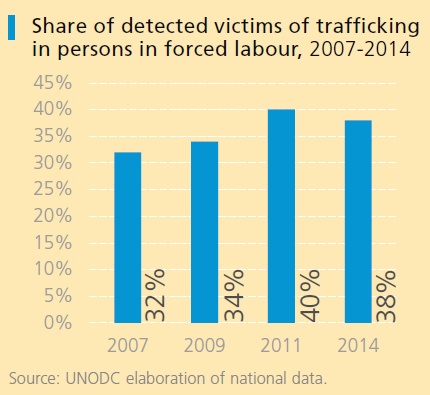

In connection with Target 8.7, the UNODC data indicates that the share of victims of trafficking for forced labour among trafficking victims increased from 32 per cent in 2007 to 40 per cent in 2011. More recently, for 2014, this share remained broadly stable at about 38 per cent.

Share of detected victims of trafficking in persons in forced labour, 2007-2014

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

a. A/RES/70/1, United Nations General Assembly, Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 21 October 2015, para. 8.

b. For a full list, see https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs.

c. In 2016, UNODC conducted a promising pilot Multiple Systems Estimate (MSE) of trafficking in persons victims in the Netherlands to test this particular methodology to estimate the number of victims there. Please refer to the text box (p. 47) with further details about the MSE methodology. For a comprehensive overview, see: UNODC Research Brief (2016). Multiple Systems Estimation for estimating the number of victims of human trafficking across the world (primary authors: J. Van Dijk and P. G. M. van der Heijden).

d. United Nations (2016). Sustainable Development Goals Report 2016 (available at: http://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2016/).

A limited number of cases of trafficking for organ removal were detected during the reporting period, mainly in Central and South-Eastern Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, North Africa and the Middle East, and South America. Some 120 victims of this form of trafficking were detected between 2012 and 2014 in about 10 countries in different parts of the world.

Several 'other' forms of trafficking are also detected and aggregated. These accounted for about 8 per cent of the detected victims between 2012 and 2014. During this period, the following 10 categories of exploitation were reported: trafficking for the purpose of begging, for committing various illegal activities, for forced and sham marriages, for child soldering, for baby selling/illegal adoption, for the production of pornographic material, for human sacrifice, for the removal of body parts, for different combinations of mixed exploitation (for example, sexual exploitation and forced labour in domestic servitude), as well as the trafficking of pregnant women for the purpose of selling their babies.

Begging is the most commonly reported 'other purpose' of exploitation. Nearly 1,000 victims of trafficking in persons for begging were detected in about 20 countries in different regions between 2012 and 2014, accounting for more than 2 per cent of the total number of detected victims.

In many instances, children are targeted for trafficking for the purpose of begging, as is the case of the Talibe' in West Africa or street begging in Europe. Some cases prosecuted by national authorities show that this form of trafficking may also target people with disabilities. In the Republic of Moldova, for example, two persons trafficked an adult with mental health issues from their village to Moscow where the victim was forced to beg on the street under the threat of violence. |23| In Austria, a man with a physical disability was forced to beg by three fellow citizens in the streets of several Austrian cities for four years. The traffickers threatened that if the victim did not collect between 300-500 euros per day, he would be beaten, isolated and deprived of food. |24|

Trafficking in persons for marriage

The UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol contains a list of the minimum forms of exploitation countries should include in their legal framework. This list "... includes exploiting the prostitution of others, sexual exploitation, forced labour, slavery or similar practices and the removal of organs." Although trafficking for sexual exploitation and forced labour remain the most commonly detected forms of trafficking in many parts of the world, trafficking in persons may be conducted for a variety of other purposes as well.

The data collected by UNODC over time yields a list of exploitative forms reported by the national authorities that reflect the innovative ways traffickers operate, and how jurisprudence is enlarging the applicability of the UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol beyond the minimum forms of exploitation listed in the Protocol. One form is trafficking for marriages, which was reported by 15 countries in many parts of the world during the 2012-2014 period.

Trafficking for forced or sham marriages accounts for about 1.4 per cent of the total number of detected victims. This form of trafficking targets only female victims, and it takes on different permutations, from involved organized irregular immigration and benefit fraud schemes in Europe, to traditional practices™ in Central Asia and the Middle East, to the trade of women for marriages in South-East Asia. Vietnamese and Chinese authorities reported court cases that involved trafficking for marriage from rural areas in the north of Viet Nam to China.b Cases referred to include that of a Chinese man who engaged Vietnamese persons with local knowledge to find girls for marriages in China at the price of 10,000 yuan (approximately US$ 1,500) for each girl recruited. The recruiters then moved the victims across the border into Chinese territory where the victims were sold for marriage for the agreed-upon price. Some cases of forced child marriage involve relatives of the victims, like the case of a 14-year-old girl in South Africa. The teenager was forced by her grandmother and uncle to marry a 35-year-old man.c

Although many sham marriages do not involve trafficking in persons,d some do. A different mode of trafficking has surfaced in the form of a large transnational organized crime group that recruited Central European women for sham marriages in Western Europe. In Latvia, an extensive criminal proceeding saw many offenders investigated and several women recognized as victims. Sham marriages were used to give Asian men the possibility of obtaining a residence permit for the European Union. Many of the victims had some form of emotional or behavioural disorder, which contributed to their vulnerability to coercion or fraud. Once they arrived in their destination country, the victims were locked in apartments, raped and abused physically and psychologically to obtain their consent to marriage. After marriage, they were treated as if they were the property of their 'husbands' and the abuse continued.e

™ Such practices involve marriages without the consent of the woman or child marriages. These practices may involve abduction or parents selling or forcing the daughter to marry.

b One case provided by Viet Nam, which concluded with convictions by the court of appeal of the supreme people's court, and sentences that ranged from 5 to 7 years of imprisonment. Another case, also provided by Viet Nam, concluded with convictions by the court of Yen Binh province, and 8-year prison sentences. Case provided by China which concluded with convictions by the Supreme People's Court. The two traffickers received sentences of 11 years and 9 months, and 7 years and 9 months.

c Case provided by South Africa, which concluded with a conviction by the court of Western Cape Town to 25 years of imprisonment.

d See, for example, European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control (HEUNI) (2016). Exploitative sham marriages: exploring the links between human trafficking and sham marriages in Estonia, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania and Slovakia.

e Case provided by Latvia which is still under investigation.

Trafficking for the commission of illegal activity has also been reported, although it is a difficult form to detect. Cases of children and adults exploited in the cultivation of cannabis, trafficked for shoplifting, for theft and other forms have been reported in countries in Europe and Central Asia, South America and Africa. About 1 per cent of the total number of detected victims in 13 countries were trafficked for the commission of illegal activity.

Examples of these different forms of trafficking can be found in court cases. Two victims from Poland, for example, were trafficked to Sweden using false promises of residency in the destination country and work in the construction sector. Once at destination, the victims were forced to shoplift and subjected to violence and threats. Eventually, the victims managed to escape and return to Poland. |25| Similarly, in Norway, the authorities reported a case of two traffickers who recruited victims in Romania to exploit them in Norway by making them steal petrol and beg under constant life threats. One of the traffickers was arrested in an attempt to bring another two victims from Romania to Norway. |26|

Other forms of trafficking detected during the reporting period included trafficking for the purpose of child soldiering, which is mainly detected in conflict and post-conflict countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East (and discussed further in Chapter 2). Baby selling and illegal adoption - in countries that consider these to be forms of trafficking in persons - have been reported in Europe, Africa, Central and South America, Central Asia and East Asia. Trafficking for the purpose of human sacrifice and removal of body parts has been reported in some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Trafficking for the production of pornographic material was reported by a few countries in South-Eastern Europe, South America, the Middle East and Eastern Europe.

Trafficking for mixed exploitation has been reported by a limited number of countries, usually combining forced labour and sexual exploitation. In the Dominican Republic, for example, teenage girls were forced to wait tables in a bar and to have sexual relations with the bar's customers. |27| A similar case took place in Mexico, where a 17-year-old girl who had left home due to family problems became an easy target for traffickers. She was exploited as a waitress in a bar and was also forced to have sexual relations with clients, while her earnings were withheld by the bar owners. |28| Another type of mixed exploitation found in the case files was domestic servitude combined with sex slavery. In South Africa, a man asked his female worker to recruit young girls to work for him. The woman recruited three teenage girls from Mozambique, and the man exploited them sexually and for forced labour. |29|

In addition, for about 1 per cent of the victims detected and reported to UNODC during the 2012-2014 period, the form of exploitation could not be established, either because the victim was detected before the exploitation took place or because the form was not recorded. These victims were not considered in the above analysis.

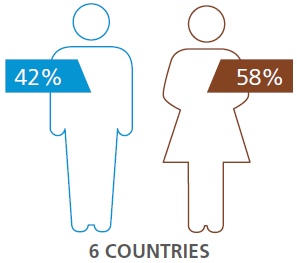

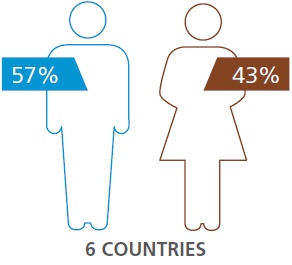

Profile of the traffickers

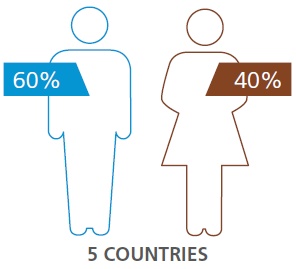

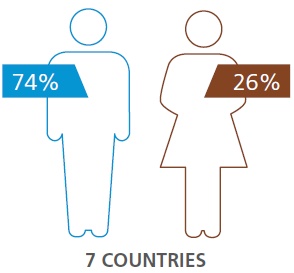

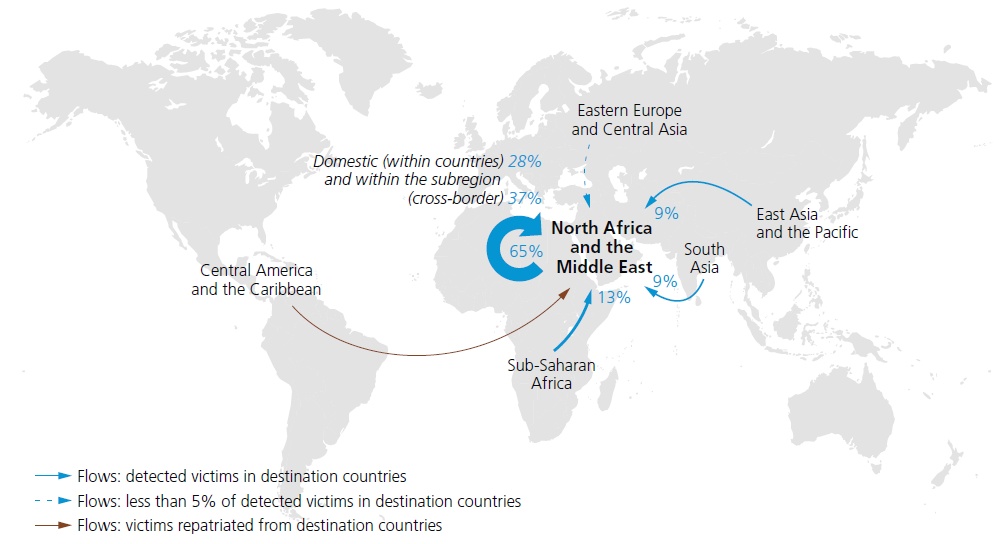

Most traffickers are male...

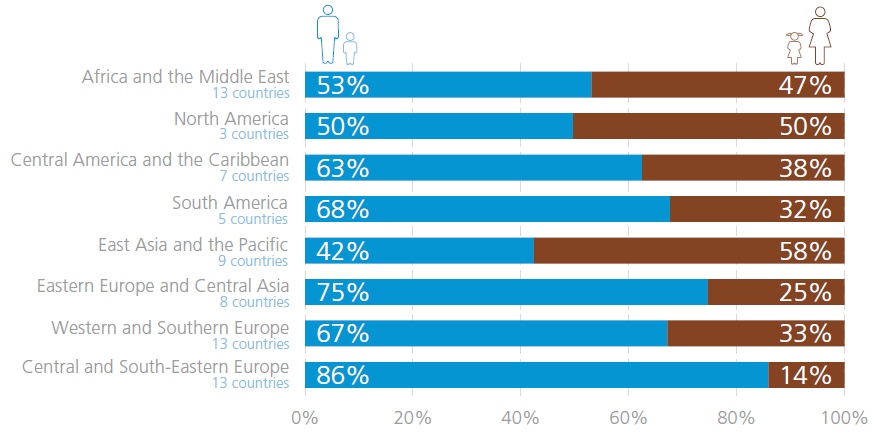

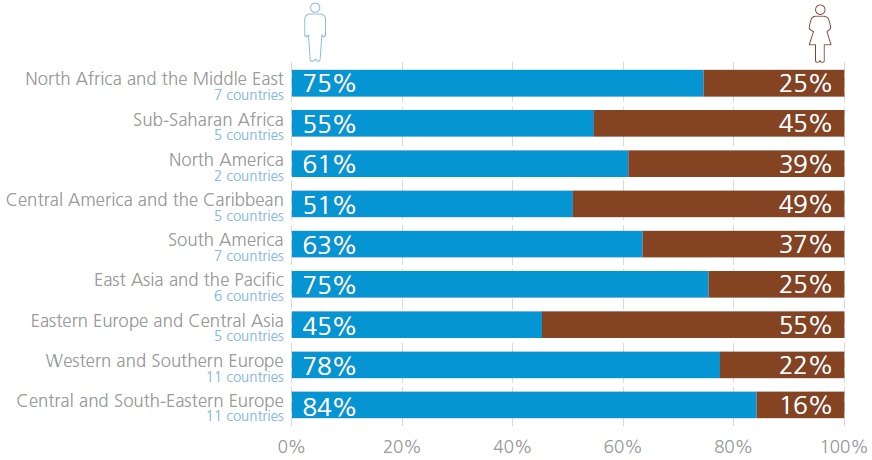

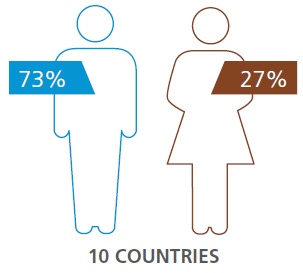

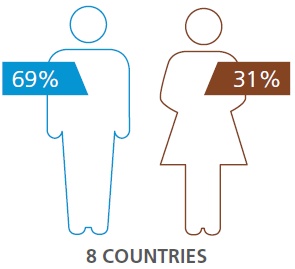

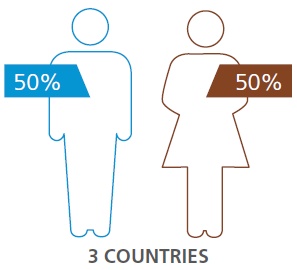

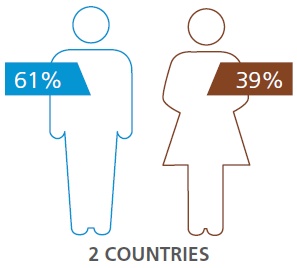

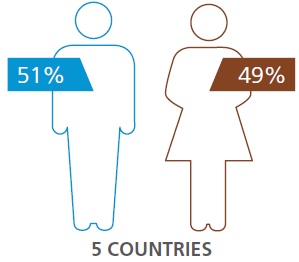

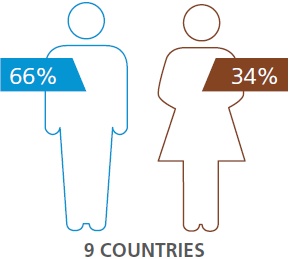

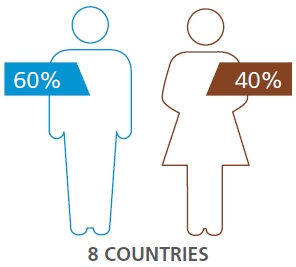

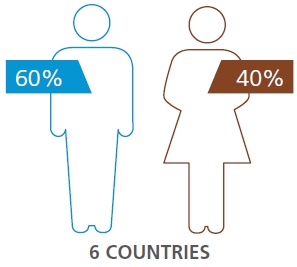

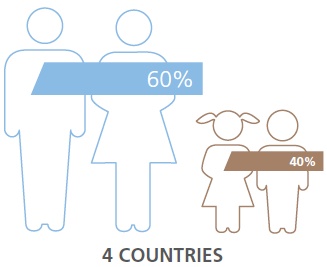

As for nearly every other crime, most trafficking in persons offenders are male. Roughly 6 in 10 offenders are male across all stages of the criminal justice process. Even so, the significant share of women offenders is remarkable, as there are few crimes with such high levels of female participation. |30|

The broad pattern of more male than female offenders holds true across most regions and subregions as well. While the exact shares vary, nearly every area reports more male offenders. One notable exception is Eastern Europe and Central Asia, where the gender profiles of traffickers (and victims) is the opposite of those seen in other areas. The majority of offenders in that region are women.

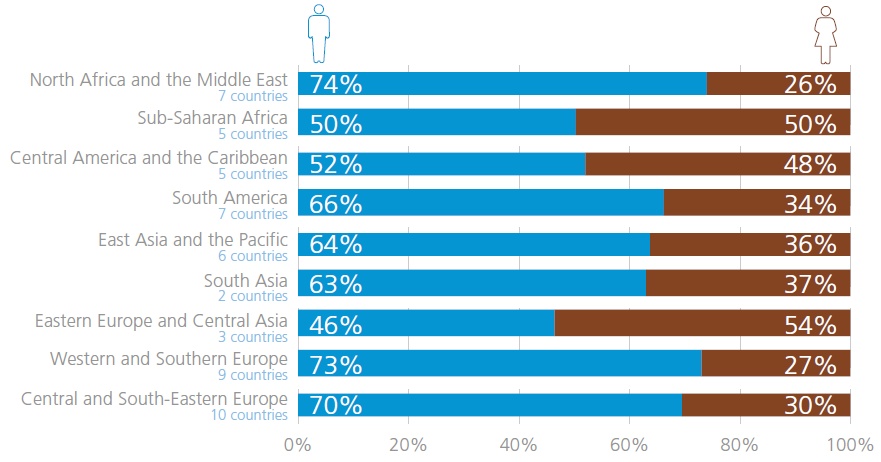

FIG. 14 Persons investigated for trafficked in persons, by sex and region, 2014 (or most recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

FIG. 15 Persons prosecuted for trafficked in persons, by sex and region, 2014 (or most recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

Looking at the profiles of persons investigated for trafficking in persons, most countries investigate more men than women. The shares are broadly similar for prosecutions.

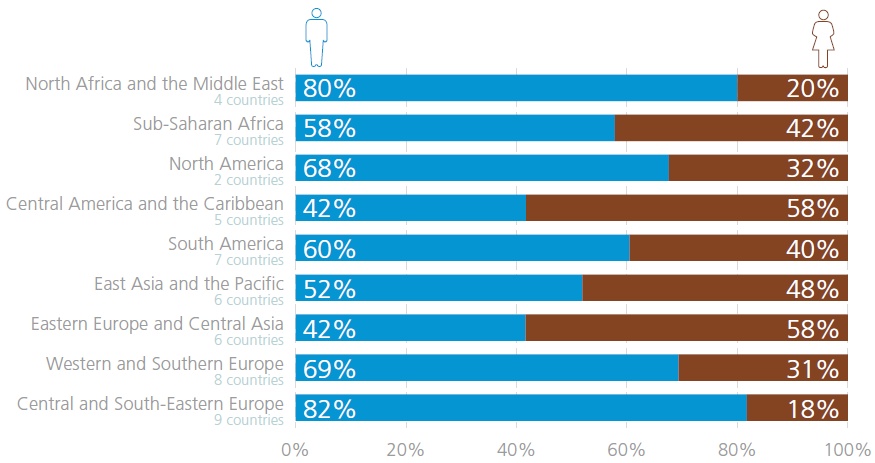

Out of the approximately 6,800 persons who were convicted of trafficking in persons during the years 2012-2014 in the available data, about 60 per cent were male. The gender breakdown by geographical area is similar to that seen for investigations and prosecutions. Central and South-Eastern Europe, Western and Southern Europe, East Asia and the Pacific, and North Africa and the Middle East all convict more than 70 per cent males of trafficking in persons; in Central and South-Eastern Europe, the share is larger than 80 per cent.

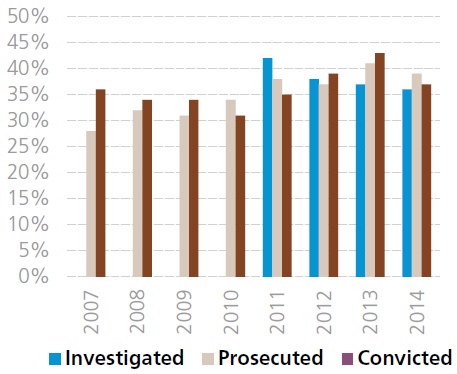

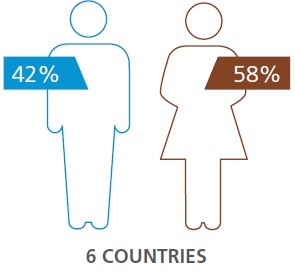

...but the share of female offenders is increasing

Although the majority of offenders are male, the detected female involvement in the crime of trafficking in persons is remarkably high, compared to other crimes. This is true across all stages of the criminal justice process. The share of females involved in trafficking crimes has remained broadly stable at a high level over the past few years, with some variations between investigations, prosecutions and convictions.

The data for investigations, disaggregated by gender, only goes back to 2011. It appears that there has been a slight decrease in the share of women among those investigated for trafficking offences since then. The data for prosecutions, however, which goes back to 2007, shows a steady increase, as does the data for convictions. In 2014, women comprised well over a third of all offenders at all three criminal justice stages. Previous UNODC research on many types of crime in a large number of countries has found that women typically comprise less than 15 per cent of offenders. |31|

Looking more specifically at the role of women in trafficking crimes, a statistical correlation published in the Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2012 suggested that adult women were more involved in the trafficking of young girls. Moreover, qualitative studies indicate that girl victims are frequently recruited or guarded by older women. |32| The 2014 Global Report presented a qualitative analysis that suggested that women in organized criminal networks participated more in lower-ranking activities -the recruitment of victims, in particular - while men tended to engage in organizational or exploitation roles. |33| Research conducted on trafficking in persons case law indicated that female traffickers were involved in 54 per cent of the 155 cases examined for the study. Women worked either alone or with other women in 21 per cent of the cases, often playing leading roles and trafficking large numbers of other women for sexual exploitation. In the rest of the cases (33 per cent), women worked together with male traffickers. |34|

FIG. 17 Persons convicted of trafficking in persons, by sex and region, 2014 (or most recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

FIG. 18 Trends in the shares of females among persons investigated, prosecuted or convicted of trafficking in persons, 2007-2014

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

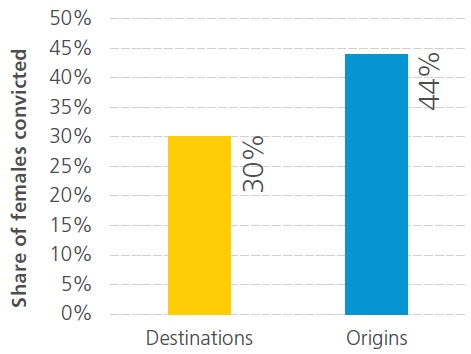

Women traffickers are more likely to be convicted in countries of origin. While destination countries reported an average 30 per cent share of convicted female traffickers in the period 2012-2014, the corresponding share in origin countries was 44 per cent. |35|

It appears that among traffickers who are not engaged in a criminal organization and who are operating in predominantly domestic trafficking flows, two typologies of operation are common. One of these types is trafficking carried out by couples, either a husband/wife or girlfriend/boyfriend, who recruit and exploit victims together. The other common type sees victims being recruited by family members of both genders. In these cases, male and female offenders are more or less equally represented.

Court cases can shed light on these types of trafficking. For example, in Armenia, a couple convinced two girls to move to the Russian Federation, with the purpose of sexually exploiting them. Both the traffickers and the victims lived in an Armenian city near the Russian border. One of the two victims refused to leave while the other was exploited for two weeks in a Russian village. |36| Similar cases involved a Romanian couple sexually exploiting a Romanian girl for about six months in Denmark, |37| and a Tajik couple recruiting girls from Tajikistan to be exploited in the Middle East. |38| In all these cases, women played a major role in the recruitment of victims. Perhaps the facade of a 'stable couple' is more reassuring for the targeted victims (or their parents) than a single male recruiter.

Another recurring element in cases of convicted female traffickers is the prevalence of former victims becoming perpetrators. Victims of trafficking in persons have been forced to commit criminal activities such as drug trafficking or shoplifting, but trafficking victims may also be forced to recruit other victims of trafficking in persons. There is evidence that, particularly in the field of trafficking for sexual exploitation, many former victims are at some point offered the opportunity of recruiting new victims or serving as a 'madam.' |39| Victims' motivation to switch to such roles may be to reduce their debt to traffickers or others, or to end their own exploitation.

Traffickers may benefit from this arrangement as well, as they have a new way to reach additional victims. Moreover, once victims are engaged in the enterprise, they become accomplices to the trafficking operation and are then less likely to cooperate with law enforcement. |40| For example, in Argentina, a structured criminal group trafficked many women and girls for sexual exploitation from the Dominican Republic. The group used Dominican women who were previously exploited for years in Argentina to recruit other victims back home. The recruiters used deception regarding the working activities to gain the victims' consent. In this case, the court recognized that the recruiters were previous victims of trafficking who were subsequently used by the criminal group to recruit other women. |41|

This is not to suggest that women convicted of trafficking in persons were all victims at some point, or that women are only represented in low-level positions within large, complex trafficking rings. In fact, court cases have also shown that some large trafficking rings are female-led. In one case, three women recruited girls from the Russian Federation to be sold to other traffickers operating in the Middle East. |42| In another, a more transnational organized criminal group was led by a Russian woman. The group was divided into two branches; the first was in charge of recruiting and transporting girls, whereas the second was in charge of exploiting them. The group was very well structured and involved at least nine members in addition to the leader. At least 13 victims were trafficked for the purpose of sexual exploitation by this group. |43| In a third case from the Russian Federation, another well organized transnational group of five people - led by a woman -exploited at least 25 women and two girls. |44|

In other cases involving female-led trafficking rings, the groups were more improvised, but nonetheless managed to traffic many victims. In Azerbaijan, for example, two sisters were convicted of organizing a criminal network that trafficked at least nine women into other countries. |45| Similarly, in Canada, a group of three underage girls beat, drugged and forced other girls into sexual exploitation. Seven Canadian girls were identified as victims. |46|

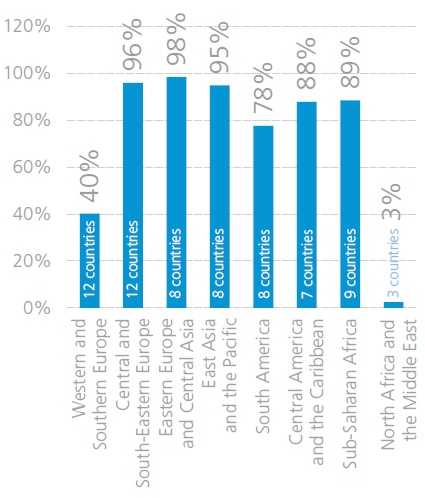

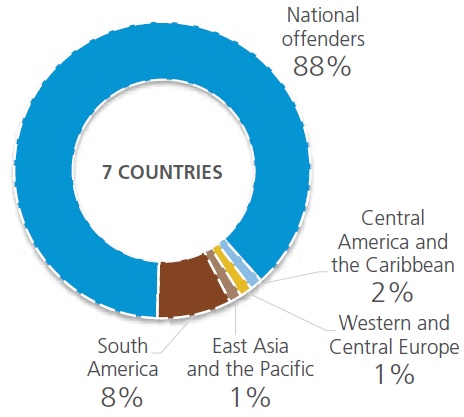

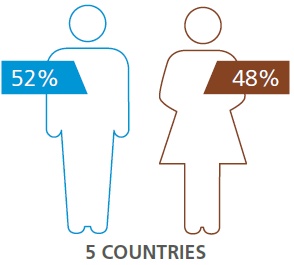

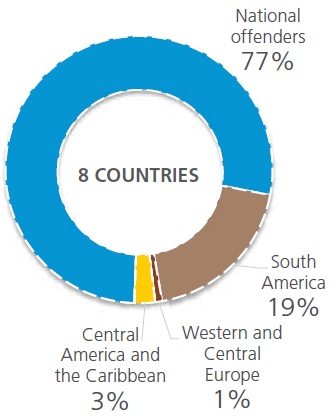

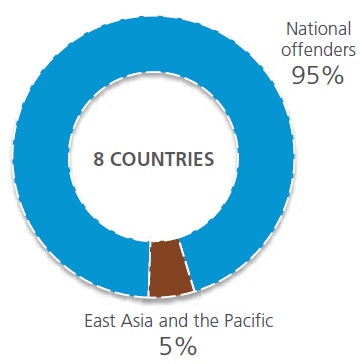

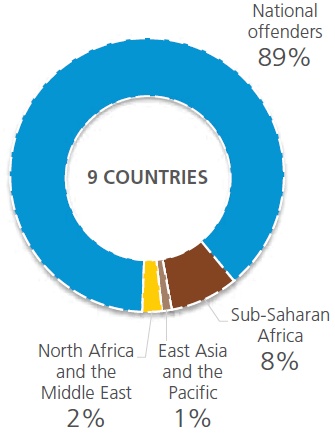

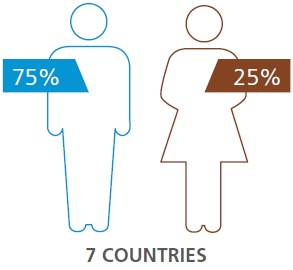

Trafficking in persons largely involves national traffickers

In the countries for which data was available, on average, about three quarters of the convicted offenders were citizens of the country in which they were convicted during the 2012-2014 period. The remaining offenders - foreigners in the country of conviction – were near-equally split between citizens of countries within and outside the region where they were convicted.

FIG. 20 Shares of national and foreign citizens among convicted traffickers (relative to the country of conviction), 2014 (or most recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

FIG. 21 Shares of traffickers convicted in their country of citizenship, by region, 2014 (or most recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration of national data.

The regional aggregations reflect the global average, with two exceptions. In Western and Southern Europe, foreign citizens accounted for 60 per cent of the convicted offenders, and in the Middle East, nearly all the persons convicted of trafficking in persons were foreigners.

The distinction between countries of origin and destination of cross-border trafficking has a bearing on the gender profile of convicted traffickers. The same is true – and even more so - for the citizenships of offenders. Nearly all (97 per cent) convicted traffickers in countries of origin of cross-border trafficking are citizens of the convicting country. In countries of destination, however, convicted traffickers are both own citizens and foreigners, more or less equally distributed.

Moreover, a closer look at the citizenships of foreigners convicted of trafficking in persons in destination countries reveals a general pattern. The citizenships of these offenders broadly mirror the citizenships of the victims detected there, as presented in the 2014 Global Report. |47| In other words, the nationality profiles of offenders are closely connected to the profiles of the victims they traffic. Sharing a culture and/or language background could lead victims to more readily trust citizens of their own country when discussing 'opportunities' abroad. This might be particularly pronounced in the case of women recruiting other women.

An Australian court case illustrates the ways that this trust, and the fear associated with an irregular move to another country, are used by traffickers. In this case, a Thai girl was coerced into exploitation by a Thai woman who had promised the girl a better future in Australia. Once there, the girl was sexually exploited under the threat of being reported to the authorities as an irregular migrant and deported back to Thailand. |48| A large number of cases of this sort have been reported by various national authorities, often involving victims that are not willing or ready to cooperate in the criminal justice process because they still trust their co-national traffickers, while at the same time fearing the authorities.

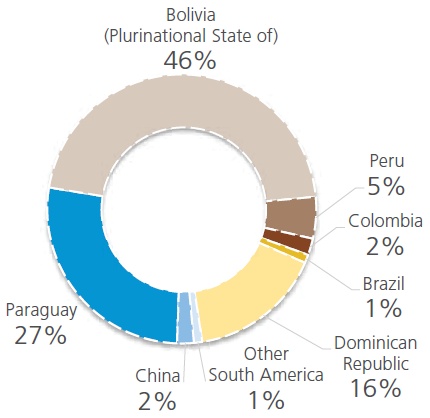

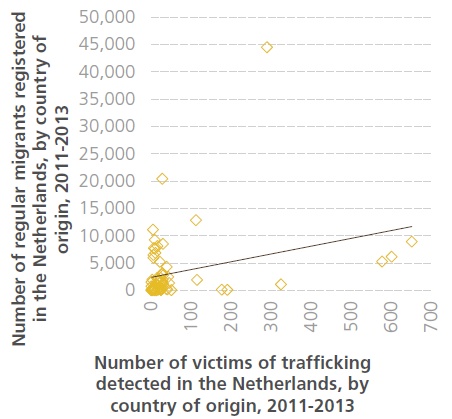

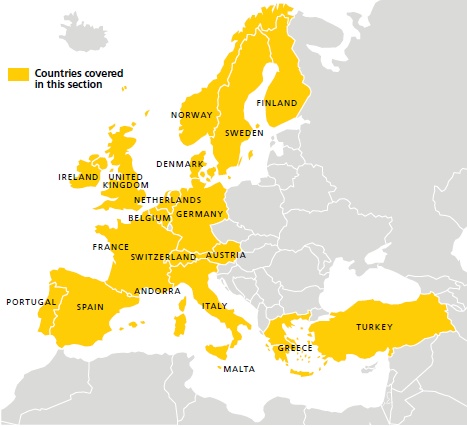

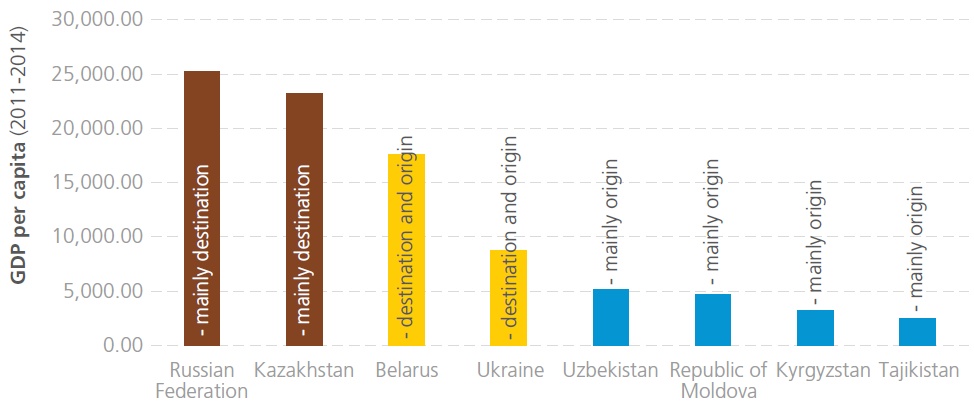

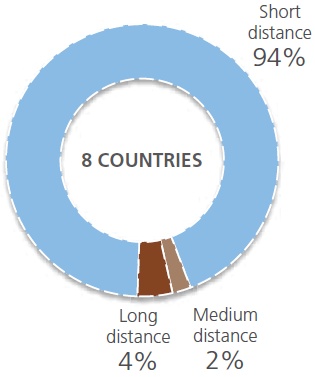

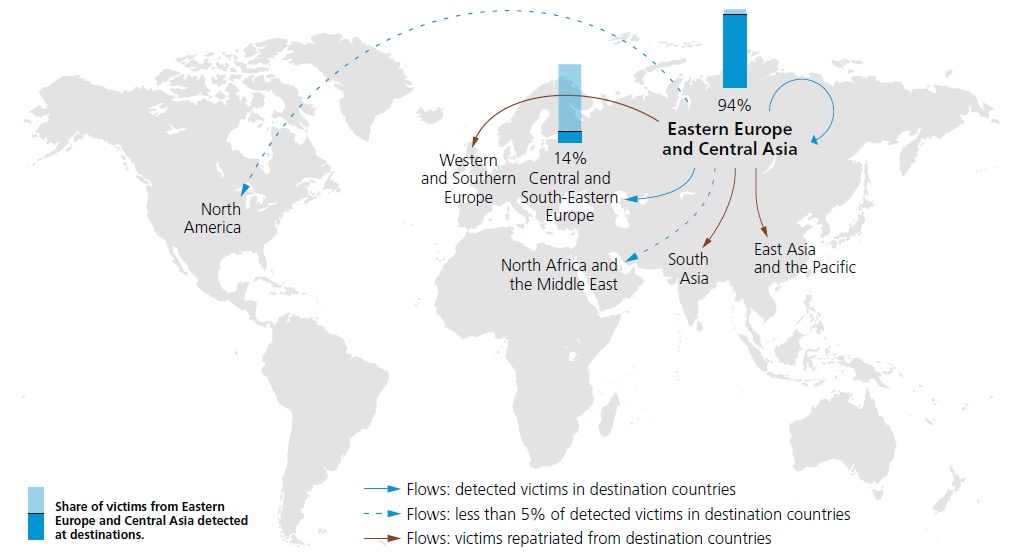

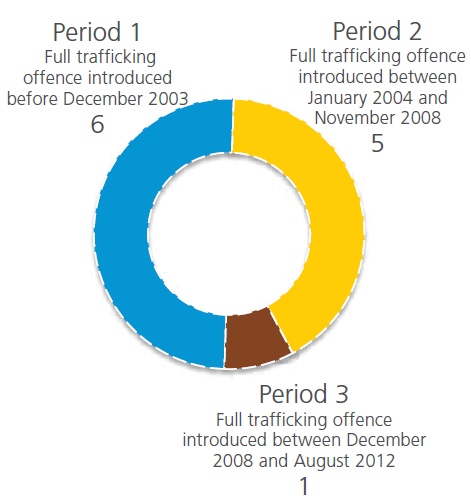

Cases have also been reported where victims have been recruited in their own country by foreigners, even if such cases are relatively rare. In Argentina, two cases involved Argentine citizens crossing the border into Paraguay to recruit young women for sexual exploitation in Argentina. At least 4 victims were identified. |49| In Portugal, a Portuguese national trafficked Brazilian women into sexual exploitation there. The victims were lured into a debt bondage scheme connected with the 'migration fee' the victims had to pay for the travel from Brazil to Portugal, plus additional costs, as is normal practice in this criminal modus operandi. |50| In all these cases, traffickers and victims shared a common language, which is an element that may serve to link the persons involved in the crime - offenders and victims – even if their citizenships differ.