| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

08Nov13

Multilateral Development Banks: Overview and Issues for Congress

Contents

Overview of the Multilateral Development Banks

Historical Background

World Bank

Operations: Financial Assistance to Developing Countries

Regional Development BanksFinancial Assistance Over Time

Funding: Donor Commitments and Contributions

Recipients of MDB Financial AssistanceNon-Concessional Lending Windows

Structure and Organization

Concessional Lending WindowsRelation to Other International Institutions

Debates about Effectiveness of the MDBs

Internal Organization and U.S. RepresentationEffectiveness of Foreign Aid

Bilateral vs. Multilateral AidAuthorizing and Appropriating U.S. Contributions to the MDBs

Congressional Oversight of U.S. Participation in the MDBs

U.S. Commercial Interest in the MDBsFigures

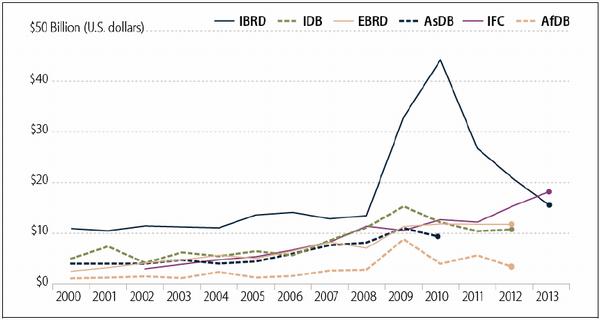

Figure 1. MDB Non-Concessional Financial Assistance, 2000-Present

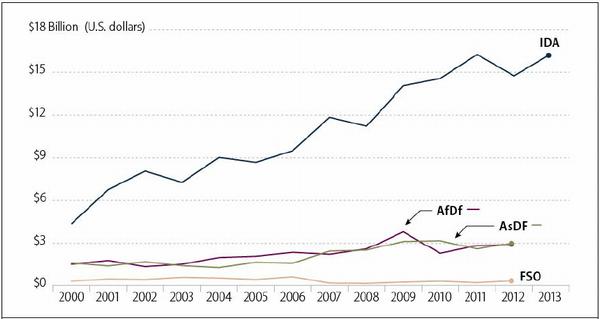

Figure 2. MDB Concessional Financial Assistance,

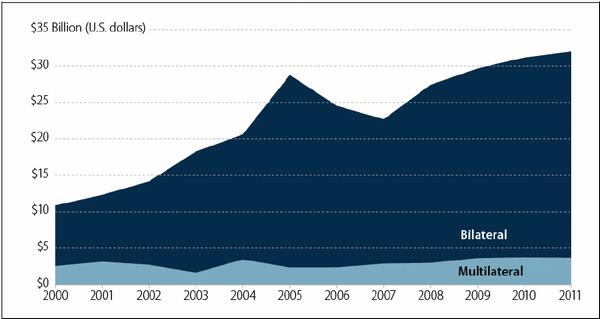

Figure 3. U.S. Bilateral and Multilateral Official Development Assistance, 2000-PresentTables

Table 1. Overview of MDB Lending Windows

Table 2. MDB Financial Assistance: Top 10 Recipients

Table 3. MDB Non-Concessional Lending Windows: U.S. Financial Commitments

Table 4. MDB Non-Concessional Lending Windows: Top Donors

Table 5. MDB Concessional Lending Windows: Cumulative U.S. Contributions

Table 6. MDB Concessional Lending Windows: Top Donors

Table 7. U.S. Executive Directors

Table 8. U.S. Voting Power in the MDBs

Summary

The multilateral development banks (MDBs) include the World Bank and four smaller regional development banks: the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Asian Development Bank (AsDB), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). The United States is a member of, and major donor to, each of the MDBs.

The MDBs provide financial assistance to developing countries in order to promote economic and social development. They primarily fund large infrastructure and other development projects and, increasingly, provide loans tied to policy reforms by the government. The MDBs provide non-concessional financial assistance to middle-income countries and some creditworthy low-income countries on market-based terms. They also provide concessional assistance, including grants and loans at below-market rate interest rates, to low-income countries.

Critics argue that the MDBs focus on "getting money out the door" (rather than delivering results), are not transparent, and lack a clear division of labor. They also argue that providing aid multilaterally relinquishes U.S. control over where and how the money is spent. Proponents argue that providing assistance to developing countries is the "right" thing to do and has been successful in helping developing countries make strides in health and education over the past four decades. They also argue that MDB assistance is important for leveraging funds from bilateral donors, promoting policy reforms, and enhancing U.S. leadership.

The Role of Congress in the MDBs

- Funding: Congressional legislation is required for the United States to make financial contributions to the MDBs. Appropriations for the concessional windows occur regularly, but appropriations are far more infrequent for the non-concessional windows. Unusually, all the MDBs are in the process of increasing the size of their non-concessional lending facilities. Congress authorized U.S. contributions to the "general capital increases" of the non-concessional lending windows in FY2011 for the AsDB and in FY2012 for the other MDBs. The appropriations for these increases are expected to be spread out over a five- to eight-year period, depending on the institution.

- Oversight: In addition to congressional hearings on the MDBs, Congress exercises oversight over U.S. participation in the MDBs through legislative mandates. These mandates direct the U.S. Executive Directors to the MDBs to advocate certain policies and how to vote on various issues at the MDBs. Congress also issues reporting requirements for the Treasury Department on issues related to MDB activities. Congress can also withhold funding for the MDBs unless certain institutional reforms are met ("power of the purse").

- U.S. Commercial Interests: Billions of dollars in contracts are awarded each year to complete projects financed by the MDBs. Some of these contracts are awarded to U.S. companies. The World Bank has been discussing major changes in how companies bid on World Bank projects, and this could be an area that Congress may want to monitor.

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) are international institutions that provide financial assistance, typically in the form of loans and grants, to developing countries in order to promote economic and social development. The term MDBs typically refers to the World Bank and four smaller regional development banks:

- the African Development Bank (AfDB);

- the Asian Development Bank (AsDB);

- the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD); and

- the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). |1|

The United States is a member of each of these institutions. Congress plays an important role in determining U.S. funding for the MDBs and engaging in oversight of the Administration's participation in the MDBs.

This report provides an overview of the MDBs and highlights major issues for Congress. The first section discusses how the MDBs operate, including the history of the MDBs, their operations and organizational structure, and the effectiveness of MDB financial assistance. The second section discusses the role of Congress in the MDBs, including congressional legislation authorizing and appropriating U.S. contributions to the MDBs; congressional oversight; and U.S. commercial interests in the MDBs.

Overview of the Multilateral Development Banks

The MDBs provide financial assistance to developing countries, typically in the form of loans and grants, for investment projects and policy-based loans. Project loans include large infrastructure projects, such as highways, power plants, port facilities, and dams, as well as social projects, including health and education initiatives. Policy-based loans provide governments with financing in exchange for agreement by the borrower country government that it will undertake particular policy reforms, such as the privatization of state-owned industries or reform in agriculture or electricity sector policies. Policy-based loans can also provide budgetary support to developing country governments. In order for the disbursement of a policy-based loan to continue, the borrower must implement the specified economic or financial policies. Some have expressed concern over the increasing budgetary support provided to developing countries by the MDBs. Traditionally, this type of support has been provided by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Most of the MDBs have two funds, often called lending windows or lending facilities. One type of lending window is used to provide financial assistance on market-based terms, typically in the form of loans, but also through equity investments and loan guarantees. |2| Non-concessional assistance is, depending on the MDB, extended to middle-income governments, some creditworthy low-income governments, and private sector firms in developing countries. |3| The other type of lending window is used to provide financial assistance at below market-based terms (concessional assistance), typically in the form of loans at below-market interest rates and grants, to governments of low-income countries.

The World Bank is the oldest and largest of the MDBs. The World Bank Group comprises three sub-institutions that make loans and grants to developing countries: the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the International Development Association (IDA), and the International Finance Corporation (IFC). |4|

The 1944 Bretton Woods Conference led to the establishment of the World Bank, the IMF, and the institution that would eventually become the World Trade Organization (WTO). The IBRD was the first World Bank affiliate created, when its Articles of Agreement became effective in 1945 with the signatures of 28 member governments. Today, the IBRD has near universal membership with 187 member nations. Only Cuba and North Korea, and a few micro-states such as the Vatican, Monaco, and Andorra, are non-members. The IBRD lends mainly to the governments of middle-income countries at market-based interest rates.

In 1960, at the suggestion of the United States, IDA was created to make concessional loans (with low interest rates and long repayment periods) to the poorest countries. IDA also now provides grants to these countries. The IFC was created in 1955 to extend loans and equity investments to private firms in developing countries. The World Bank initially focused on providing financing for large infrastructure projects. Over time, this has broadened to also include social projects and policy-based loans.

Inter-American Development Bank

The IDB was created in 1959 in response to a strong desire by Latin American countries for a bank that would be attentive to their needs, as well as U.S. concerns about the spread of communism in Latin America. |5| Consequently, the IDB has tended to focus more on social projects than large infrastructure projects, although the IDB began lending for infrastructure projects as well in the 1970s. From its founding, the IDB has had both non-concessional and concessional lending windows. The IDB's concessional lending window is called the Fund for Special Operations (FSO). The IDB Group also includes the Inter-American Investment Corporation (IIC) and the Multilateral Investment Fund (MIF), which extend loans to private sector firms in developing countries, much like the World Bank's IFC.

African Development Bank

The AfDB was created in 1964 and was for nearly two decades an African-only institution, reflecting the desire of African governments to promote stronger unity and cooperation among the countries of their region. In 1973, the AfDB created a concessional lending window, the African Development Fund (AfDF), to which non-regional countries could become members and contribute. The U.S. joined the AfDF in 1976. In 1982, membership in the AfDB non-concessional lending window was officially opened to non-regional members. The AfDB makes loans to private sector firms through its non-concessional window and does not have a separate fund specifically for financing private sector projects with a development focus in the region.

Asian Development Bank

The AsDB was created in 1966 to promote regional cooperation. Similar to the World Bank, and unlike the IDB, the AsDB's original mandate focused on large infrastructure projects, rather than social projects or direct poverty alleviation. The AsDB's concessional lending facility, the Asian Development Fund (AsDF), was created in 1973. Like the AfDF, the AsDB does not have a separate fund specifically for financing private sector projects, and makes loans to private sector firms in the region through its non-concessional window.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

The EBRD is the youngest MDB, founded in 1991. The motivation for creating the EBRD was to ease the transition of the former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and the former Soviet Union from planned economies to free-market economies. The EBRD differs from the other regional banks in two fundamental ways. First, the EBRD has an explicitly political mandate: to support democracy-building activities. Second, the EBRD does not have a concessional loan window. The EBRD's financial assistance is heavily targeted on the private sector, although the EBRD does also extend some loans to governments in CEE and the former Soviet Union.

Table 1 summarizes the different lending windows for the MDBs, noting what types of financial assistance they provide, who they lend to, when they were founded, and how much financial assistance they committed to developing countries in 2012 or FY2013. |6| The World Bank Group accounted for more than half of total MDB financial assistance commitments to developing countries in 2012 or FY2013. |7| Also, about three-quarters of the financial assistance provided by the MDBs to developing countries was on non-concessional terms during those years.

Table 1. Overview of MDB Lending Windows

MDB Type of Financing Type of Borrower Year Founded New Commitments, 2012 or FY2013 (Billion $) World Bank Group International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) Non-concessional loans and loan guarantees Primarily middle-income governments, also some creditworthy low-income countries 1994 15.25 International Development Association (IDA) Concessional loans and grants Low-income governments 1960 16.30 International Finance Corporation (IFC) Non-concessional loans, equity investments, and loan guarantees Private sector firms in developing countries (middle- and low-income countries) 1956 18.3 African Development Bank (AfDB) Non-concessional loans, equity investments, and loan guarantees Middle-income governments, some creditworthy low-income governments, and private sector firms in the region 1964 3.2 African Development Fund (AfDF) Concessional loans and grants Low-income governments in the region 1972 2.9 Asian Development Bank (AsDB)

Non-concessional loans, equity investments, and loan guarantees Middle-income governments, some creditworthy low-income governments, and private sector firms in the region 1966 10.1 Asian Development Fund (AsDF) Concessional loans and grants Low-income governments in the region 1973 3.0 European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) Non-concessional loans equity investments, and loan guarantees Primarily private sector firms in developing countries in the region, also developing-country governments in the region 1991 11.8 Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) Non-concessional loans and loan guarantees Middle-income governments, some creditworthy low-income governments, and private sector firms in the region 1959 10.80 Fund for Special Operations (FSO) Concessional loans Low-income governments in the region 1959 0.32 Source: MDB Annual Reports. World Bank data is for FY20I3 (July - June). Regional development bank data is for 2012 (calendar year). Most of the MDBs also have additional funds that they administer, typically funded by a specific donor and/or targeted towards narrowly defined projects. These special funds tend to be small in value and are not included in this table.

Operations: Financial Assistance to Developing Countries

Financial Assistance Over Time

Figure 1 shows non-concessional MDB financial commitments to developing countries since 2000. As a whole, non-concessional MDB financial assistance was relatively stable in nominal terms until the global financial crisis prompted major member countries to press for increased financial assistance. In response to the financial crisis and at the urging of its major member countries, the IBRD dramatically increased lending FY2008 and FY2009. Regional development banks also had substantial upticks in lending between 2008 and 2009. MDB non-concessional assistance, particularly by the IBRD, has started to fall to pre-crisis levels as the financial crisis has stabilized.

Figure 1. MDB Non-Concessional Financial Assistance, 2000-Present

Source: MDB Annual Reports.

Notes: AsDB data is loans only (does not include other financial assistance such as equity investments or credit guarantees funded out of ordinary capital resources).Figure 2 shows concessional financial assistance provided by the MDBs to developing countries since 2000. The World Bank's concessional lending arm, IDA, has grown steadily over the decade in nominal terms, while the regional development bank concessional lending facilities, by contrast, have remained relatively stable in nominal terms.

Figure 2. MDB Concessional Financial Assistance, 2000-Present

Source: MDB Annual Reports.

Recipients of MDB Financial Assistance

Table 2 lists the top recipients of MDB financial assistance in FY2013 (for the World Bank) and 2012 (for the regional development banks). The table shows that several large, emerging economies, including the "BRICS" (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), receive a steady flow of financial assistance from the non-concessional lending windows of the MDBs. For example, at least one of the BRIC countries is among the top five recipients of financial assistance from the IBRD, the IFC, the AfDB, the AsDB, the EBRD, and the IDB in 2012 or FY2013.

Table 2. MDB Financial Assistance: Top 10 Recipients

(New commitments, Million US$)

World Bank, FY2013 African Development Bank, 2012 IBRD IDA IFC AfDB Groupa Brazil 3,076 Vietnam 1,982 Brazil 1,467 Multinational 1,248 Indonesia 1,721 Bangladesh 1,567 Mexico 1,328 Morocco 1,159 China 1,540 Africa (regional) 1,470 World Region 1,276 Tunisia 545 Poland 1,308 Ethiopia 1,115 China 1,050 South Africa 420 Turkey 1,301 Nigeria 1,015 Turkey 985 Ghana 259 Colombia 600 India 948 Nigeria 974 Ethiopia 255 Morocco 593 Pakistan 744 India 943 Tanzania 237 Egypt 585 Kenya 615 Russia 819 Gabon 223 Tunisia 500 Tanzania 607 Vietnam 805 Ivory Coast 160 Ukraine 460 Dem. Rep. of Congo 532 Bangladesh 573 Uganda 103 Asian Development Bank, 2012 European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2012 Inter-American Development Bank, 2012 AsDB AsDF EBRD IDB Groupb India 2,418 Bangladesh 658 Russia 3,407 Brazil 2,009 China 1,809 Vietnam 463 Turkey 1,384 Mexico 1,519 Indonesia 1,233 Afghanistan 376 Ukraine 1,232 Argentina 1,390 Vietnam 822 Cambodia 275 Poland 887 Costa Rica 700 Philippines 775 Uzbekistan 232 Romania 807 Uruguay 629 Uzbekistan 644 Sri Lanka 152 Mongolia 553 Panama 528 Kazakhstan 496 Laos 140 Kazakhstan 493 Colombia 515 Bangladesh 435 Nepal 104 Serbia 355 Venezuela 400 Pakistan 343 Tajikistan 100 Bulgaria 325 Regional 400 Regional 340 Kyrgyz Republic 95 Croatia 277 Ecuador 365 Source: MDB Annual Reports.

Notes: Data is for commitments and approvals of new financial assistance project, not disbursements of financial assistance.

a. Approvals for the whole African Development Bank Group, which includes the African Development Bank (non-concessional financial assistance), the African Development Fund (concessional financial assistance), and the Nigeria Trust Fund.

b. Approvals for financial assistance from ordinary capital resources (non-concessional financial assistance), Funds for Special Operation (FSO, concessional financial assistance), and other funds in administration by the IDB.

Financial assistance from the MDBs to emerging economies is controversial. Some argue that, instead of using MDB resources, these countries should rely on their own resources, particularly countries like China which has substantial foreign reserves holdings and can easily get loans from private capital markets to fund development projects. MDB assistance, it is argued, would be better suited to focusing on the needs of the world's poorest countries, which do not have the resources to fund development projects and cannot borrow these resources from international capital markets.

Others argue that MDB financial assistance provided to large, emerging economies is important, because these countries have substantial numbers of people living in poverty and MDBs provide financial assistance for projects for which the government might be reluctant to borrow. Additionally, MDB assistance helps address environmental issues, promotes better governance, and provides important technical assistance to which emerging economies might not otherwise have access. Finally, supporters argue that because MDB assistance to emerging economies takes the form of loans with market-based interest rates, rather than concessional loans or grants, this assistance is relatively inexpensive to provide.

Table 2 also shows the shows the top recipients of concessional financial assistance. Vietnam and Balgladesh were top recipients of financial assistance from IDA, the World Bank's concessional lending window, in FY2013. For the AsDF, the top recipients of financial assistance in 2012 were Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Afghanistan.

Funding: Donor Commitments and Contributions

MDBs are able to extend financial assistance to developing countries due to the financial commitments of their more prosperous member countries. This support takes several forms, depending on the type of assistance provided. The MDBs use money contributed or "subscribed" by their member countries to support their assistance programs. They fund their operating costs from money earned on non-concessional loans to borrower countries. Some of the MDBs transfer a portion of their surplus net income annually to help fund their concessional aid programs.

Non-Concessional Lending Windows

To offer non-concessional loans, the MDBs borrow money from international capital markets and then re-lend the money to developing countries. MDBs are able to borrow from international capital markets because they are backed by the guarantees of their member governments. This backing is provided through the ownership shares that countries subscribe as a consequence of their membership in each bank. |8| Only a small portion (typically less than 5-10%) of the value of these capital shares is actually paid to the MDB ("paid-in capital"). The bulk of these shares are a guarantee that the donor stands ready to provide to the bank if needed. This is called "callable capital," because the money is not actually transferred from the donor to the MDB unless the bank needs to call on its members' callable subscriptions. Banks may call upon their members' callable subscriptions only if their resources are exhausted and they still need funds to repay bondholders. To date, no MDB has ever had to draw on its callable capital. In recent decades, the MDBs have not used their paid-in capital to fund loans. Rather it has been put in financial reserves to strengthen the institutions' financial base.

Due to the financial backing of their member country governments, the MDBs are able to borrow money in world capital markets at the lowest available market rates, generally the same rates at which developed country governments borrow funds inside their own borders. The banks are able to relend this money to their borrowers at much lower interest rates than the borrowers would generally have to pay for commercial loans, if, indeed, such loans were available to them. As such, the MDBs' non-concessional lending windows are self-financing and even generate net income.

Periodically, when donors agree that future demand for loans from an MDB is likely to expand, they increase their capital subscriptions to an MDB's non-concessional lending window in order to allow the MDB to increase its level of lending. This usually occurs because the economy of the world or the region has grown in size and the needs of their borrowing countries have grown accordingly, or to respond to a financial crisis. An across the board increase in all members' shares is called a "general capital increase" (GCI). This is in contrast to a "selective capital increase" (SCI), which is typically small and used to alter the voting shares of member countries. The voting power of member countries in the MDB is determined largely by the amount of capital contributed and through selective capital increases; some countries subscribe a larger share of the new capital stock than others to increase their voting power in the institutions. GCIs happen infrequently. Quite unusually, all the MDBs are in the process of increasing the size of their non-concessional windows. Simultaneous for capital increases for all the MDBs has not occurred since the mid-1970s.

Table 3 summarizes current U.S. capital subscriptions to the MDB non-concessional lending windows. Currently, the largest U.S. share of subscribed MDB capital is with the IDB at nearly 30% while its smallest share among the MDBs is with the AsDB at just above 6%.

Table 3. MDB Non-Concessional Lending Windows: U.S. Financial Commitments

MDB U.S. Paid-in Capital

Billion $U.S. Callable Capital

Billion $Total U.S. Commitment

Billion $U.S. Share

%World Bank. FY2013 IBRD 2.23 33.58 35.81 16.05 IFC 0.57 -- 0.57 23.69 Regional Development Banks, 2012 AfDB 0.26 6.17 6.43 6.63 AsDB 1.27 24.17 25.45 15.60 EBRD 0.83 3.13 3.96 10.14 IDB 1.39 32.66 34.05 29.13 Source: MDB Annual Reports.

Notes: Values may not add due to rounding.Table 4 lists the top donors to the MDBs's non-concessional facilities. The United States has the largest financial commitments to the non-concessional lending windows to the IBRD, the IFC, the EBRD, and IDB. The United States is also essentially tied with Japan for the largest financial commitment to the AsDB. The United States is also a substantial donor to the AfDB.

Other top donor states include Western European countries, Japan, and Canada. Additionally, several regional members have large financial stakes in the regional banks. For example, among the regional members, China and India are large contributors to the AsDB; Nigeria, Egypt, and South Africa are large contributors to the AfDB; Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela are large contributors to the IDB; and Russia is a large contributor to the EBRD.

Table 4. MDB Non-Concessional Lending Windows: Top Donors

(Financial commitment, including callable and paid-in capital, as a % of total financial commitments)

World Bank, FY2013 IBRD % IFC % United States 16.05 United States 23.69 Japan 8.94 Japan 5.87 China 5.76 Germany 5.36 Germany 4.73 France 5.04 France 4.22 UK 5.04 United Kingdom 4.22 Canada 3.38 Canada 3.15 India 3.38 India 3.07 Italy 3.38 Italy 2.54 Russia 3.00 Russia 2.48 Netherlands 2.34 Saudi Arabia 2.48 Regional Development Banks, 2012 AfDB % AsDB % EBRD % IDB % Nigeria 9.34 Japan 15.61 United States 10.14 United States 29.13 United States 6.63 United States 15.60 France 8.64 Argentina 10.58 Japan 5.52 China 6.44 Germany 8.64 Brazil 10.58 Egypt 5.40 India 6.33 Italy 8.64 Canada 6.92 South Africa 4.84 Australia 5.79 Japan 8.64 Mexico 6.80 Algeria 4.23 Indonesia 5.44 United Kingdom 8.64 Venezuela 4.98 Germany 4.13 Canada 5.23 Russia 4.06 Japan 4.85 Libya 4.06 Korea 5.04 Canada 3.45 Chile 2.90 Canada 3.83 Germany 4.33 Spain 3.45 Colombia 2.90 France 3.78 Malaysia 2.72 European Investment Bank 3.04 France 1.84 European Union 3.04 Germany 1.84 Italy 1.84 Spain 1.84 Source: MDB Annual Reports.

Concessional lending windows do not issue bonds; their funds are contributed directly from the financial contributions of their member countries. Most of the money comes from the more prosperous countries, while the contributions from borrowing countries are generally more symbolic than substantive. The MDBs have also transferred some of the net income from their non-concessional windows to their concessional lending window in order to help fund concessional loans and grants.

As the MDB extends concessional loans and grants to low-income countries, the window's resources become depleted. The donor countries meet together periodically to replenish those resources. Thus, these increases in resources are called replenishments, and most occur on a planned schedule ranging from three to five years. If these facilities are not replenished on time, they will run out of lendable resources and have to substantially reduce their levels of aid to poor countries.

Table 5 summarizes cumulative U.S. contributions to the MDB concessional lending windows. The U.S. share of total contributions is highest to the IDB's concessional lending window and lowest to the AsDB's concessional lending window.

Table 5. MDB Concessional Lending Windows: Cumulative U.S. Contributions

MDB U.S. Contribution

Billion $U.S. Share

%World Bank, FY2013 IDA 46.54 20.75 Regional Development Banks, 2012 AfDF 3.53 10.91 AsDF 3.78 10.25 EBRD — — IDB: FSO 5.07 49.58 Source: MDB Annual Reports.

Notes: EBRD does not have a concessional lending window. Data may be pledged or actual paid-in commitments, depending on the institution.Table 6 shows the top donor countries to the MDB concessional facilities. The United States has made the highest cumulative contributions to IDA and the IDB's FSO, and the second highest cumulative contributions to the AfDF and the AsDF, after Japan. Other top donor states include the more prosperous member countries: Japan, Canada, and those in Western Europe. Within the FSO, regional members including Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, and Venezuela have also made substantial contributions.

Table 6. MDB Concessional Lending Windows: Top Donors

(Cumulative contributions)

World Bank, FY2013 Regional Development Banks, 2012 IDA % AfDF % AsDF % IDB: FSO % United States 20.75 Japan 11.31 Japan 50.07 United States 49.58 Japan 18.23 United States 10.91 United States 10.25 Japan 6.09 United Kingdom 11.14 Germany 10.26 Germany 5.31 Brazil 5.60 Germany 10.73 France 10.22 Canada 4.91 Argentina 5.20 France 7.09 United Kingdom 8.60 Australia 4.53 Mexico 3.38 Canada 4.56 Canada 7.18 France 3.73 Canada 3.20 Italy 4.26 Italy 5.72 United Kingdom 3.11 Venezuela 3.08 Netherlands 3.66 Sweden 5.30 Italy 2.52 Germany 2.36 Sweden 3.33 Norway 4.38 Netherlands 2.28 France 2.27 Belgium 1.81 Netherlands 4.16 Switzerland 1.35 Italy 2.22 Source: MDB Annual Reports.

Note: EBRD does not have a concessional lending window. Data may be pledged or actual paid-in commitments, depending on the institution.Relation to Other International Institutions

The World Bank is a specialized agency of the United Nations. However, it is autonomous in its decision-making procedures and its sources of funds. It also has autonomous control over its administration and budget. The regional development banks are independent international agencies and are not affiliated with the United Nations system. All the MDBs must comply with directives (for example, economic sanctions) agreed to (by vote) by the U.N. Security Council. However, they are not subject to decisions by the U.N. General Assembly or other U.N. agencies.

Internal Organization and U.S. Representation

The MDBs have similar internal organizational structures. Run by their own management and staffed by international civil servants, each MDB is supervised by a Board of Governors and a Board of Executive Directors. The Board of Governors is the highest decision-making authority, and each member country has its own governor. Countries are usually represented by their Secretary of the Treasury, Minister of Finance, or Central Bank Governor. The United States is currently represented by Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew. The Board of Governors meets annually, though may act more frequently through mail-in votes on key decisions.

While the Boards of Governors in each of the Banks retain power over major policy decisions, such as amending the founding documents of the organization, they have delegated day-to-day authority over operational policy, lending, and other matters to their institutions' Board of Executive Directors. The Board of Executive Directors in each institution is smaller than the Board of Governors. There are 24 members on the World Bank's Board of Executive Directors, and fewer for some of the regional development banks. Each MDB Executive Board has its own schedule, but they generally meet at least weekly to consider MDB loan and policy proposals and oversee bank activities.

The current U.S. Executive Directors to the MDBs are listed in Table 7. Two U.S. Executive Director positions at the MDBs are currently vacant. When an Executive Director position is vacant, the rules governing the MDBs generally permit Alternate Executive Directors, if appointed, to fulfill the same roles and functions as an Executive Director would. When both the Executive Director and Alternate Director positions are vacant at a MDB, Treasury considers what interim steps are needed to ensure effective U.S. participation, taking into account personnel and legal constraints, as well as the bylaws of the particular institution.

Table 7. U.S. Executive Directors

MDB U.S. Executive Director World Bank Vacant AfDB Jones Walter Crawford AsDB Robert Orr EBRD Vacant IDB Gustavo Arnavata Source: MDB websites.

a. In September 2013, the Obama Administration announced it was nominating Mark Lopes to be the U.S. Executive Director at the IDB, pending Senate confirmation.Decisions are reached in the MDBs through voting. Each member country's voting share is weighted on the basis of its cumulative financial contributions and commitments to the organization. |9| Table 8 shows the current U.S. voting power in each institution. The voting power of the United States is large enough to veto major policy decisions at the World Bank and the IDB. However, the United States cannot unilaterally veto more day-to-day decisions, such as individual loans.

Table 8. U.S. Voting Power in the MDBs

MDB U.S. Voting Share (%) World Bank Group, FY2013 IBRD 15.19 IDA 10.71 IFC 22.41 Regional Banks, 2012 AfDB 6.59 AfDF 5.49 AsDB 12.78 IDB 30.03 EBRD 10.16 Source: MDB Annual Reports.

Debates about Effectiveness of the MDBs

The effectiveness of foreign aid, including the aid provided by MDBs, in spurring economic development and reform in developing countries, is contested. Many academic studies of foreign aid effectiveness typically examine the effects of total foreign aid provided to developing countries, including both bilateral aid and multilateral aid. With bilateral aid, most U.S. resources go directly to programs and projects in developing countries. With multilateral aid, multilateral organizations, like the MDBs, pool money from different donors and then provide money to fund programs and projects in developing countries. The results of these studies that examine the effectiveness of bilateral and multilateral aid are mixed, with conclusions ranging from (a) aid is ineffective at promoting economic growth |10| to (b) aid is effective at promoting economic growth |11| to (c) aid is effective at promoting growth in some countries under specific circumstances (such as when developing-country policies are strong). |12| The divergent results of these academic studies make it difficult to reach firm conclusions about the overall effectiveness of aid.

Beyond the debates about the overall effectiveness of foreign aid, there are also criticisms of the providers of foreign aid. Many of these criticisms are made broadly about multilateral aid organizations and government aid agencies, and are not targeted at the MDBs specifically. For example, it is argued that the national and international bureaucracies that dispense foreign aid focus on "getting money out the door" to developing countries, rather than on delivering services to developing countries; emphasize short-term outputs like reports and frameworks but do not engage in long-term activities like the evaluation of projects after they are completed; and put enormous administrative demands on developing-country governments. |13| Bilateral and multilateral foreign aid agencies have also been criticized for their lack of transparency about their operating costs and how they spend their aid money; the fragmentation of foreign aid across many small aid bureaucracies that are not well coordinated; and the proportion of foreign aid that goes to corrupt leaders or is spent ineffectively. |14| However, some analysts contend that among government and international foreign agencies, MDBs ranked among the best for adhering to foreign aid "best practices." |15| Many of these criticisms and proposals for change are discussed in a March 2010 report by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on the international financial institutions (IFIs). |16|

Proponents of foreign aid argue that, despite some flaws, such aid at its core serves vital economic and political functions. With 1.4 billion people in the developing world (one in four people in the developing world) living on less than $1.25 a day in 2005, |17| some argue that not providing assistance is simply not an option; they argue it is the "right" thing to do and part of "the world's shared commitments to human dignity and survival." |18| These proponents typically point to the use of foreign aid to provide basic necessities, such as food supplements, vaccines, nurses, and access to education, to the world's poorest countries. Additionally, proponents of foreign aid argue that, even if foreign aid has not been effective at raising overall levels of economic growth, foreign aid has been successful in dramatically improving health and education in developing countries over the past four decades. For example, it is argued that foreign aid contributed to rising life expectancy in developing countries from 48 years to 68 years over the past four decades, and lowering infant mortality from 131 out of every 1,000 babies born in developing countries to 36 out of every 1,000 babies. |19| It is also argued that providing foreign aid is an important component of U.S. national security policy and U.S. leadership in the world.

Bilateral vs. Multilateral Aid

There are also policy debates about the merits of giving aid bilaterally or multilaterally. |20| Bilateral aid gives donors more control over where the money goes and how the money is spent. For example, donor countries may have more flexibility to allocate funds to countries that are of geopolitical strategic importance, but not facing the greatest development needs, than might be possible by providing aid through a multilateral organization. By building a clear link between the donor country and the recipient country, bilateral aid may also garner more goodwill from the recipient country towards the donor than if the funds had been provided through a multilateral organization.

Providing aid through multilateral organizations offers different benefits for donor countries. Multilateral organizations pool the resources of several donors, allowing donors to share the cost of development projects (often called burden-sharing). Additionally, donor countries may find it politically sensitive to attach policy reforms to loans or to enforce these policy reforms. Multilateral organizations can usefully serve as a scapegoat for imposing and enforcing conditionality that may be politically sensitive to attach to bilateral loans. Finally, many believe that providing funds to multilateral organizations is important for enhancing and symbolizing U.S. leadership in the world economy.

The United States provides most of its foreign aid for promoting economic and social development bilaterally rather than multilaterally. Data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) reports that in 2011, 12% of U.S. foreign aid disbursed to developing countries with the purpose of promoting economic and social development was provided through multilateral institutions, while 88% was provided bilaterally. |21| Figure 3 shows that the level of multilateral aid disbursed by the United States has remained fairly constant since 2000, although U.S. bilateral aid for development has increased.

OECD-DAC data allows comparison of the United States with other developed countries. Generally, other developed countries typically disburse a higher proportion of their development assistance through multilateral institutions than the United States does. For example, 34% of Germany's, 20% of Japan's, and 38% of the United Kingdom's foreign aid for economic and social development in 2011 was disbursed to multilateral organizations. |22|

Figure 3. U.S. Bilateral and Multilateral Official Development Assistance, 2000-Present

(Billion $)

Source: OECD.

Notes: DAC reports data on gross disbursements at current prices of official development assistance (ODA). ODA is defined as flows to developing countries and multilateral institutions which are administered with the promotion of economic development and is concessional in character and conveys a grant element of at least 25%. DAC data does not include, for instance, other official flows including military assistance. DAC data also focuses on the disbursements of ODA, and would not include, for example, the callable capital committed by the United States to the MDBs, because this money has never actually been disbursed from the United States to the MDBs. Also, multilateral organizations not only include the MDBs but also U.N. agencies.An alternative data source for U.S. multilateral and bilateral economic assistance to developing countries is U.S. Overseas Loans and Grants: Obligations and Loan Authorization, published by U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). |23| According to this publication, commonly referred to as the "Greenbook," 8.4% of U.S. economic assistance in 2011 was provided to multilateral organizations. The data is drawn from the same source as the data provided by the United States to the OECD-DAC, but the totals are different due to differences between the definitions of economic assistance used by OECD-DAC and the Greenbook.

Congress plays an important role in authorizing and appropriating U.S. contributions to the MDBs and exercising oversight of U.S. participation in these institutions. The MDBs provide commercial opportunities for U.S. firms, and one area of potential oversight is potential changes to the procurement policies at the MDBs. For more details on U.S. policy-making at the MDBs, see CRS Report R41537, Multilateral Development Banks: How the United States Makes and Implements Policy, by Rebecca M. Nelson and Martin A. Weiss.

Authorizing and Appropriating U.S. Contributions to the MDBs

Authorizing and appropriations legislation is required for U.S. contributions to the MDBs. The Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and the House Committee on Financial Services are responsible for managing MDB authorization legislation. During the past several decades, authorization legislation for the MDBs has not passed as freestanding legislation. Instead, it has been included through other legislative vehicles, such as the annual foreign operations appropriations act, a larger omnibus appropriations act, or a budget reconciliation bill. The Foreign Operations Subcommittees of the House and Senate Committees on Appropriations manage the relevant appropriations legislation. MDB appropriations are included in the annual foreign operations appropriations act or a larger omnibus appropriations act.

In recent years, the Administration's budget request for the MDBs has included three major components: funds to replenish the concessional lending windows, funds to increase the size of the non-concessional lending windows (the "general capital increases"), and funds for more targeted funds administered by the MDBs, particularly those focused on climate change and food security. |24| Replenishments of the MDB concessional windows happen regularly, while capital increases for the MDB non-concessional windows occur much more infrequently. Quite unusually, all the MDBs are in the process of increasing their non-concessional windows, primarily to address the increase in demand for loans that resulted from the financial crisis, prepare for future crises, and, in the case of the IDB, recover from financial losses resulting from the financial crisis. Simultaneous capital increases for all the MDBs has not happened since the 1970s. For more information on the general capital increases, see CRS Report R41672, Multilateral Development Banks: General Capital Increases, by Martin A. Weiss. Data on U.S. contributions (including requests and appropriated funds) to the MDBs can be found in CRS Report RS20792, Multilateral Development Banks: U.S. Contributions FY2000-FY2014, by Rebecca M. Nelson.

Congressional Oversight of U.S. Participation in the MDBs

As international organizations, the MDBs are generally exempt from U.S. law. The President has delegated the authority to manage and instruct U.S. participation in the MDBs to the Secretary of the Treasury. Within the Treasury Department, the Office of International Affairs has the lead role in managing day-to-day U.S. participation in the MDBs. The President appoints the U.S. Executive Directors, and their alternates, with the advice and consent of the Senate. Thus, the Senate can exercise oversight through the confirmation process.

Over the years, Congress has played a major role in U.S. policy towards the MDBs. In addition to congressional hearings on the MDBs, Congress has enacted a substantial number of legislative mandates that oversee and regulate U.S. participation in the MDBs. These mandates generally fall into one of four major types. More than one type of mandate may be used on a given issue area.

First, some legislative mandates direct how the U.S. representatives at the MDBs can vote on various policies. Examples include mandates that require the U.S. Executive Directors to oppose: (a) financial assistance to specific countries, such as Burma, until sufficient progress is made on human rights and implementing a democratic government; |25| (b) financial assistance to broad categories of countries, such as major producers of illicit drugs; |26| and (c) financial assistance for specific projects, such as the production of palm oil, sugar, or citrus crops for export if the financial assistance would cause injury to United States producers. |27| Some legislative mandates require the U.S. Executive Directors to support, rather than oppose, financial assistance. For example, a current mandate allows the Treasury Secretary to instruct the U.S. Executive Directors to vote in favor of financial assistance to countries that have contributed to U.S. efforts to deter and prevent international terrorism. |28|

Second, legislative mandates direct the U.S. representatives at the MDBs to advocate for policies within the MDBs. One example is a mandate that instructs the U.S. Executive Director to urge the IBRD to support an increase in loans that support population, health, and nutrition programs. |29| Another example is a mandate that requires the U.S. Executive Directors to take all possible steps to communicate potential procurement opportunities for U.S. firms to the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Commerce, and the business community. |30| Mandates that call for the U.S. Executive Director to both vote and advocate for a particular policy are often called "voice and vote" mandates.

Third, Congress has also passed legislation requiring the Treasury Secretary to submit reports on various MDB issues (reporting requirements). Some legislative mandates call for one-off reports; other mandates call for reports on a regular basis, typically annually. For example, current legislation requires the Treasury Secretary to submit an annual report to the appropriate congressional committees on the actions taken by countries that have borrowed from the MDBs to strengthen governance and reduce the opportunity for bribery and corruption. |31|

Fourth, Congress has also attempted to influence policies at the MDBs through "power of the purse," that is, withholding funding from the MDBs or attaching stipulations on the MDBs's use of funds. For example, the FY2010 Consolidated Appropriations Act stipulates that 10% of the funds appropriated to the AsDF will be withheld until the Treasury Secretary can verify that the AsDB has taken steps to implement specific reforms aimed at combating corruption. |32|

U.S. Commercial Interest in the MDBs

Billions of dollars of contracts are awarded to private firms each year in order to acquire the goods and services necessary to implement projects financed by the MDBs. MDB contracts are awarded through international competitive bidding processes, although most MDBs allow the borrowing country to give some preference to domestic firms in awarding contracts for MDB-financed projects in order to help spur development.

U.S. commercial interest in the MDBs has been and may continue to be a subject of Congressional attention, particularly if the banks expand their lending capacity for infrastructure projects through the GCIs. One area of focus may be the Foreign Commercial Services (FCS) representatives to the MDBs, who are responsible for protecting and promoting American commercial interests at the MDBs. |33| Some in the business community are concerned about the impacts of possible budget cuts to the U.S. FCS, particularly if other countries are taking a stronger role in helping their businesses bid on projects financed by the MDBs.

There may also be interest in discussions about policy changes for procurement standards at the World Bank, who awards the largest number and highest volume of contracts each year. In January 2011, the World Bank Executive Board approved a pilot program for a new lending instrument, "Program for Results," or P4R. |34| This new lending instrument links the disbursement of funds directly to the delivery of defined results. Proponents argue that P4R will help developing countries improve the design and implementation of their development programs, and help strengthen their institutions and build capacity. Opponents argue that relying on country's own systems could undermine adequate social and environmental safeguards, while also undermining transparency objectives and accountability commitments. |35|

[Source: By Rebecca M. Nelson, Congressional Research Service, 08Nov13. Rebecca M. Nelson is an Analyst in International Trade and Finance. Amber Wilhelm, Graphics Specialist, prepared the graphs.]

Notes:

1. There are also several sub-regional development banks, such as the Caribbean Development Bank and the Andean Development Corporation. However, the United States is not a member of these sub-regional development institutions, and they are not discussed in this report. This report also does not discuss the North American Development Bank (NADBank), a binational financial institution capitalized and governed by the United States and Mexico. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), whose mandate is to ensure international financial stability, is not an MDB. For more on the IMF, see CRS Report R42019, International Monetary Fund: Background and Issues for Congress, by Martin A. Weiss. [Back]

2. These carry repayment terms that are lower than those normally required for commercial loans, but they are not subsidized. See the discussion of financing below. [Back]

3. Countries that are eligible for concessional and non-concessional assistance are often referred to as "blend" countries. [Back]

4. In addition to the IBRD, IDA, and the IFC, the World Bank Group also includes the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). The term "World Bank" typically refers to IBRD and IDA specifically. MIGA and ICSID are not covered in this report, even though they arguably play an important role in fostering economic development, because they do not make loans and grants to developing countries. MIGA provides political risk insurance to foreign investors, in order to promote foreign direct investment (FDI) into developing countries. ICSID provides facilities for conciliation and arbitration of disputes between governments and private foreign investors. [Back]

5. Sarah Babb, Behind the Development Banks: Washington Politics, World Poverty, and the Wealth of Nations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009). [Back]

6. The World Bank reports operations data for the fiscal year (July - June), while the regional MDBs report data on a calendar year. Throughout this report, World Bank data is for fiscal years and regional MDB data is for calendar years. [Back]

7. Including IBRD, IFC, and IDA. [Back]

8. In most cases, the banks do not use the capital subscribed by their developing country members as backing for the bonds and notes they sell to fund their market-rate loans to developing countries, but instead just use the capital subscribed by their developed country members. [Back]

9. This is not necessarily the case with the MDBs' concessional windows, though. In order to insure that borrower countries have at least some say in these organizations, the contributions of donor countries in some recent replenishments have not given the donor countries additional votes. In all cases, though, the donor countries together have a comfortable majority of the total vote. [Back]

10. E.g., see William Easterly, "Can Foreign Aid Buy Growth?," Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 17, no. 3 (Summer 2003), pp. 23-48. [Back]

11. E.g., see Carl-Johan Dalgaard and Henrik Hansen, "On Aid, Growth, and Good Policies," Journal of Development Studies, vol. 37, no. 6 (August 2001), pp. 17-41. [Back]

12. E.g., see Craig Burnside and David Dollar, "Aid, Policies, and Growth," American Economic Review, vol. 90, no. 4 (September 2000), pp. 847-868. [Back]

13. William Easterly, "The Cartel of Good Intentions," Foreign Policy, vol. 131 (July-August 2002), pp. 40-49. [Back]

14. William Easterly and Tobias Pfutze, "Where Does the Money Go? Best and Worst Practices in Foreign Aid," Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 22, no. 2 (Spring 2008). For more on foreign aid reform, also see CRS Report R40102, Foreign Aid Reform: Studies and Recommendations, by Susan B. Epstein and Matthew C. Weed and CRS Report R40756, Foreign Aid Reform: Agency Coordination, by Marian L. Lawson and Susan B. Epstein. [Back]

16. U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, The International Financial Institutions: A Call for Change, 111th Cong., 2nd sess., March 10, 2010, http://foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/55285.pdf. [Back]

17. World Bank, New Data Show 1.4 Billion Live On Less Than US$1.25 A Day, But Progress Against Poverty Remains Strong, August 26, 2008, http://go.worldbank.org/F9ZJUH97T0. [Back]

18. Jeffrey Sachs, The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time (Penguin Books, 2006), p. xvi. [Back]

19. William Easterly, The White Man's Burden (New York: Penguin Press, 2006), pp. 176-177. [Back]

20. For more on the choice between bilateral and multilateral aid, see, for example: Helen Milner and Dustin Tingley, "The Choice for Multilateralism: Foreign Aid and American Foreign Policy," Working Paper, February 10, 2010 and Helen Milner, "Why Multilateralism? Foreign Aid and Domestic Principal-Agent Problems," in Delegation and Agency in International Organizations, eds. Darren Hawkins et al. (New York City: Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp. 107-139. [Back]

21. See the note in Figure 3 for explanation of OECD aid data. It does not, for example, include military assistance provided by the United States or the callable capital committed by the United States to the MDBs. [Back]

22. Gross disbursements at current prices. [Back]

23. Available at http://catalog.data.gov/dataset/us-overseas-loans-and-grants-greenbook. [Back]

24. For information about the FY2013 budget request, see U.S. Department of Treasury, International Programs: Justification for Appropriations, FY2013 Budget Request, http://www.treasury.gov/about/budget-performance/Documents/FY2013_CPD_FINAL_508.pdf. [Back]

25. Section 570(a)(2) of the Omnibus Consolidated Appropriations Act, 1997 (P.L. 104-208). Also on human rights more broadly, see 22 USCS §262d. [Back]

26. 22 USC §2291j(a)(2). [Back]

28. 22 USC §262p-4r(a). [Back]

31. 22 USC §262r-6(b)(2). [Back]

32. Section 7086 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2010 (P.L. 111-117). [Back]

33. For more information, see http://www.export.gov/advocacy/eg_main_022753.asp. [Back]

34. World Bank, "Program-for-Results Financing (PforR)," Accessed April 16, 2012, http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/PROJECTS/EXTRESLENDING/0,,contentMDK:22748955~pagePK:7321740~piPK:7514729~theSitePK:7514726,00.html. [Back]

35. Bank Information Center, "P4R Update: World Bank Approves Program for Results Policy," February 29, 2012, http://www.bicusa.org/en/Article.12602.aspx. [Back]

| This document has been published on 12Dec13 by the Equipo Nizkor and Derechos Human Rights. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. |