| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

Oct15

Gain or more pain in Spain?

- Spain is the eurozone's latest poster child for austerity and structural reforms. The country's economy is growing robustly on the back of strong employment growth, recovering real wages and a pick-up in business investment. Indeed, Spain is on course to be the fastest expanding big economy in the EU this year.

- Spain's return to growth is good news, but there is little evidence that it is the result of austerity and reforms. Moreover, the economy's outlook is cloudier than the dominant narrative would suggest and the challenges facing the country remain formidable.

- Inflation will be too low to erode the real value of the country's daunting debt burden. Unemployment will remain high for many years and continue to bear down on prices. And the ECB will shy away from the aggressive monetary easing needed to raise Spanish inflation.

- Real borrowing costs are highest in weak eurozone countries such as Spain (where inflation is lowest), and lowest in the strongest (where inflation is highest), leading capital and skilled labour to flow to the eurozone's stronger economies. The Spanish government cannot boost government spending to counter this effect and the eurozone lacks fiscal mechanisms to compensate weaker member-states for it.

- Spain needs stronger productivity growth if living standards are to converge with those in wealthier EU countries. But there is little sign that investment is switching from lower to higher value-added activities. Most of the jobs created over the last couple of years have comprised poorly-paid service sector employment, especially in tourism.

- Spain's relatively strong export performance since the depth of the crisis has been powered by sectors such as fuel and food rather than a move into higher value-added sectors. Recovering domestic demand will lead imports to rise more rapidly than exports, causing a renewed current account deficit and worsening of Spain's already very weak net external asset position.

- Construction activity has bottomed out, but is set to stagnate at low levels of activity given Spain's poor demographics and the country's overhang of empty homes, some of which are being demolished but many of which will continue to weigh on the market.

- One of the lowest birth rates in the world and net emigration means that Spain's working age population is set to shrink rapidly. This might not sound like a problem for a country with mass unemployment, but countries with shrinking workforces tend to suffer weak economic growth, which makes public and private debt harder to pay back.

- Spain is likely to enter the next downturn having barely recovered from the previous recession, with high levels of public and private sector indebtedness, and unemployment well above pre-crisis levels. Crucially, it will have few policy tools available to combat a renewed weakening of domestic demand, which increases the likelihood that the next recession will be a deep one.

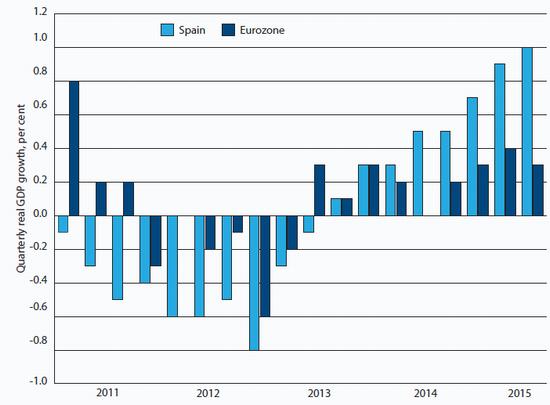

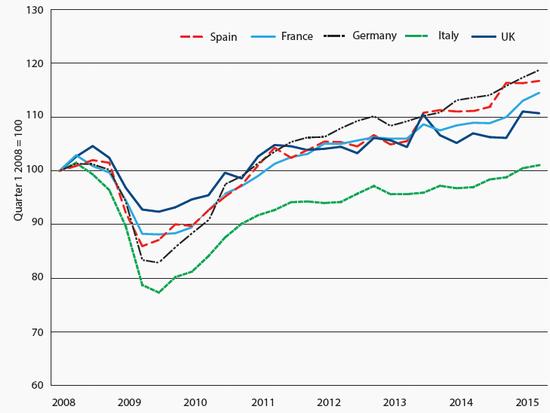

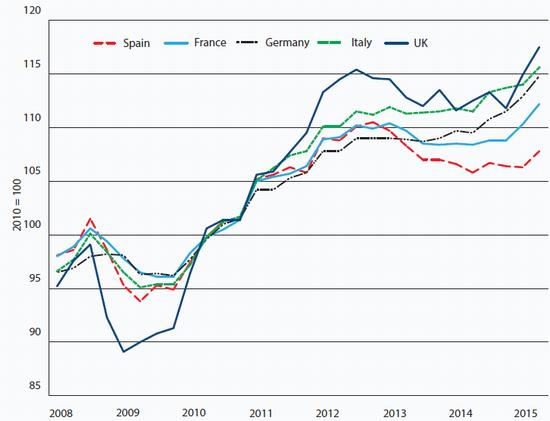

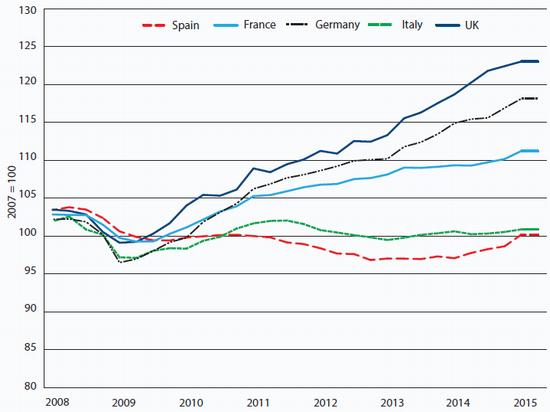

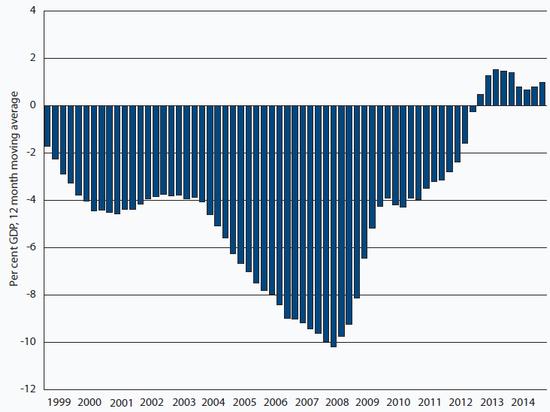

Spain's economy has now expanded for eight consecutive quarters, steadily gaining momentum and easily outperforming the rest of the currency union (see Chart 1). Economic growth topped 3 per cent in the year to the middle of 2015. Employment grew by a similar margin, which together with rising real wages, underpinned robust consumption. Investment in machinery and equipment also picked up strongly, as business confidence gradually returned. These are good numbers, but they are rather misleading. And there is no evidence that they are the result of austerity and not much evidence that they are the product of structural reforms.

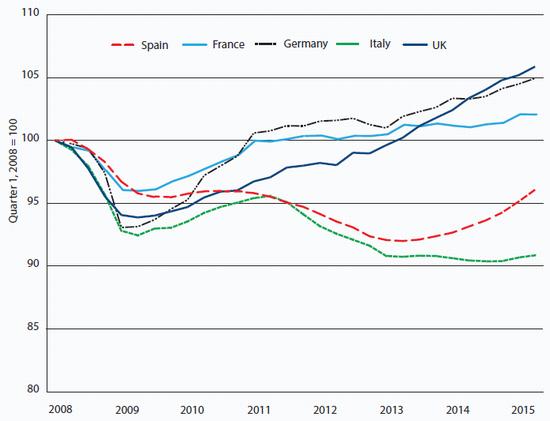

Spain's economy is growing relatively rapidly, but it is doing so from low base. The level of economic activity remains depressed compared to pre-crisis levels: too many commentators are confusing the level of activity with the rate of growth in that activity. Even assuming that the economy expands by 3 per cent in 2015 and 2.5 per cent in 2016, it will not recover its pre-crisis size before 2017 (see Chart 2). By contrast, had the Spanish economy grown by 2 per cent annually since 2008 (that is, at half its rate of expansion between 1999 and 2007), it would be over a fifth larger than it is now.

Chart 1: Economic growth in Spain outpacing the eurozone

Source: Haver Analytics

Chart 2: Spanish real GDP still well below pre-crisis level

Source: Haver Analytics

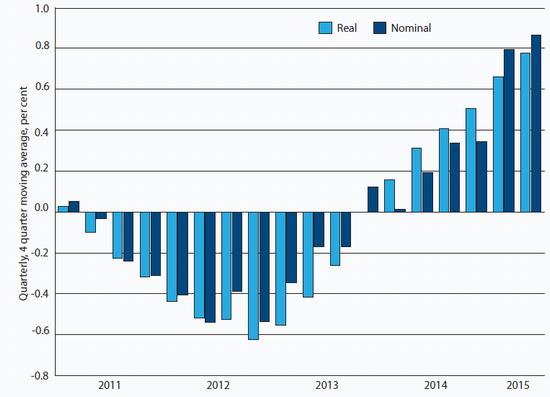

Second, there are significant difficulties in measuring economic growth when inflation is weak or prices are falling. In the four years to June 2015, real GDP growth actually exceeded growth in nominal GDP (see Chart 3). This was only possible because the prices of many goods and services fell, boosting real spending power. However, if the Spanish authorities have overestimated the weakness of prices (and revisions to the so-called GDP deflator are frequent and often large), real growth may well have been smaller than the current data suggest.

Chart 3: Growth in Spain's real and nominal GDP

Source: Haver Analytics

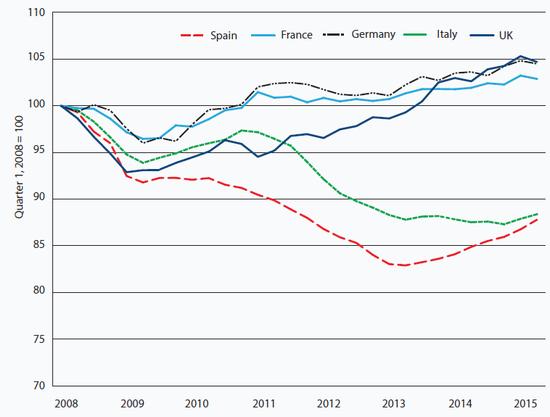

Chart 4: Spanish domestic demand still depressed

(Aggregate spending that includes imports but not exports; constant 2010 prices)

Source: Haver Analytics

Third, the data for real GDP give a misleading impression of what has happened to activity in the domestic economy. Domestic demand (that is, consumption and investment) is still 12 per cent lower than the pre-crisis peak, and is unlikely to recover that lost ground until 2020 at the earliest (see Chart 4). The gulf between GDP and domestic demand reflects the collapse of imports, which were 15 per cent lower in the second quarter of 2015 relative to the final one of 2007; exports were up 18 per cent over this period.

While the rise in exports is good news, the scale of the fall in imports is not, reflecting declining living standards, mass unemployment and (notwithstanding a slight recovery) depressed investment (see Chart 5). Moreover, Spain's relatively strong export performance has not been enough to bring about a recovery in industrial production, which was lower in mid-2015 than it was at the depth of the crisis in 2009 (see Chart 6).

Chart 5: Spain's investment recovery has barely started

(Spending on fixed assets, such as factories, machinery, equipment, buildings; constant 2010 prices)

Source: Haver Analytics

Chart 6: Spanish industrial production: A long way to go

(Industrial production excluding construction)

Source: Haver Analytics

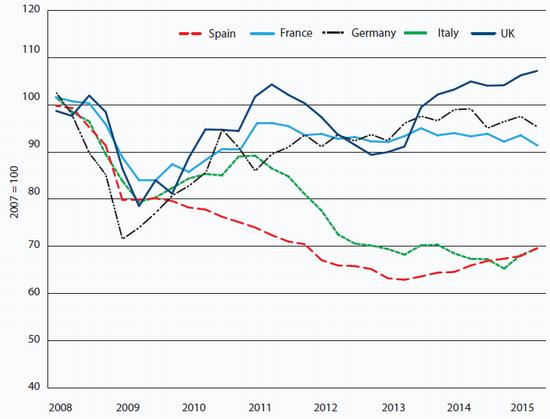

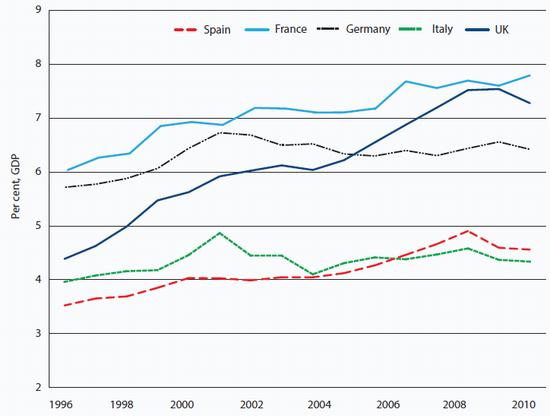

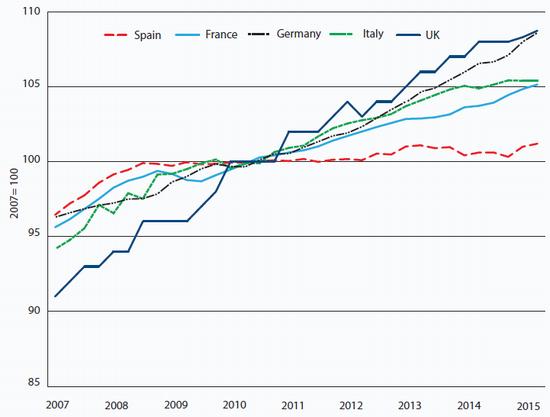

Neither is the employment miracle quite what it is cracked up to be. Employment has certainly risen strongly since the beginning of 2014, but from an extremely low base: it is still down 14 per cent compared with the pre-crisis period. Employment fell much more strongly in Spain during the crisis than in the other EU economies, including those that experienced comparable collapses in demand, such as Italy (see Chart 7). Spanish firms opted to lay off labour rather than hold onto it in the hope that things would soon get better. Moreover, the 1.1 million fall in the number of unemployed over the last two years partly reflects a shrinking labour force, down 300,000 over this period. Moreover, full time jobs are still down almost 18 percent (3.2 million); part-time ones have increased by around 16 per cent (400,000).

Chart 7: Spain's employment 'miracle' in perspective

(Full and part-time jobs, 15 year olds and over)

Source: Haver Analytics

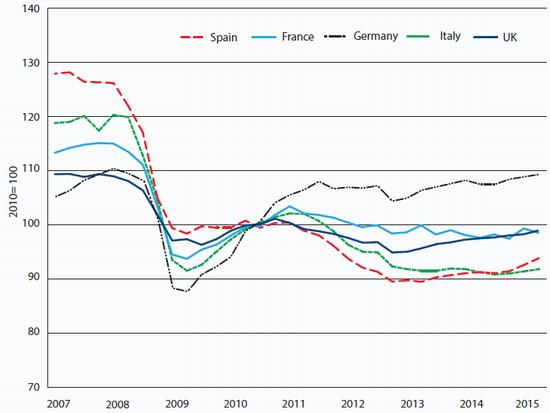

Chart 8: Falling prices boost real wages

(Industry, construction and services)

Source: Haver Analytics

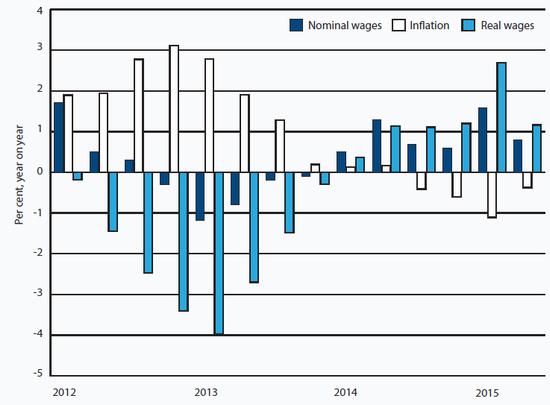

The return to real wage growth, which has provided the principal boost to economic activity over the last year, almost certainly reflects temporary factors (see Charts 8 and 9). While growth in nominal wages has picked up since the beginning of 2014, the return to positive growth in real wages also reflects the decline in inflation, which has turned negative. It is likely that real wage growth will prove short-lived: nominal wage settlements will probably fall as wage negotiators adjust to much lower inflation. Indeed, there are indications that this is already happening, with the rate of growth in nominal wages slowing sharply in the second quarter of 2015.

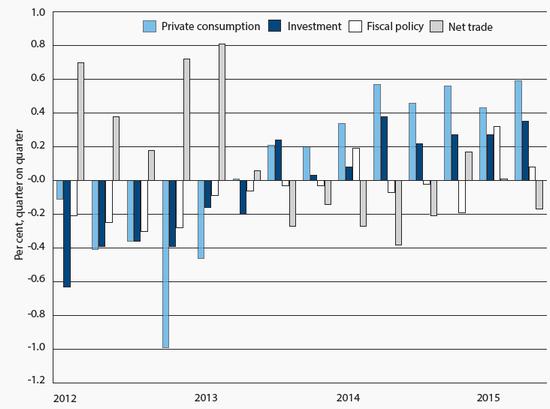

Chart 9: Consumption drives Spain's recovery

(Quarterly growth, real GDP)

Source: Haver Analytics

Chart 10: Spanish exports keep pace with Germany's

(Exports of goods and services; constant 2010 prices)

Source: Haver Analytics

Spain's return to economic growth is certainly not the result of austerity. There is little doubt that there were formidable cutbacks in Spain earlier in the crisis, but the pace of austerity had eased off by the second half of 2013 and fiscal policy has been mildly expansionary since the beginning of 2014. Nor was it possible for Spain to ease off the austerity because its fiscal deficit had fallen to under 3 per cent of GDP: Spain's fiscal deficit was 6.8 per cent of GDP in 2013 and 5.8 per cent in 2014, the biggest in the EU. The recovery in business investment certainly cannot be attributed to fiscal consolidation opening the way for a recovery in business confidence, as per the austerian narrative. Rather, the easing of austerity appears to have paved the way for a return to growth.

Spain's export performance since the trough of the downturn has been relatively good, with growth in exports of goods and services keeping pace with Germany's (see Chart 10). There are a number of possible explanations for this. One is that the fall in domestic demand forced Spanish firms to seek sales abroad. However, other countries such as Italy experienced a comparable fall in domestic demand without a comparable rise in exports. Another explanation is that Spain exports a lot of intermediate goods to German multinationals, which have performed well on rising exports to China and other non-European markets. But there is little evidence that Spain is more tied into these supply-chains than is Italy.

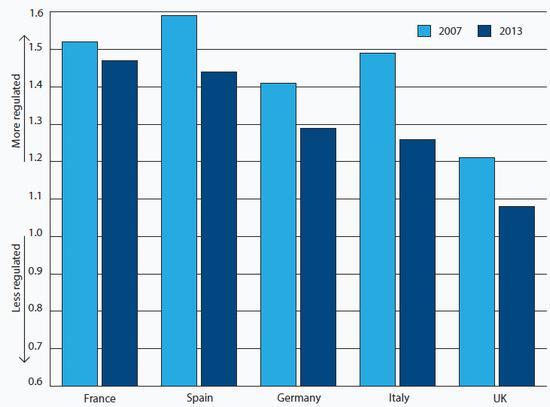

Another oft-cited reason for Spain's relatively strong export performance is that Spanish firms are reaping the rewards of structural reforms, which have boosted the competitiveness of the Spanish economy and hence its exports. The OECD compiles indices of the levels of market regulation in developed countries. These indices for product and labour market regulation are not perfect, but they are rigorous and comparative. According to the OECD's index, Spain's markets for goods and services are freer than they were before the crisis, suggesting that structural reforms have been effective (see Chart 11). But Italy has made greater progress and from a more favourable starting point. Incidentally, the OECD calculates that Italy now has freer markets for good and services than Germany, the implicit benchmark for economic performance in the eurozone.

Chart 11:

Regulatory obstacle to entrepreneurship, trade and investment

Source: OECD

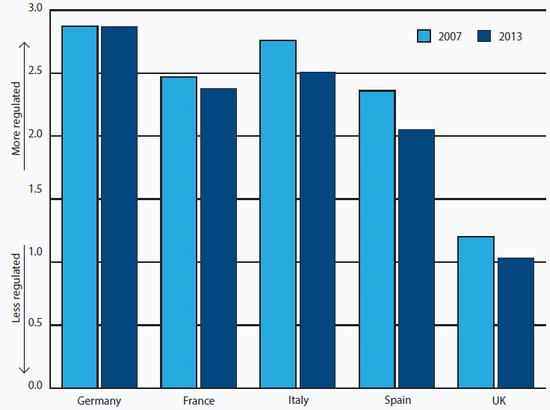

Chart 12: Strictness of employment legislation for permanent contracts

(Individual and collective dismissals)

Source: OECD

The OECD's labour market indices also confirm a modest deregulation of Spain's labour market (see Charts 12 and 13). But there is little empirical evidence linking deregulated labour markets with improved competitiveness and exports. For example, on some measures, Germany's labour market is more regulated than that of France, Italy or Spain. And the UK has easily the most competitive labour and product markets, but suffers from poor export performance. In short, there is little to suggest that structural reforms lie behind Spain's export record.

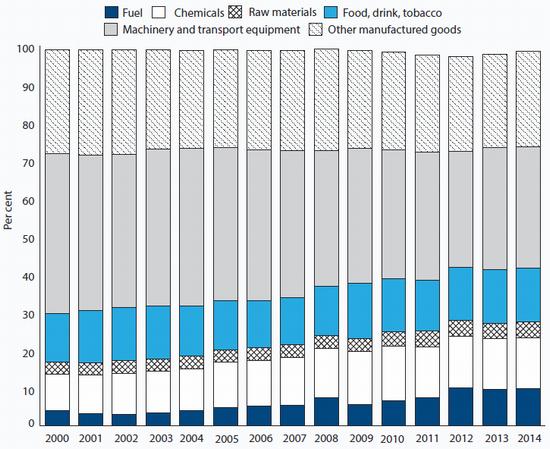

Were Spanish reforms boosting innovation and productivity, this would be showing up in a structural shift in favour of higher-valued goods in the composition of Spanish exports. Yet the proportion of exports comprising low value-added goods - fuels, food and raw materials - has risen rather than fallen (see Chart 14). Half the rise in goods exported between 2007 and 2014 was accounted for by fuels, food and raw materials. If chemicals (many of which are relatively low value-added) are included, this proportion rises to almost two-thirds.

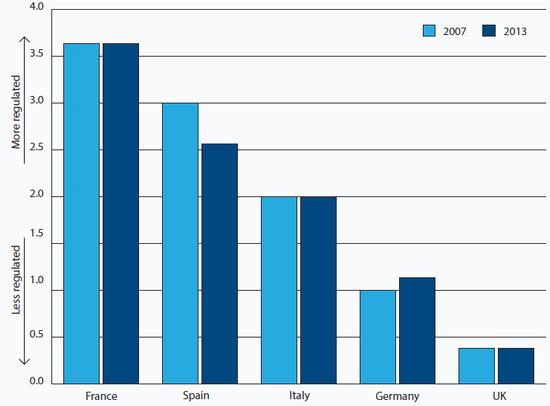

Chart 13: Strictness of employment protection for temporary contracts

Source: OECD

Chart 14: Composition of Spanish exports

Source: Haver Analytics

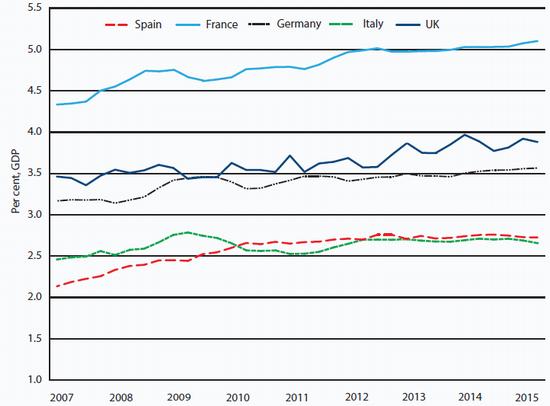

A move up the value-chain would require Spanish firms to step up their investment in intangibles such as research and development (R&D), training and advertising. The latest available data for investment in intangibles is from 2010 and show that Spain was one of the poorest performers in the EU-15 (see Chart 15). There is little to suggest that Spain's performance has improved much since. For example, spending on intellectual property has risen in Spain but not by enough to suggest a big structural change in favour of higher value-added activities (see Chart 16).

Chart 15: Investment in 'intangibles'

(R&D, design, new financial products, advertising, market research, training and organisational capital)

Source: IntanInvest (The Conference Board; Luiss Lab of European Economies)

Chart 16: Investment in intellectual property

Source: Haver Analytics

A more compelling reason for Spain's relatively strong export performance since 2008 can be found in the export price data (see Chart 17): Spanish export prices have risen much less than those of the other big European countries. Big falls in Spanish unit wage costs have reduced the prices of the country's goods and services relative to other countries in the region, enabling Spain to boost market share. Without an independent currency, this is arguably what a country in a currency union needs to do, if it is suffering from a loss of competitiveness. But it not clear that this applies to Spain: Spanish export prices did not rise too rapidly prior to the crisis and Spain's export performance was relatively good during this period.

Chart 17: Spain gains market share by holding down costs

(Export prices)

Source: Haver Analytics

Chart 18: Spanish nominal GDP no higher than in 2008

(GDP at current prices)

Source: Haver Analytics

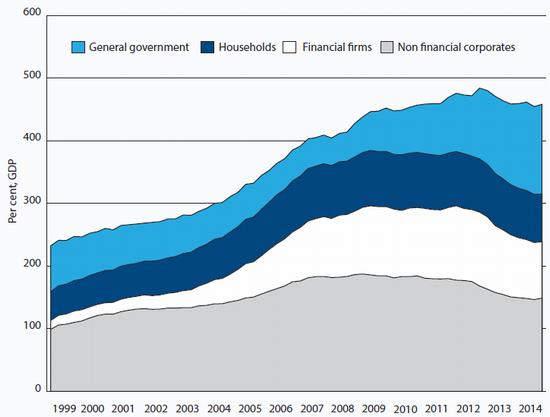

The flipside of Spain's weak export prices has been deflation, which poses a raft of problems for the country. Chart 18 shows the path of Spanish nominal GDP (real GDP plus inflation). The extreme weakness of Spanish nominal GDP - it is lower than it was seven ago - reflects the fall in real GDP, but also weak inflation (see Chart 19). As noted above, official estimates of Spain's GDP deflator may well yet be revised upwards, but there is no doubting the scale of deflationary pressure in the country. Nominal GDP growth matters, which is why most central banks implicitly target growth in it of 4-5 per cent per annum. There are a number of reasons for this, but a crucial one is to prevent the real burden of debt from increasing: it is nominal income rather than real income that matters for the servicing and repayment of outstanding debt. In short, if debt has to be serviced and paid back from stagnant or declining income, it will be harder to reduce the real value of debt.

Chart 19: Spain's deflationary GDP journey

(GDP deflators: the broadest measure of inflation in an economy)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis (FRED)

Chart 20: Spanish debt: Very little deleveraging

Source: Haver Analytics

In the absence of steady inflation, it is hard to prevent the real burden of debt - public and private - from rising. This is what has happened in Spain. Despite firms, households and the government trying to save more and spend less, and banks shrinking their balance sheets, Spain's overall debt level is higher than in 2008 (see Chart 20).

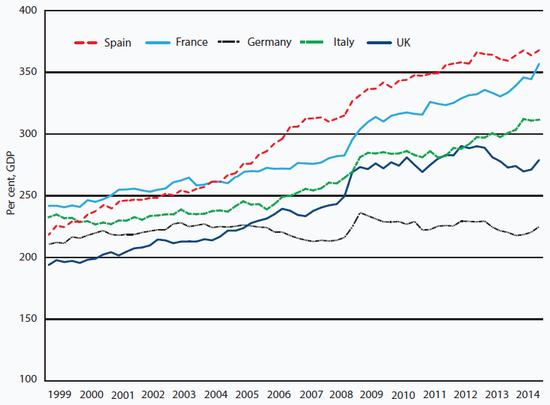

Excluding the financial sector gives a better indication of the weight of debt in an economy. Financial sector indebtedness is largely a function of the size of a country's financial sector. So long as banks are properly capitalised and capital markets firmly regulated, financial sector debt should not exert a drag on economic growth. However, high levels of non-financial, household and government debt combined with low inflation will depress demand. Spain has the highest debt of the big five EU economies once financial sector debt is excluded, and has not achieved any deleveraging at all (see Chart 21).

Chart 21: Spain's daunting debt burden

(General government, households and non-financial corporates)

Source: Haver Analytics

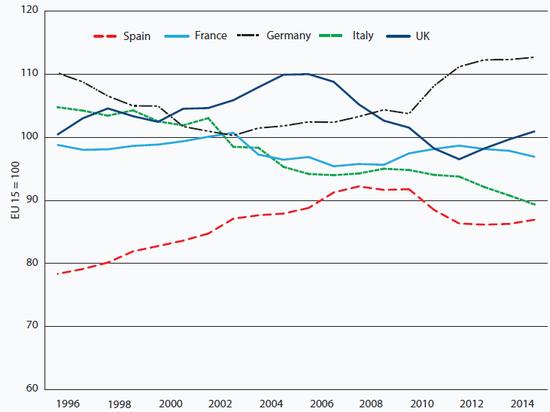

Chart 22: Real GDP per capita: Convergence interrupted

Source: Haver Analytics

Where now for Spain?

How is Spain likely to fare in the years ahead? Economic growth in poorer countries tends to outpace that in wealthier ones, as they adopt the best practices and technologies of richer countries. Spanish GDP per capita did converge steadily with the wealthier EU countries during the 15 years running up to 2008 (see Chart 22). Convergence then went into reverse during the crisis before starting to recover over the last year or so. The big question for Spain is whether it can outpace the rest of the eurozone by enough to bring about renewed convergence. Notwithstanding the current optimism over the country's economy, there are reasons to fear that Spain will remain relatively poor.

Debt: The first reason is debt, and the ongoing drag this will impose on the Spanish economy. Spanish debt is high and the efforts to reduce it are being thwarted by low inflation. While the fall in inflation over the last years has given a temporary boost to consumption, low inflation will be economically damaging. It will make it hard to reduce debt, which in turn risks holding back investment and consumption, which in turn will hit growth and inflation and hence the pace of deleveraging. To alleviate the debt burden, Spain needs much higher inflation, but it is doubtful that this will happen any time soon: there is a lot of spare capacity in the Spanish economy and unemployment will remain high for many years and continue to bear on prices. Meanwhile, the ECB has been complacent about eurozone inflation falling well below target for an extended period of time. And inflation in Spain is and will remain well below the average eurozone level. The Spanish economy needs a powerful monetary stimulus to raise inflation expectations, but that will not be forthcoming.

Real interest rates: This brings us onto the second reason: excessively high real interest rates. Notwithstanding its current growth spurt, the Spanish economy remains depressed and needs negative real interest rates if the recovery in consumption and investment is to be sustained. Unfortunately, real interest rates are and will remain too high for Spain. In a currency union with a common central bank, the real cost of borrowing tends to be either too high or too low for most of the participating regions most of time. A common eurozone interest rate means that the real cost of borrowing is highest in the weakest countries (where inflation is lowest), and lowest in the economically strongest (where inflation is highest), leading capital and skilled labour to concentrate in the richer regions. This happens in all currency unions. But whereas in the US, the UK or in Spain itself, the negative impact is cushioned by transfers of one kind or another between the participating regions or states, there are no such mechanisms in place in the eurozone. Moreover, Spain has little scope to impart a fiscal stimulus to offset the depressing impact of high real interest rates. The rules of the currency union preclude it; and even if they did not, the size of the country's deficit and the rapidly rising stock of public debt relative to GDP would give little room for stimulus.

Productivity: Spain requires considerably stronger productivity growth if Spanish living standards are to converge with wealthier EU countries. Stronger productivity relies on capital and labour inputs but also on the efficiency with which capital and labour are employed: so-called total factor productivity. The high real cost of borrowing combined with the burden of debt and weak consumption threaten to be a drag on investment. And there is little to suggest that investment is switching from lower-value production into higher value-added production, with the associated productivity gains. A high proportion of the jobs created over the last couple of years have been poorly-paid service sector employment, especially in tourism. Large numbers of educated young Spaniards are continuing to move abroad in search of work. If these workers eventually return to Spain, the long-term impact on Spanish productivity could be limited, or even positive, depending on the skills and experience they accumulate abroad. However, if those currently moving abroad stay there, Spain will suffer permanent damage to its economy.

The Spanish authorities sensibly shielded the education sector from the worst effects of austerity, but spending in that area remains well below the EU average as a proportion of GDP: only Greece and Italy spend less among the EU-15. Mass unemployment - much of it long-term - has damaged the country's skills base: workers outside the labour market quickly lose skills; and research shows that they are slower to regain skills the longer they are out of work.

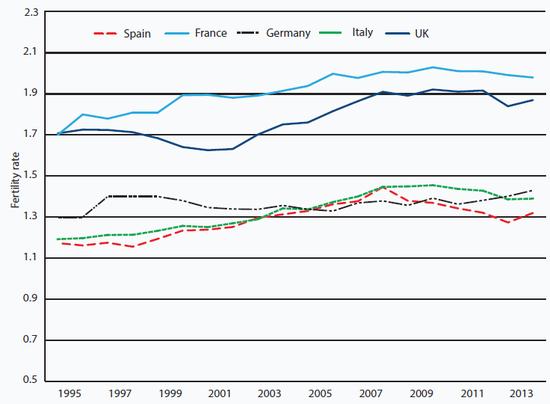

Demographics: Net immigration into Spain rose strongly in the run-up to the crisis, as large numbers of people moved there from Latin America, North Africa and elsewhere in the EU, attracted by plentiful jobs in the country's then booming construction industry. At the same time the country was still benefitting from the relatively healthy fertility rates of the 1980s. Since then inflows have fallen dramatically and outflows risen sharply, with the result that Spain has reverted to being a country of net emigration. The number of people leaving the country will no doubt ease as the labour market gradually recovers, but there is little reason to expect a return to large-scale immigration. The combination of one of the lowest birth rates in the world and net emigration means that the country's working age population is set to shrink rapidly (see Chart 23). This might not sound like a major problem for a country suffering from mass unemployment, but countries with shrinking workforces tend to suffer weak rates of economic growth.

Construction: Booming construction sector activity was a major factor behind Spain's rapid economic growth before the crisis, and this boom left the country with a long and nasty hangover. Construction accounted for almost 12 per cent of GDP by 2006 compared with around half that in France or the UK. Since then, Spanish construction activity has fallen to 5-6 per cent of GDP Although the construction sector appears to have bottomed out, there is little reason to expect anything but stagnation given Spain's demographics. There is still a large overhang of empty homes, some of which are being demolished but many of which will continue to weigh on the market. Infrastructure spending will also remain weak, partly as a result the fiscal pressures facing the Spanish government, but also because Spain's physical infrastructure is in good shape following heavy investment in the 20 years leading up to the crisis.

Chart 23: Fertility: One source of Spain's demographic problems

(Average number of children that would be born to a woman over her lifetime)

Source: Eurostat

Chart 24: Spain's current account balance: Positive, but only just

Source: Haver Analytics

Exports: If exports are to grow strongly it will have to be because Spanish businesses succeed in moving up the value chain. Unfortunately, there is little evidence of this happening. Spanish export performance since the depth of the crisis has been powered by low value-added sectors such as fuel and food. Export growth was partly the result of holding down wage costs, but also because fuels and other materials were exported rather than consumed locally, due to the collapse of domestic demand. This model is not sustainable: Spain cannot compete on the basis of low labour costs, while exports of fuels and materials will weaken as more domestic production is consumed locally, exposing the underlining weakness of Spain's external balance. Although domestic demand is still 12 per cent below pre-crisis levels and oil prices are low, the country's current account balance is barely positive (see Chart 24).

This suggests that the closing of the external deficit has been mostly cyclical rather than structural and that even a modest recovery in domestic demand will lead imports to rise more rapidly than exports, causing a renewed deficit.

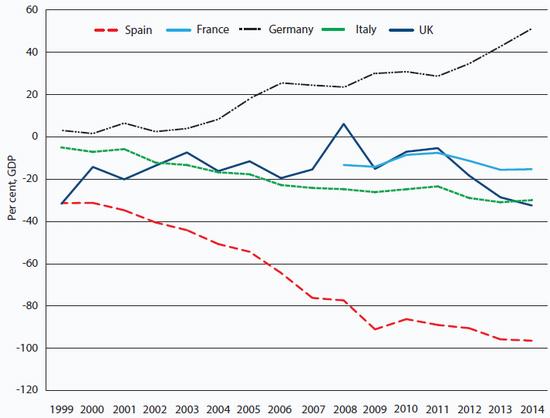

This is problematic for a number of reasons. With domestic demand set to be held back by high levels of debt, worsening demographics and fiscal austerity, net exports will need to be positive rather than negative, if Spain's economy is to grow robustly. Secondly, Spain's net external asset position (the country's overseas assets minus liabilities) is already hugely negative (see Chart 25). Further substantial current account deficits would lead to Spain becoming steadily more indebted to the rest of the world, an inauspicious position for a fast-ageing country to be in.

Chart 25: Net foreign assets

(Overseas assets minus value of domestic assets owned by foreigners)

Source: Haver Analytics

The next downturn: The final reason to be sceptical about Spain's convergence prospects is that the next downturn will be painful for the country. Too many eurozone policy-makers are mistaking a modest cyclical upturn in Spain, after a deep recession, for something more profound. Business cycles seem to be getting shorter and downturns deeper. The reasons for this are complicated but globalisation and increasingly complex financial linkages between countries appear to be playing a part. Nobody knows how long this eurozone cycle will last but we are probably already some way into it. Indeed, Spain is likely to enter the downturn having barely recovered from the previous recession, with high levels of public and private sector indebtedness, and unemployment well above pre-crisis levels. Crucially, it will have few policy tools at its disposal to combat a renewed weakening of domestic demand.

There is little reason to believe that the current upturn will be strong enough to undo the damage caused by the crisis. Real GDP could expand by 3 per cent this year and maybe 2.5 per cent next year (assuming that the eurozone does not relapse into another fullblown crisis). But this will not be enough to render debt sustainable (whether public or private), not least because inflation is set to remain extremely low due to the amount of slack in the Spanish economy. With the outlook for the eurozone economy poor and inflation low, it is unlikely that the ECB will have raised interest rates from the current level of close to zero before the next downturn. So the Spanish economy will not benefit from any interest rate cuts to counter the next downturn. The ECB should be able to employ more quantitative easing, but its effects might be exhausted by then.

Critically, the Spanish authorities will have little scope for fiscal stimulus to counter the weakness of private sector demand. The responsibility for back-stopping Spain's banks will still largely lie with Spain's fiscally-constrained government. And investors will be fully aware that a sovereign default could lead to a banking sector crisis of the kind seen in Greece.

Spain is likely to face the next recession with living standards still below pre-crisis levels, amid persistently strong support for populist parties. It is possible that the spectre of political instability in Spain and elsewhere will act as a catalyst for reform of the eurozone, ushering in more growth-orientated macroeconomic policies. But it is just as likely that it will not.

Conclusion

Spain is no poster child for fiscal austerity and structural reforms. The country's recent growth performance itself is less impressive than it appears at first sight, and owes a lot to an easing of fiscal and monetary policies and a (temporary) boost to consumption from lower inflation. There is little to suggest that structural reforms are prompting companies to move up the value-chain. Spain's relatively strong export performance largely reflects cost suppression and a strong rise in exports of fuels, raw materials and food, some which will be reversed as domestic demand picks up. And the flipside of cost suppression has been stagnant nominal GDP and hence little deleveraging: Spain remains a highly indebted economy. The country faces the daunting challenge of trying to improve productivity in a climate of persistently low inflation, high levels of domestic and external debt, restrictive macroeconomic policies and serious demographic problems.

Bar another full-blown eurozone crisis, Spain should gradually recover. But it is hard to see the country flourishing and Spanish living standards converging with the wealthier member-states of the eurozone, at least in the absence of substantive reforms of the currency union. Without much more growth orientated macroeconomic policies, and fiscal transfers to compensate poorer eurozone members for the impact of capital and skilled labour concentrating in the wealthier core, Spain faces plenty more pain.

Simon Tilford

Deputy director, Centre for European Reform

October 2015

| This document has been published on 11Mar16 by the Equipo Nizkor and Derechos Human Rights. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. |