| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

15Jan16

U.S.-Mexican Security Cooperation: The Mérida Initiative and Beyond

Back to top ContentsDrug Trafficking, Organized Crime, and Violence in Mexico

The Four Pillars of the Mérida Initiative

The Peña Nieto Administration's Security StrategyHigh Value Targeting

The Mérida Initiative: Funding and Implementation

Federal Operations in Violent States

Security and Justice Sector Reform

Community-Based Prevention

ImplementationPillar One: Disrupting the Operational Capacity of Organized Crime

Issues

Pillar Two: Institutionalizing Reforms to Sustain the Rule of Law and Respect for Human Rights in Mexico Pillar Three: Creating a "21st Century Border"Northbound and Southbound Inspections

Pillar Four: Building Strong and Resilient Communities

Preventing Border Enforcement Corruption

Mexico's Southern BordersMeasuring the Success of the Mérida Initiative

Outlook

Extraditions

Drug Production and Interdiction in Mexico

Human Rights Concerns and Conditions on Mérida Initiative Funding

Role of the U.S. Department of Defense in Mexico

Balancing Assistance to Mexico with Support for Southwest Border Initiatives

Integrating Counterdrug Programs in the Western HemisphereFigures

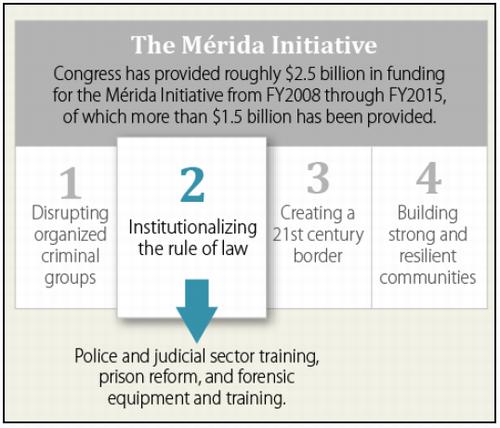

Figure 1. Current Status and Focus of the Mérida Initiative

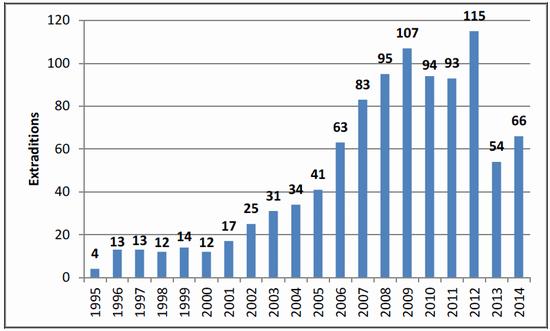

Figure 2. Individuals Extradited from Mexico to the United StatesTables

Table 1. FY2011-FY2016 Mérida Funding for Mexico

Appendixes

Appendix. U.S. Assistance to Mexico

Summary

Violence perpetrated by a range of criminal groups continues to threaten citizen security and governance in some parts of Mexico, a country with which the United States shares a nearly 2,000-mile border and more than $530 billion in annual trade. Although organized crime-related violence in Mexico generally declined since 2011, analysts estimate that it may have claimed more than 100,000 lives since December 2006. High-profile cases—particularly the enforced disappearance of 43 students in Guerrero, Mexico, in September 2014—have drawn attention to the problems of corruption and impunity for human rights abuses in Mexico.

Supporting Mexico's efforts to reform its criminal justice system is widely regarded as crucial for combating criminality and better protecting citizen security in the country. U.S. support for those efforts has increased significantly as a result of the development and implementation of the Mérida Initiative, a bilateral partnership launched in 2007 for which Congress appropriated nearly $2.5 billion from FY2008 to FY2015. U.S. assistance to Mexico focuses on (1) disrupting organized criminal groups, (2) institutionalizing the rule of law, (3) creating a 21st-century border, and (4) building strong and resilient communities. Newer areas of focus have involved bolstering security along Mexico's southern border and addressing drug production in Mexico. As of November 2015, more than $1.5 billion of Mérida Initiative assistance had been delivered.

Inaugurated to a six-year term in December 2012, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto has continued U.S.-Mexican security cooperation. U.S. intelligence has helped Mexico arrest top crime leaders, including Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzmán—the world's most wanted drug trafficker—in February 2014. Guzmán's July 2015 prison escape proved to be a major setback for bilateral efforts, but his January 2016 recapture may provide an opportunity to work together on extraditions and broader security efforts. The Mexican government is attempting to comply with international recommendations on preventing torture and enforced disappearances and is focused on meeting a 2008 constitutional mandate that Mexico transition to an accusatorial justice system by June 2016. As of December 2015, 6 states had fully implemented the system, and 26 had partially implemented it.

The 114th Congress is continuing to fund and oversee the Mérida Initiative and related domestic initiatives. While the FY2015 request for the Mérida Initiative was for $115 million, Congress ultimately provided $143.6 million in P.L. 113-235. Additional funds for Mexico are to support justice sector reform and Mexico's southern border program.

The Obama Administration's FY2016 request for the Mérida Initiative was for $119 million to help advance justice sector reform, modernize Mexico's borders (north and south), and support violence prevention programs. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113) would provide at least $147.5 million for Mexico, including $139 million in accounts that have funded the Mérida Initiative. The final amount destined for the Mérida Initiative is as yet unclear, however. The bill would place human rights withholding requirements on Foreign Military Financing for Mexico rather than Mérida Initiative assistance.

See also CRS In Focus IF10160, The Rule of Law in Mexico and the Mérida Initiative; CRS Report R43001, Supporting Criminal Justice System Reform in Mexico: The U.S. Role; and CRS In Focus IF10215, Mexico's Recent Immigration Enforcement Efforts.

Introduction

For more than a decade, violence and crime perpetrated by warring criminal organizations has threatened citizen security and governance in parts of Mexico. While the illicit drug trade has long been prevalent in Mexico, an increasing number of criminal organizations are fighting for control of smuggling routes into the United States and local drug markets. This violence resulted in more than 60,000 deaths in Mexico during the Felipe Calderón Administration (December 2006-November 2012). Another 20,000 organized crime-related deaths occurred in the first two years of the Enrique Peña Nieto Administration. |1| The still unresolved case of 43 missing students who disappeared in Iguala, Guerrero, in September 2014 has drawn attention to the issues of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances involving security forces.

U.S.-Mexican cooperation to improve security and the rule of law in Mexico has increased significantly as a result of the Mérida Initiative, a bilateral partnership developed by the George W. Bush and Calderón governments. Between FY2008 and FY2015, Congress appropriated almost $2.5 billion for Mérida Initiative programs in Mexico (see Table 1). Some $1.5 billion worth of training, equipment, and technical assistance had been provided to Mexico as of November 2015. Mexico, for its part, has invested some $79 billion of its own resources on security and public safety. |2| While bilateral efforts have yielded some results, the weakness of Mexico's criminal justice system may have limited the effectiveness of those efforts.

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) took office in December 2012 vowing to reduce violence in Mexico and adjust the current U.S.-Mexican security strategy to focus on violence prevention. While Mexico's public relations approach to security issues has changed, most analysts maintain that Peña Nieto has quietly adopted an operational approach similar to that of former president Calderón. That approach, commonly referred to as the "kingpin" strategy, has focused on taking out the top and mid-level leadership of Mexico's DTOs. The February 2014 capture of notorious Sinaloa leader Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzmán to be a high point for this government; his subsequent escape from a maximum security prison near Mexico City served as perhaps one of its lowest points.

The Mexican government has continued law enforcement and intelligence-sharing with U.S. counterparts; it has also bolstered security along its southern border. |3| Mexican officials have recently agreed to develop a bilateral plan to combat the cultivation, production, and trafficking of heroin. |4| One key concern for U.S. policymakers is whether the Mexican government will be able to hold Guzmán (who was recaptured on January 8, 2016) securely in the same prison from which he escaped and then extradite him swiftly to the United States—a source of tension in U.S.-Mexican relations. Another is whether Guzmán's recapture, which was supported by U.S. intelligence, will lead to closer security cooperation moving forward.

Congress provided $139 million in Mérida Initiative accounts in the FY2016 Consolidated Appropriations bill (P.L. 114-113) and will soon be considering the Obama Administration's FY2017 budget request. Congress may analyze how progress under the Mérida Initiative is being measured; how U.S. funds have been used to advance Mexico's police and judicial reform efforts; and the degree to which U.S. programs in Mexico complement other U.S. counterdrug and border security efforts. Congress may seek to ensure that Mérida Initiative funds support drug eradication and interdiction programs given recent rises in heroin and methamphetamine production in Mexico. Compliance with Mérida's human rights conditions may continue to be closely monitored, particularly since the State Department's decision not to submit a human rights progress report for Mexico required in FY2014 appropriation legislation (P.L. 113-76) resulted in Mexico losing $5.5 million in U.S. assistance.

This report provides a framework for examining the current status and future prospects for U.S.Mexican security cooperation. It begins with a brief discussion of security challenges in Mexico and Mexico's security strategy. It then provides updated information on congressional funding and oversight of the Mérida Initiative before delving into its four pillars. The report concludes by raising policy issues that Congress may wish to consider as it continues to fund and oversee the Mérida Initiative and broader U.S.-Mexican security cooperation.

Background

Drug Trafficking, Organized Crime, and Violence in Mexico |5|

Countering the movement of illegal drugs from Mexico into the U.S. market has remained a top U.S. drug control priority for decades. Mexico is the main supplier to the U.S. market of heroin, methamphetamine, and marijuana and a major transit country for cocaine sold in the United States. Marijuana remains the most widely abused drug in the United States, with much of the supply coming from Mexico, although Mexican marijuana is "inferior to the marijuana produced domestically." |6| In contrast, more Mexico-produced methamphetamine is being used in the United States than U.S.-produced product. Methamphetamine seizures at the southwest border have increased 233% from 2009 to 2013. |7| There has also been particular concern about the increasing availability of Mexican-produced heroin in the United States, including in eastern states where Colombian-produced heroin used to predominate. |8| The amount of heroin seized along the U.S.Mexico border increased by 296% from 2008 to 2013. |9|

Mexican transnational criminal organizations (TCOs), often in alliance with U.S. national and local gangs, continue to dominate the U.S. drug market. According to Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), 10 major Mexican TCOs operate in the United States, but the Sinaloa organization has the widest reach into U.S. cities and is the biggest supplier. |10| Sinaloa has been cited as a primary source of Mexican heroin bound for the United States. |11|

Organized crime-related homicides in Mexico have declined each year since 2011, but may have risen this year. |12| Crime groups have vied for control of illicit routes into the United States and for control over local drug distribution networks. Drug abuse in Mexico is most prevalent in places where criminal organizations have been paying their workers in product rather than in cash. Mexico's criminal organizations are continuing to fragment and diversify away from drug trafficking, furthering their expansion into activities such as oil theft, alien smuggling, and human trafficking. Much of the crime—particularly extortion—is parasitic on localities and businesses. According to the State Department's 2015 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, reports of extortion and kidnapping have increased in recent years and have stayed elevated.

The dominant TCOs have been in flux this year, capping many years of change. Observers maintain that the Sinaloa organization continues to dominate much of the drug trade in Mexico; it controls roughly 40% to 60% of Mexico's drug trade, according to several estimates. Nevertheless, there are 10 Mexican TCOs that traffic drugs into the United States. |13| In addition to the larger TCOs, analysts contend that there has been an explosion of smaller crime groups, perhaps as many as 60 to 200, many of which may not operate outside of their own regions. |14|

The Peña Nieto Administration's Security Strategy

Upon taking office, President Peña Nieto made violence reduction one of his priorities. The six pillars of his security strategy include (1) planning; (2) prevention; (3) protection and respect of human rights; (4) coordination; (5) institutional transformation; and (6) monitoring and evaluation. Peña Nieto has taken action on two priority proposals on security: launching a national crime prevention plan and establishing a unified code of criminal procedures to cover judicial procedures for the federal government and the states. Other key proposals—creating a large national gendarmerie (militarized police) and a strong central intelligence agency—have been either delayed or watered down. |15|

Despite criticism from human rights groups, there are no plans to remove military forces from public security functions. The government is under pressure, however, to comply with recommendations on preventing torture and enforced disappearances from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and others. |16| President Peña Nieto has submitted legislation to combat both of those crimes to the Mexican Congress that are to be considered this year.

Mexico's Attorney General's office is in the process of developing a new anti-drug strategy. It remains to be seen whether the Mexican Supreme Court's ruling in support of a person's right to grow and use marijuana recreationally will influence the country's traditionally strict prohibitionist stance. |17| The government has launched a national dialogue on marijuana policy in response to calls from some sectors to revisit its position, particularly given moves in some U.S. states to allow marijuana consumption for medicinal and recreational purposes. There may also be consideration of legislation to liberalize marijuana use in Mexico's Congress this year. However, more than 60% of Mexicans polled disagreed with the Supreme Court's ruling. |18|

High Value Targeting

The capture of "El Chapo" Guzmán in February 2014 was widely seen as evidence of continued U.S. intelligence assistance and cooperation with Mexico's security forces after the government's initial preference to limit U.S. involvement in law enforcement operations. It symbolized the capstone of Peña Nieto's "kingpin" strategy, which began under the Calderón government and focused on taking out the top and mid-level leadership of Mexico's largest TCOs. According to the Mexican government, 98 of the 122 top criminal targets had been arrested or killed during law enforcement operations as of January 2016 (with El Chapo's recapture). Few have been successfully prosecuted, however, and the pace of arrests slowed significantly in the past year. |19| While some critics fault the kingpin strategy for causing turf battles and a proliferation of crime groups in Mexico, others maintain that is the only viable strategy to deal with large criminal groups that have committed serious crimes with relative impunity.

Federal Operations in Violent States

President Peña Nieto has also maintained Calderón's reactive approach of deploying federal forces—including the military and the gendarmerie—to areas where crime surges. In the state of Michoacan, the emergence of armed civilian "self-defense groups" that clashed with crime groups prompted a federal intervention that yielded mixed results in 2013. |20| New contingents of federal forces are being deployed there again at the request of the new PRI governor. Tamaulipas has been divided into four zones overseen by Mexican military and federal police forces that have captured drug traffickers, yet violence has continued. Federal forces that had been operating in the state of Guerrero did not intervene to prevent six killings and the enforced disappearances of 43 students in Iguala, Guerrero, by local police collaborating with criminal groups in September 2014. In fact, some federal police may have participated in the disappearances. |21| In October 2014, Mexico's National Human Rights Commission issued a report concluding that at least 12 people had been killed execution-style by the Mexican military in Tlatlaya, Mexico, on July 1, 2014. |22|

Security and Justice Sector Reform

In addition to enacting a unified code of criminal procedure, the Peña Nieto government has allocated additional funds to support implementation of judicial reforms enacted in 2008. As per those constitutional reforms, Mexico has until June 2016 to replace its trial procedures in federal and state courts, moving from a closed-door process based on written arguments presented to a judge to an adversarial public trial system with oral arguments and the presumption of innocence. These changes are expected to make the system more transparent and impartial. Through alternative dispute resolution, the system can also become more flexible and efficient.

As of October 2015, six states had fully implemented the new system, and 25 had partially implemented the new system. |23| Sonora began its implementation process in mid-December 2015. Many states operating under the new system have reduced the length and costs associated with trials, as well as the use of preventive detention. Significant work remains to be done, however, particularly to increase the investigative capacity of police. |24|

Mexico's federal structure has thus far made efforts at police reform extremely challenging. The Calderón government made strides in increasing the size, training, and equipment of the federal police, yet that force has still been accused of serious crimes. Vetting of police at all levels has increased, yet many states and municipalities have kept officers who failed those exams on their payrolls. Some states have recruited entirely new police forces (such as the northern state of Nuevo Leon), while others have had their state force (Durango) absorb most municipal police. Protocols on the use of force for federal police have been enacted, as well as policing standards.

In November 2014, President Peña Nieto proposed 10 actions to improve the rule of law. One of those actions was the mando único (unified command)—a constitutional reform that would require states to remove the command of police forces from municipalities and to place it at the state level. This plan aims to reduce police corruption and improve coordination with federal forces. Many experts question the notion that state forces are any less corrupt and maintain that this change will not prevent abuses or strengthen accountability. A constitutional reform on mando único has not moved forward; neither have most of the rest of Peña Nieto's proposals save his promise to launch a federal operation in the "Tierra Caliente" region encompassing Guerrero, Morelos, and Michoacán and to create a national emergency line. |25|

Community-Based Prevention

Upon taking office, President Peña Nieto launched a National Crime and Violence Prevention program based, in part, on lessons learned from bilateral efforts in cities such as Cuidad Juárez that have been supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development. Peña Nieto budgeted $19 billion for prevention efforts in 2013-2014, but the program's budget has been cut since, possibly due to austerity necessitated by declining oil revenues. Federal funds are providing a variety of interventions in municipalities with high crime rates that also exhibit social risk factors. The program has been criticized by Mexican analysts for lacking a rigorous methodology for selecting and evaluating the communities and interventions that it is funding. |26| The program's director was removed in November 2015 as he was being investigated for corruption, and many key initiatives on prevention remain stalled and without adequate funding.

The Mérida Initiative: Funding and Implementation |27|

In October 2007, the United States and Mexico announced the Mérida Initiative, a package of U.S. assistance for Mexico and Central America that would begin in FY2008. |28| The Mérida Initiative was developed in response to the Calderón government's unprecedented request for increased U.S. support and involvement in helping Mexico combat drug trafficking and organized crime. As part of the Mérida Initiative's emphasis on shared responsibility, the Mexican government pledged to tackle crime and corruption and the U.S. government pledged to address domestic drug demand and the illicit trafficking of firearms and bulk currency to Mexico. |29| A January 2016 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report concluded that 70% of firearms seized by Mexican authorities between 2009 and 2014 came from the United States. |30|

Whereas U.S. assistance initially focused on training and equipping Mexican security forces for counternarcotic purposes, it has shifted toward addressing the weak government institutions and societal problems that have allowed the drug trade to thrive in Mexico. The strategy now focuses more on institution-building than on technology transfers and broadens the scope of bilateral efforts to include economic development and community-based social programs. There is also increasing funding at the sub-national level for Mexican states and municipalities.

In May 2013, Presidents Obama and Peña Nieto reaffirmed their commitments to the Mérida Initiative's four-pillar strategy during President Obama's trip to Mexico. In August 2013, the U.S. and Mexican governments then agreed to focus on justice sector reform, money laundering, police and corrections professionalization at the federal and state level, border security both north and south, and piloting approaches to address root causes of violence. The U.S. and Mexican governments held the third Security Cooperation Group meeting during the Peña Nieto government in Mexico City in October 2015 to oversee the Mérida Initiative and broader security cooperation efforts. Issues such as how to combat drug trafficking—including opium poppy production in Mexico—were on the agenda. |31|

Congress has played a major role in determining the level and composition of Mérida Initiative funding for Mexico. From FY2008 to FY2015, Congress appropriated nearly $2.5 billion for Mexico under the Mérida Initiative (see Table 1 for Mérida appropriations and Table A-1 in Appendix for overall U.S. assistance to Mexico since FY2010). In the beginning, Congress included funding for Mexico in supplemental appropriations measures in an attempt to hasten the delivery of certain equipment. Congress has also earmarked funds in order to ensure that certain programs are prioritized, such as efforts to support institutional reform. From FY2012 onward, funds provided for pillar two have exceeded all other aid categories. In FY2015, Congress provided $28.6 million above the Administration's request, with additional funding for justice sector programs and efforts to help secure Mexico's southern border.

Figure 1. Current Status and Focus of the Mérida Initiative

Source: U.S. Department of State.

In 2015, some Members of Congress have asked Mexico to intensify its eradication and interdiction efforts and may direct additional U.S. assistance to that effort through pillar one of the Mérida Initiative. |32| Others may oppose that position.

Congress has sought to influence human rights conditions and encourage efforts to combat abuses and impunity in Mexico by placing conditions on Mérida Initiative assistance. From FY2008 through FY2015, Congress directed that 15% of certain assistance provided to Mexican military and police forces would be subject to certain human rights conditions. Congress has also withheld funding due to human rights concerns. The conditions included in the FY2014 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 113-76) and in the FY2015 Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act (P.L. 113-235) are slightly different than in previous years. There are no human rights conditions on Mérida Initiative accounts in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113).

The Obama Administration's FY2016 request for the Mérida Initiative was for $119 million to help advance justice sector reform, modernize Mexico's borders (north and south), and support violence prevention programs. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113) provides at least $147.5 million for Mexico, including $139 million in accounts that have funded the Mérida Initiative (INCLE and ESF). The final amount destined for the Mérida Initiative is as yet unclear. However, the House Appropriations Committee-passed version of the FY2016 Foreign Operations measure (H.R. 2772), which was integrated into P.L. 114-113, stated that ESF aid is "only for programs for rule of law and human rights, justice and security, good governance, civil society, education, private sector competitiveness and economic growth." In recent years, the State Department has reprogrammed some ESF funding for global climate change programs.

Table 1. FY2011-FY2016 Mérida Funding for Mexico

($ in millions)

Account FY2011 FY2012 FY2013 FY2014 FY2015 Estimate FY2016 Request FY2016 (est.) ESF 18.0 33.3 32.1 35.0¬ 33.6b 39.0 39.0 INCLE 117.0 248.5 195.1 148.1 110.0 80.0 100.0 FMF 8.0 N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Total 143.0 281.8 227.2 194.2 143.6 119.0 139.0 Sources: U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Operations FY2008-FY2016.

Notes: ESF=Economic Support Fund; FMF=Foreign Military Financing; INCLE=International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement.

a. $11.8 million of ESF was designated for Global Climate Change (GCC) programs in Mexico.

b. $12.5 million was designated for GCC programs.Implementation

For the past several years, Congress has maintained an interest in ensuring that Mérida-funded equipment and training is delivered efficiently. After initial delays, deliveries accelerated in 2011, with more than $500 million worth of equipment, training, and technical assistance provided. As of the end of Calderón's term (November 2012), $1.1 billion worth of assistance had been provided. That total included roughly $873.7 million in equipment (including 20 aircraft |33| and more than $100 million in non-intrusive inspection equipment) and $146.0 million in training.

For most of 2013, delays in implementation occurred largely due to the fact that the Peña Nieto government was still honing its security strategy and determining the amount and type of U.S. assistance needed to support that strategy. The initial procedure the government adopted for processing all requests from Mexican ministries for Mérida Initiative funds through the interior ministry also contributed to delays. By November 2013, the State Department and Mexican foreign affairs and interior ministries had agreed to a new, more agile process for approving new Mérida Initiative projects. The governments have agreed to more than 100 new projects worth more than $600 million. As of November 2015, deliveries stood at roughly $1.5 billion.

U.S. assistance has increasingly focused on supporting efforts to strengthen institutions in Mexico through training and technical assistance. U.S. funds support training courses offered in new or refurbished training academies for customs personnel, corrections staff, canine teams, and police (federal, state, and local). |34| Some of that training is designed according to a "train the trainer" model in which the academies train instructors who in turn are able to train their own personnel. Despite the significant number of justice sector officials who have been trained over the past several years, high turnover rates within Mexican criminal justice institutions have limited the impact of U.S. training programs.

The Four Pillars of the Mérida Initiative

Pillar One: Disrupting the Operational Capacity of Organized Crime

U.S. assistance appropriated during the first phase of the Mérida Initiative (FY2008-FY2010) enabled the purchase of equipment to support the efforts of federal security forces engaged in anti-TCO efforts. That equipment included $590.5 million worth of aircraft and helicopters, as well as forensic equipment for the Federal Police and Attorney General's respective crime laboratories. U.S.-funded non-intrusive inspection equipment (more than $125 million) and 340 canine teams have also helped Mexican forces interdict illicit flows of drugs, weapons, and money. In response to rising heroin production in Mexico, the State Department has offered to provide Mexico with assistance in drug crop eradication and interdiction efforts and to develop a bilateral plan to stop heroin production and trafficking. Some Members of Congress would also like to see assistance for interdiction further increased. |35|

The Mexican government has increasingly been conceptualizing the drug-trafficking organizations (DTOs) as for-profit corporations. Consequently, its strategy, and U.S. efforts to support it, has begun to focus more attention on disrupting the criminal proceeds used to finance DTOs' operations, although much more could be done in that area. |36| In August 2010, the Mexican government imposed limits on the amount of U.S. dollars that individuals can exchange or deposit each month; restrictions on cash deposits by businesses in the northern border region were eased in September 2014. |37| In October 2012, the Mexican Congress approved an anti-money laundering law that established a financial crimes unit within the Attorney General's office (PGR), subjected additional industries vulnerable to money laundering to new reporting requirements, and created new criminal offenses for money laundering. Mérida assistance has provided $20 million in equipment, software, training, and technical assistance to the financial intelligence unit, which is helping that unit analyze data on suspicious transactions and prepare cases for referral to the PGR.

As mentioned, the DTOs are increasingly evolving into poly-criminal organizations, perhaps as a result of drug interdiction efforts cutting into their profits. As a result, many have urged the U.S. and Mexican governments to focus on combating other types of organized crime, such as kidnapping and human smuggling. Some may therefore question whether the funding provided under the Mérida Initiative is being used to adequately address all forms of transnational organized crime.

Cross-border law enforcement operations and investigations have been suggested as possible areas for increased cooperation. Of note, there already exist a number of U.S.-Mexican law enforcement partnerships, both formal and informal. For instance, Mexican federal police have participated in the Border Enforcement Security Task Force (BEST) initiative, led by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). |38| In September 2015, ICE also launched a Transnational Criminal Investigative Unit composed of vetted Mexican federal police to work on cases of alien smuggling, human trafficking, and other crimes. The State Department and the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) are working with Mexican law enforcement officials to develop a strategy to address dismantle smuggling networks and a communication strategy to raise awareness on the risks of smuggler recruitment.

U.S. law enforcement and intelligence officials support Mexican intelligence-gathering efforts in northern and southern Mexico, and U.S. drones operating along the U.S.-Mexico border gather information that is shared with Mexican officials. A $13 million cross-border telecommunications system for sister cities along the U.S.-Mexico border that was funded by the Mérida Initiative is facilitating information-sharing among law enforcement in that region. U.S. aid has helped federal, state, and municipal forces form joint intelligence task forces throughout the country.

As Mexico receives an estimated $75 million in U.S. equipment and training to secure its southern borders |39| with Guatemala and Belize, the need for more regional partnerships with those countries has also arisen. (See "Mexico's Southern Borders" below.)

Pillar Two: Institutionalizing Reforms to Sustain the Rule of Law and Respect for Human Rights in Mexico |40|

Violence and criminality have overwhelmed Mexico's law enforcement and judicial institutions, with record numbers of arrests rarely resulting in successful convictions. With impunity rates hovering around 82% for homicide and even higher for other crimes, |41| experts maintain that it is crucial for Mexico to implement the aforementioned judicial reforms passed in the summer of 2008 and to focus on fighting corruption at all levels of government. Increasing cases of human rights abuses committed by authorities at all levels, as well as Mexico's inability to investigate and punish those abuses, are also pressing concerns.

Reforming the Police

Mexican police are tasked with combating criminal groups that are constantly evolving and extremely dangerous. Police roles are changing under the new adversarial justice system, which requires them to prepare investigations that can be challenged in public oral trials and to serve as witnesses in court. Endemic corruption, abuses of power, a reliance on evidence gathered through confessions (sometimes obtained through torture) rather than forensic evidence, extremely low levels of popular trust, and poor relations with prosecutors have hindered police's ability to combat crime. Low salaries, poor working conditions, and limited opportunities for career advancement have hindered recruiting and retention in some states and municipalities as well.

The Calderón Administration increased police budgets, raised selection standards, and enhanced police training and equipment at the federal level. It also created a national database, through which police at all levels can share information and intelligence, and accelerated implementation of a national police registry. Two laws passed in 2009 created a federal police force under the former secretariat for public security or SSP and another force under the PGR, both with some investigative functions. Whereas initiatives to recruit, vet, train, and equip the federal police advanced (with support from the Mérida Initiative |42|) during the Calderón government, efforts to build the PGR's police force lagged. The Peña Nieto government has placed the federal police and the SSP under the authority of the interior ministry, created a new gendarmerie within the federal police, and put the PGR's police within its new investigative agency. U.S. training has been offered to each of those entities. |43|

State and local police reform has lagged well behind federal police reform efforts. A public security law codified in January 2009 established vetting and certification procedures for state and local police to be overseen by the national public security system (SNSP). Federal subsidies have been provided to state and municipal units whose officers meet certain standards. Some $24 million in U.S. equipment and training assistance has supported implementation of codified standards, vetting of law enforcement, the establishment of internal affairs units, and centralization of personnel records. U.S. assistance is also helping police institutions adopt common standards, create career paths, and deter police from engaging in corruption. As of May 2015, roughly 14,100 of 134,600 Mexican municipal police failed vetting exams and another 17,000 state police failed as well. |44| According to Causa en Comun, a Mexican civil society organization that has received U.S. funds, the states of Baja California Sur, Michoacan, Nayarit, Tlaxcala, and Zacatecas have not fulfilled their requirements with respect to the 2009 law.

The establishment of unified state police commands (mando único) that could potentially absorb municipal police forces has been debated in Mexico for years. |45| The Mexican Congress failed to pass a constitutional reform proposal put forth by the Calderón government to establish unified state police commands. Nevertheless, President Peña Nieto has signed agreements to help 17 states move in that direction and introduced his own constitutional reform proposal on that issue. Mexico's interior minister and its governor's conference have called for the constitutional adoption of mando único. |46| Some mayors in Morelos have refused to do so, prompting a political struggle in an area of that state where a mayor was assassinated a day after taking office. |47|

The outcome of the police reform efforts could have implications for U.S. initiatives to expand Mérida assistance to state and municipal police forces, particularly as the Mexican government determines how to organize and channel that assistance. Mérida funding has supported state-level academies and training courses for state and local police in officer safety, securing crime scene preservation, investigation techniques, leadership and supervision, and law enforcement intelligence-gathering. Training efforts have also focused on helping police work with forensics analysts and prosecutors to investigate crimes and serve as expert witnesses during oral trials.

In order to complement these efforts, some analysts maintain that it is important to provide assistance to civil society and human rights-related nongovernmental organizations in Mexico in order to strengthen their ability to monitor police conduct and provide input on policing policies. Some maintain that citizen participation councils, combined with internal control mechanisms and stringent punishments for police misconduct, can have a positive impact on police performance and police-community relations. Others have mentioned the importance of establishing citizen observatories to develop reliable indicators to track police and criminal justice system performance, as has been done in some states. As these external oversight programs begin to emerge within Mexico, the State Department intends to assist through providing Mérida funding for their development and implementation.

Reforming the Judicial and Penal Systems

The Mexican judicial system has been widely criticized for being opaque, inefficient, and corrupt. It is plagued by long case backlogs, a high pre-trial detention rate, and an inability to secure convictions. |48| The vast majority of drug trafficking-related arrests that have occurred over the last several years have not resulted in successful prosecutions. The PGR has also been unable to secure charges in many high-profile cases involving the arrests of politicians accused of collaborating with organized crime.

Mexican prisons, particularly at the state level, are also in need of significant reforms. Increasing arrests have caused prison population to expand significantly, as has the use of preventive detention. Those suspected of involvement in organized crime can be held by the authorities for 40 days without access to legal counsel, with a possible extension of another 40 days, a practice known as "arraigo" (pre-charge detention) that has led to serious abuses by authorities. |49| The government continues to say arraigo is necessary to facilitate some types of investigations, although reports that its usage has decreased by 90% in 2015 as compared to 2012. |50| Many inmates (perhaps 40%) are awaiting trials, as opposed to serving sentences. |51| In October 2015, Mexico's Human Rights Commission estimated that the country's prisons were at 27% over capacity. Prison breaks and riots are particularly common in state facilities. However, the July 2015 escape by "El Chapo" Guzmán from a maximum security federal prison revealed the dangers posed by corrupt officials inside federal facilities as well. |52| INL provides training, technical assistance, and equipment to help reform federal and state penitentiary systems and obtain independent accreditation from the American Correctional Association (ACA).

Mexico is six months away from the June 2016 deadline (established in 2008 constitutional reforms) to replace its trial procedures at the federal and state level. Under the reform, Mexico will move from a closed-door process based on written arguments to a public trial system with oral arguments and the presumption of innocence until proven guilty. While justice reform efforts at the federal level lagged during the Calderón government, President Peña Nieto has devoted more political capital and resources to support the process. Peña Nieto shepherded a unified code of criminal procedure to cover the entire judicial system through the Mexican Congress in February 2014; it was promulgated in March 2014. The federal government and Mexican states have been building new courtrooms, retraining current legal professionals, updating law school curricula, and improving forensic technology—a difficult and expensive undertaking.

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is implementing an $81 million rule of law program that provides assistance to Mexican state and federal authorities in all 31 Mexican states and the Federal District, and to civil society organizations that monitor and support reform efforts. Activities provide comprehensive technical assistance to support effective transition to the new criminal justice system. They include strengthening the legal framework; improving prosecutor and judicial capacity and coordination; public awareness and outreach regarding the reforms; building analytical capacity in justice sector institutions (to better track progress); and supporting victims' assistance and access to justice, particularly for women. USAID also supports training for private lawyers, professors, and bar associations to ensure that legal curricula and technical standards are consistent with the new accusatory, adversarial system.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) has supported judicial reform at the federal level, including providing technical assistance to the Mexican Congress during the drafting and adoption of a unified criminal procedure code through its Office of Overseas Prosecutorial Development and Training (OPDAT). In 2011 -2012, DOJ worked with the PGR to design and implement a national training program (Project Diamante) through which approximately 9,000 prosecutors, investigators, and forensic experts were trained in the accusatorial system. The PGR is now using Diamante-certified instructors and jointly developed curriculum to transition its personnel and operations to the accusatorial system in 21 federal branches in 2015 and the remaining 11 in 2016. OPDAT is also working with the PGR to commence with previously stalled specialized training programs for prosecutors in anti-money laundering, trafficking in persons, and anti-kidnapping cases.

DOJ also implemented a capacity building program in Puerto Rico for regional federal judges, through which OPDAT Mexico trained over 250 federal judges. Based on the training program in Puerto Rico, OPDAT Mexico is now beginning a program for approximately 600 Mexican federal judges in order to reach more justice operators in time for the 2016 deadline for implementation of the new accusatorial system.

The U.S. Congress has expressed support for the continued provision of U.S. assistance for judicial reform efforts in Mexico in appropriations legislation, hearings, and committee reports. Congressional funding and oversight of judicial reform programs in Mexico is likely to continue for many years. Over time, Congress may consider how best to divide funding between the federal and state levels; how to sequence and coordinate support to key elements within the rule of law spectrum (police, prosecutors, courts); and how the efficacy of U.S. programs is being measured.

Pillar Three: Creating a "21st Century Border"

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is charged with facilitating the flow of people, commerce, and trade through U.S. ports of entry while securing the border against threats. While enforcement efforts at the southwest border tend to focus on illegal migration and cross-border crime, commercial trade crossing the border also poses a potential risk to the United States. Since the North American Free Trade Agreement took effect in 1994, U.S.-Mexico trade has dramatically increased, while investments in port infrastructure and staffing of customs officials along the border have not, until recently, been made. Particularly since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, there have been significant delays and unpredictable wait times at the U.S.-Mexico border. Concerns about those delays has increased in recent years, since roughly 80% of U.S.-Mexico trade must pass through a port of entry along the southwest border, often more than once, as manufacturing processes between the two countries have become highly integrated.

On May 19, 2010, the United States and Mexico declared their intent to collaborate on enhancing the U.S.-Mexican border as part of pillar three of the Mérida Initiative. A Twenty-First Century Border Bilateral Executive Steering Committee (ESC) |53| has met eight times since then to develop bi-national action plans and oversee implementation of those plans. The plans are focused on setting measurable goals within broad objectives: coordinating infrastructure development, expanding trusted traveler and shipment programs, establishing pilot projects for cargo pre-clearance, improving cross-border commerce and ties, and bolstering information sharing among law enforcement agencies. In December 2015, the ESC reported that their efforts had resulted in new facilities at the San Isidro-Tijuana port for southbound screenings, a cross-border pedestrian bridge at the Tijuana airport, the opening of the Brownsville-Matamoros International Railway Bridge, and the creation of a "Cargo Pre-Inspection Program." |54| That program, which enables U.S. and Mexican customs officials to work together at three locations along the shared border to clear goods before they arrive at a port of entry, aims to minimize the double inspection of shipments. It was enabled by Mexico's recent passage of a law enabling U.S. customs and immigration officials to bear arms in Mexico. |55|

Northbound and Southbound Inspections |56|

One element of concern regarding enhanced bilateral border security efforts is that of southbound inspections of people, goods, vehicles, and cargo. In particular, both countries have acknowledged a shared responsibility in fueling and combating the illicit drug trade. Policymakers may question who is responsible for performing northbound and southbound inspections in order to prevent illegal drugs from leaving Mexico and entering the United States and to prevent dangerous weapons and the monetary proceeds of drug sales from leaving the United States and entering Mexico. Further, if this is a joint responsibility, it is unclear how U.S. and Mexican border officials will divide the responsibility of inspections to maximize the possibility of stopping the illegal flow of goods while simultaneously minimizing the burden on the legitimate flow of goods and preventing the duplication of efforts.

In addition to its inbound/northbound inspections, the United States has undertaken steps to enhance its outbound/southbound screening procedures. Currently, DHS is screening 100% of southbound rail shipments for illegal weapons, cash, and drugs. Also, CBP scans license plates along the southwest border with the use of automated license plate readers. Further, CBP employs non-intrusive inspection (NII) systems—both large-scale and mobile—to aid in inspection and processing of travelers and shipments.

Historically, Mexican Customs had not served the role of performing southbound (or inbound) inspections. As part of the revised Mérida Initiative, CBP has helped to establish a Mexican Customs training academy to support professionalization and promote the Mexican Customs' new role of performing inbound inspections. Additionally, CBP is assisting Mexican Customs in developing investigator training programs and the State Department has provided over 148 canines to assist with the inspections. |57|

Preventing Border Enforcement Corruption

Another point that policymakers may question regarding the strengthening of the Southwest border is how to prevent the corruption of U.S. and Mexican border officials who are charged with securing the border. Data from a 2012 GAO report can provide a snapshot of corruption involving Southwest border officials:

From fiscal years 2005 through 2012, a total of 144 [CBP] employees were arrested or indicted for corruption-related activities, including the smuggling of aliens or drugs... About 65 percent (93 of 144 arrests) were employees stationed along the southwest border. |58|

To date, the 21st century border pillar has not directly addressed this issue of corruption. Congress may consider whether preventing, detecting, and prosecuting public corruption of border enforcement personnel should be a component of the border initiatives funded by the Mérida Initiative. Congress may also decide whether to increase funding—as part of or separately from Mérida funding—for the vetting of new and current border enforcement personnel.

Mexico's Southern Borders |59|

Policymakers may also seek to examine a relatively new element under pillar three of the Mérida Initiative that involves U.S. support for securing Mexico's porous and insecure southern borders with Guatemala and Belize. With U.S. support, the Mexican government has been implementing a southern border security plan since 2013 that has involved the establishment of 12 advanced naval bases on the country's rivers and three security cordons that stretch more than 100 miles north of the Mexico-Guatemala and Mexico-Belize borders. Mexico's National Institute of Migration (INAMI) agents have taken on a new enforcement directive alongside federal and state police forces. These unarmed agents have worked with the military and the police to increase immigration enforcement efforts along known migrant routes. While several U.S. officials have praised Mexico's efforts, human rights groups have criticized Mexico for abuses committed by its officials against migrants, for failing to provide access to humanitarian visas or asylum to migrants who have valid claims to international protection, and for detaining migrant children. |60|

The State Department has provided $15 million in equipment and training assistance, including NII equipment, mobile kiosks, canine teams, and training for INAMI officials in the southern border region. It plans to spend at least $75 million in that area. The Department of Defense has provided training and equipment to Mexican military forces as well. Observers have urged U.S. policymakers to consider providing Mexico with support in how to investigate and punish crimes against migrants, training in how to conduct humanitarian screening, and support for Mexico's asylum agency. |61|

Pillar Four: Building Strong and Resilient Communities

This pillar focuses on addressing the underlying causes of crime and violence, promoting security and social development, and building communities that can withstand the pressures of crime and violence. Pillar four is unique in that it has involved Mexican and U.S. federal officials working together to design and implement community-based programs in high-crime areas. Pillar four seeks to empower local leaders, civil society representatives, and private sector actors to lead crime prevention efforts in their communities. It has been informed by lessons learned from U.S. and Mexican efforts in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua.

Ciudad Juárez: Lessons Learned In January 2010, in response to the massacre of 15 youths with no connection to organized crime in Ciudad Juárez, the Mexican government began to prioritize crime prevention and community engagement. Federal officials worked with local authorities and civic leaders to establish six task forces to plan and oversee a strategy for reducing criminality, tackling social problems, and improving citizen-government relations. The strategy, "Todos Somos Juarez" ("We Are All Juárez"), was launched in February 2010 and involved close to $400 million in federal investments in the city. While federal officials began by amplifying access to existing social programs and building infrastructure projects, they later responded to local demands to concentrate efforts in certain "safe zones." Control over public security in the city shifted from the military, to the federal police, and then to municipal authorities. |62|

Prior to the endorsement of a formal pillar four strategy, the U.S. government's pillar four efforts in Ciudad Juárez involved the expansion of existing initiatives, such as school-based "culture of lawfulness" |63| programs and drug demand reduction and treatment services. Culture-of-lawfulness (CoL) programs aim to combine "top-down" and "bottom-up" approaches to educate all sectors of society on the importance of upholding the rule of law. U.S. support also included new programs, such as support for an anonymous tip line for the police. USAID supported a crime and violence mapping project that enabled Ciudad Juarez's government to identify hot spots and respond with tailored prevention measures as well as a program to provide safe spaces, activities, and job training programs for at-risk youth. USAID also provided $ 1 million in grants to local organizations working in the areas of social cohesion.

It may never be determined what role the aforementioned efforts played in the significant reductions in violence that has occurred in Ciudad Juárez since 2011. |64| Nevertheless, lessons have been gleaned from this example of Mexican and U.S. involvement in municipal crime prevention that are informing newer programs in Mexico and in Central America. Analysts have praised the sustained, high-level support Ciudad Juárez received from the Mexican and U.S. governments; community and private sector ownership of the effort; and coordination that occurred between various levels of the Mexican government. |65| The strategy was not well targeted, however, and monitoring and evaluation of its effectiveness has been relatively weak.

In April 2011, the U.S. and Mexican governments formally approved a binational pillar four strategy focused on (1) strengthening federal civic planning capacity to prevent and reduce crime; (2) bolstering the capacity of state and local governments to implement crime prevention and reduction activities; and (3) increasing engagement with at-risk youth. U.S.-funded pillar four activities were designed to complement the work of Mexico's National Center for Crime Prevention and Citizen Participation, an entity (since renamed) within the Interior Department that implements prevention projects. U.S. support for pillar four has exceeded $100 million.

USAID has dedicated $50 million for a crime and violence prevention program in nine target communities identified by the Mexican government in Ciudad Juárez, Monterrey, Nuevo León, and Tijuana, Baja California. The program has supported the development of community strategies to reduce crime and violence in the target localities, including outreach to at-risk youth, improved citizen-police collaboration, and partnerships between public and private sector entities. It included funding for an evaluation of crime in the target communities that will help enable both governments to identify successful models for replication. USAID also awarded local grants to civil society organizations for innovative crime prevention projects that engage at-risk youth.

Initially, pillar four appeared to be a top priority for the Peña Nieto government, but recent funding and leadership challenges (mentioned above) could hinder the results of Mexico's National Crime and Violence Prevention Program. |66| As previously stated, that program involves federal interventions in municipalities in high crime areas.

The State Department is supporting other key elements of pillar four: drug demand reduction, culture of lawfulness programs, and efforts to help citizens hold government entities accountable. U.S.-funded training and technical assistance provided by the Inter-American Drug Control Commission has helped Mexico develop a curriculum and train hundreds of drug counselors, conduct research, and expand drug treatment courts throughout the country. U.S. support has also enabled the establishment of community anti-drug coalitions in Mexico. As Mexico has made culture of lawfulness education a required part of middle school curriculum, U.S. support has helped that curriculum reach more than 800,000 students during the 2013-2014 school year. |67| U.S. assistance has helped a Mexican nongovernment organization establish citizens' watch booths in district attorney's offices in Mexico City and surrounding areas that have helped people report crime, be made aware of their rights, and monitor the services provided by those entities.

Issues

Measuring the Success of the Mérida Initiative

With little publicly available information on what specific metrics the U.S. and Mexican governments are using to measure the impact of the Mérida Initiative, analysts have debated how bilateral efforts should be evaluated. How one evaluates the Mérida Initiative largely depends on how one has defined the goals of the program. While the U.S. and Mexican governments' long-term goals for the Mérida Initiative may be similar, their short-term goals and priorities may be different. For example, both countries may strive to ultimately reduce the overarching threat posed by the DTOs—a national security threat to Mexico and an organized crime threat to the United States. However, their short-term goals may differ; Mexico may focus more on reducing drug trafficking-related crime and violence, while the United States may place more emphasis on aggressively capturing DTO leaders and seizing illicit drugs.

For years, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has urged U.S. agencies working in Mexico to adopt outcome-based measures, not just output measures. |68| For example, rather than calculating the number of police trained, the GAO would urge the creation of a measure to see how U.S. training affected police performance. The State Department worked internally, with external contractors, and with two different Mexican governments to try to develop a set of indicators that could measure the efficacy of Mérida Initiative programming without overstating the impact—positive or negative—of U.S. programs. In September 2015, a contractor submitted a final report to the U.S. and Mexican governments containing more than 200 suggested indicators to evaluate the Mérida Initiative. It has yet to be made public, but reportedly contains a mix of indicators that include output, outcome, and crime perception variables. |69|

Extraditions

Another example of Mérida success—in the form of bilateral cooperation—cited by the State Department is the high number of extraditions from Mexico to the United States.

Figure 2. Individuals Extradited from Mexico to the United States

1995-2014

Sources: U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Department of State.

Extraditions to the United States had started to increase under former President Vicente Fox (2000-2006), who like Felipe Calderón was from the opposition PAN, and reached 63 in 2006. Starting at 83 in 2007, in the six full years of the Calderón Administration, extraditions rose to nearly 100 a year. Cooperation on extraditions peaked in 2012, the final year of the Calderón government, with 115 favorable responses to U.S. extradition requests.

In 2013, the number of extraditions declined to 54. Given the transition to a new administration in Mexico, there are several possible reasons for that decline. According to Mexican officials, extradition requests from the United States to Mexico declined from 108 in 2012 to 88 in 2013. Moreover, the Calderón government did not leave a large backlog of cases waiting to be processed in 2013. |70| In 2014, extraditions from Mexico rose to 66.

Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán's escape appears to have changed the Mexican government's position on extraditions. Previously, the Mexican government had maintained that it was unlikely to grant any U.S. extradition request for Guzmán (where he faces multiple charges) until he had served his time in Mexico. Possibly due to Mexican opposition, the U.S. Department of Justice reportedly did not submit a formal extradition request for Guzmán until June 2015. |71| Mexico extradited 13 top drug traffickers to the United States in September 2015 and quickly initiated procedures to extradite Guzmán following his January 8 capture. The process could reportedly take from several months to a year or more, however, due to injunctions and other delaying tactics that are likely to be used by Guzmán's defense attorneys. |72|

Drug Production and Interdiction in Mexico

Drug eradication and alternative development programs have not been a focus of the Mérida Initiative even though Mexico is a major producer of opium poppy (used to produce heroin), methamphetamine, and cannabis (marijuana). According to U.S. government estimates, opium production has surged in Mexico |73| as cannabis production has fallen. In addition, despite Mexican government import restrictions on precursor chemicals and efforts to seize precursor chemicals and dismantle clandestine labs, the production of methamphetamine, which has an average purity of some 96%, has continued at high levels. |74|

The Mexican government has engaged its military in drug crop eradication efforts since the 1930s, but personnel constraints have inhibited recent eradication efforts. Because of the terrain where drug crops are grown and the small plot sizes involved, Mexican eradication efforts have predominantly been conducted manually. Increases in drug production have occurred as the government has assigned more military forces to public security functions, including anti-DTO operations, than to drug crop eradication efforts. However, the Mexican government significantly increased its eradication of poppy and slightly increased its eradication of marijuana in 2014 over 2013, according to the 2015 INCSR. The State Department is in discussions with the Mexican government on ways in which cooperation on combating the production and trafficking of heroin can be augmented, including the possibility of increasing opium poppy eradication.

The Mexican government has not traditionally provided support for alternative development, even though many drug-producing regions of the country are impoverished rural areas where few licit employment opportunities exist. Alternative development programs have traditionally sought to provide positive incentives for farmers to abandon drug crop cultivation in lieu of farming other crops, but may be designed more broadly to assist any individuals who collaborated with DTOs out of economic necessity to adopt alternative means of employment. In Colombia, studies have found that the combination of jointly implemented eradication, alternative development, and interdiction is more effective than the independent application of any one of these three strategies. |75| Despite those findings, alternative development often takes years to show results and requires a long-term commitment to promoting rural development.

While Mexico has made arresting drug kingpins a top priority, it has not given equal attention to the need to increase drug seizures. The State Department's International Narcotics Control Strategy Reports covering 2013 |76| asserted that less than 2% of the cocaine estimated to transit Mexico is seized by Mexican authorities. The State Department has provided canines and inspection equipment for interdiction at Mexico's borders and ports of entry that has helped increase seizures, yet cocaine seizures in Central American countries often exceed Mexico's cocaine interdiction figures. The State Department reports that Mexico's seizures of methamphetamine jumped by almost 36% between 2013 and 2014 to 19.8 metric tons, and Mexican authorities seized 143 meth laboratories in 2014, up more than 11% from 2013. |77| The Mexican marines have taken over control of the country's ports and have been actively interdicting precursor chemicals arriving from Asia and elsewhere. According to Mexico's Attorney General's office, Mexico seized 40% less cocaine in 2014 than the year before, but increased its seizures of opium gum by 400%. |78|

Human Rights Concerns and Conditions on Mérida Initiative Funding

There have been ongoing concerns about the human rights records of Mexico's military and police, particularly given the aforementioned cases (Tlatlaya, Iguala) involving allegations of their involvement in torture, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings. The State Department's annual human rights reports covering Mexico have cited credible reports of police involvement in extrajudicial killings, kidnappings for ransom, and torture. |79| There has also been concern that the Mexican military has committed more human rights abuses since being tasked with carrying out public security functions.

In addition to expressing concerns about current abuses, Mexican and international human rights groups have criticized the Mexican government for failing to hold military and police officials accountable for past abuses. In May 2014, Mexico revised the country's military justice code to comply with rulings by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and decisions by Mexico's Supreme Court affirming that cases of military abuses against civilians should be tried in civilian courts. In the past year, civilian courts, some operating with oral trials, have begun to hold military officials accountable for past abuses. In August 2015, an Army lieutenant became the first Mexican military official charged with enforced disappearance. |80|

Congress has expressed ongoing concerns about human rights conditions in Mexico. These concerns have intensified as U.S. security assistance to Mexico has increased under the Mérida Initiative. Congress has continued monitoring adherence to the "Leahy" vetting requirements that must be met under the Foreign Assistance Act (FAA) of 1961 as amended (22 U.S.C. 2378d) |81| and annual Department of Defense (DOD) appropriations |82| in order for Mexican security forces |83| to receive U.S. support. |84|

Since FY2008, Congress has also conditioned U.S. assistance to the Mexican military and police on compliance with certain human rights standards. In an October 19, 2015, briefing, a spokesperson said that although the State Department was "unable to confirm and report to Congress that Mexico fully met all of the [human rights] criteria in the Fiscal Year 2014 appropriation legislation (P.L. 113-76)... [it continues] to strongly support Mexico's ongoing efforts to reform its law enforcement and justice systems." As a result of the State Department's decision not to submit a report for Mexico, some $5 million in International Narcotics and Law Enforcement assistance (INCLE) was reprogrammed to Peru. Mexico lost close to $500,000 in Foreign Military Financing (FMF) that was withheld as well. Mexican officials publicly rejected the State Department's decision, but it has reportedly not hindered bilateral efforts. |85|

The FY2015 Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act (P.L. 113-235) requires that 15% of certain International Narcotics and Law Enforcement and Foreign Military Financing assistance be withheld until the Secretary of State reports in writing that:

1. the government of Mexico is investigating and prosecuting violations of human rights in civilian courts;

2. the government of Mexico is enforcing prohibitions against torture and the use of testimony obtained through torture;

3. the Mexican army and police are promptly transferring detainees to the custody of civilian judicial authorities, in accordance with Mexican law, and are cooperating with such authorities in such cases; and,

4. the government of Mexico is searching for the victims of forced disappearances and is investigating and prosecuting those responsible for such crimes.

There were no withholding requirements in the House Appropriations Committee-passed version of the FY2016 Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs appropriations bill (H.R. 2772). The report (S. Rept. 114-79) accompanying the Senate Appropriations Committee-passed version of the FY2016 Foreign Operations bill (S. 1725) contains the restrictions ultimately included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, FY2016 (P.L. 114-113). They are similar to those described above in P.L. 113-235, but apply to the $5 million in Foreign Military Financing (FMF) rather than to Mérida Initiative aid. |86|

Human rights groups initially expressed satisfaction that President Peña Nieto had adopted a pro-human rights discourse and promulgated a law requiring state support for crime victims and their families. If in 2013 they were underwhelmed with his government's efforts to promote and protect human rights, they have vigorously criticized the government's handling of high-profile cases of alleged abuses in 2014 and the lack of protection it has provided for groups vulnerable to abuses (journalists, human rights defenders, migrants). |87| They supported the State Department's decision not to submit an FY2014 human rights progress report for Mexico. |88|

The State Department has established a high-level human rights dialogue with Mexico, provided human rights training for Mexican security forces, and implemented a number of human rights-related programs. USAID has supported a $5 million program being implemented by Freedom House to improve protections for Mexican journalists and human rights defenders that is in the process of being extended and augmented. USAID is dedicating $25 million through 2018 for that and other human rights programs focused on helping Mexico develop a national human rights strategy, assist victims of torture and other abuses, and develop and implement legislation related to preventing and punishing human rights abuses.

Congress may choose to augment Mérida Initiative funding for human rights programs, such as ongoing training programs for military and police, or newer efforts, such as support for human rights organizations. Human rights conditions in Mexico, as well as compliance with conditions on Mérida assistance, are also likely to continue to be important oversight issues. As funds are provided to help secure Mexico's southern border, Congress may additionally consider how to help mitigate concerns about migrants' rights in Mexico.

Role of the U.S. Department of Defense in Mexico

In contrast to Plan Colombia, the Mérida Initiative does not include an active U.S. military presence in Mexico, largely due to Mexican concerns about national sovereignty stemming from past conflicts with the United States. The Department of Defense (DOD) did not play a primary role in designing the Mérida Initiative and is not providing assistance through Mérida accounts. However, DOD oversaw the procurement and delivery of equipment provided through the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) account, which was part of Mérida until FY2012.

Despite DOD's limited role in the Mérida Initiative, military cooperation between the two countries has been increasing, as have DOD training and equipment programs to support the Mexican military. |89| DOD has sent unmanned aerial vehicles into Mexico to gather intelligence on criminal organizations. DOD is also providing training and equipment to Mexican military forces patrolling the country's southern borders. More broadly, DOD assistance aims to support Mexico's efforts to improve security in high-crime areas, track and capture DTO operatives, strengthen border security, and disrupt illicit flows.

There are a variety of funding streams that support DOD training and equipment programs. Some DOD equipment programs are funded by annual State Department appropriations for FMF, which totaled $5 million in FY2015. For their part, International Military Education and Training (IMET) funds, which totaled $1.5 million in FY2015, support training programs for the Mexican military, including courses provided in the United States (see Appendix).

Apart from the Mérida Initiative and other State Department funding, DOD provides additional training, equipping and other support through its Drug Interdiction and Counterdrug Activities account that complements the Mérida Initiative. DOD funding is not subject to the same human rights withholding provisions as State Department appropriations, but individuals and units receiving DOD support are vetted for potential human rights issues in compliance with the Leahy Law. DOD programs in Mexico are overseen by U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM), which is located at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado. DOD support to Mexico totaled some $43.1 million in FY2014 and $43.9 million in FY2015.

The aforementioned counternarcotics funding has enabled NORTHCOM to train and equip an increasing number of Mexican military personnel. In FY2015, NORTHCOM trained 4,598 military personnel, up from 3,413 in FY2014. Training has included courses on information fusion, surveillance, interdiction, cybersecurity, logistics, and professional development. Equipping efforts provided non-lethal equipment (such as communications tools, aircraft modifications, night vision, boats, etc.) to support those training courses.

Policymakers may want to receive periodic briefings on DOD efforts in order to guarantee that DOD programs are being adequately coordinated with Mérida Initiative efforts, complying with U.S. vetting requirements, and not reinforcing the militarization of public security in Mexico.

Balancing Assistance to Mexico with Support for Southwest Border Initiatives

The Mérida Initiative was designed to complement domestic efforts to combat drug demand, drug trafficking, weapons smuggling, and money laundering. These domestic counter-drug initiatives are funded through regular and supplemental appropriations for a variety of U.S. domestic agencies. As the strategy underpinning the Mérida Initiative has expanded to include efforts to build a more modern border (pillar three) and to strengthen border communities (pillar four), policymakers may consider how best to balance the amount of funding provided to Mexico with support for related domestic initiatives.

Regarding support for law enforcement efforts, some would argue that there needs to be more federal support for states and localities on the U.S. side of the border that are dealing with crime and violence originating in Mexico. Of those who endorse that point of view, some are encouraged that the Obama Administration has increased manpower and technology along the border, whereas others maintain that the Administration's efforts have been insufficient to secure the border. |90| In contrast, some maintain that it is impossible to combat transnational criminal enterprises by solely focused on the U.S. side of the border, and that domestic programs must be accompanied by continued efforts to build the capacity of Mexican law enforcement officials. They maintain that if recent U.S. efforts are perceived as an attempt to "militarize" the border, they may damage U.S.-Mexican relations and hinder bilateral security cooperation efforts. Mexican officials from across the political spectrum have expressed concerns about the construction of border fencing and the effects of border enforcement on migrant deaths. |91|

With respect to pillar four of the updated strategy, as previously mentioned, Mexico and the United States have supported programs to strengthen communities in Ciudad Juarez, Monterrey, and Tijuana. In targeting those communities most affected by the violence, greater efforts will necessarily be placed on community-building in Ciudad Juarez and Tijuana than on their sister cities in the United States. However, if the U.S. government provides aid to these communities in Mexico, some may argue that there should also be federal support for the adjacent U.S. border cities. For example, initiatives aimed at providing youth with education, employment, and social outlets might reduce the allure of joining a DTO or local gang. Some may contend that increasing these services on the U.S. side of the border as well as the Mexican side could be beneficial.

Integrating Counterdrug Programs in the Western Hemisphere

U.S. State Department-funded counterdrug assistance programs in the Western Hemisphere are currently in transition. Counterdrug assistance to Colombia and the Andean region is in decline after record assistance levels that began with U.S. support for Plan Colombia in FY2000 and peaked in the mid-2000s. Anti-drug aid to Mexico increased dramatically in FY2008-FY2010 as a result of the Mérida Initiative, but has since been reduced as well. Conversely, funding for Central America has increased as a result of the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI). |92|

Support for the Caribbean increased in FY2010 and has remained relatively stable due to the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative (CBSI).