| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

22Dec14

Final report of the International Commission of Inquiry on the Central African Republic

Back to topUnited Nations

Security CouncilS/2014/928

Distr.: General

22 December 2014

English

Original: FrenchLetter dated 19 December 2014 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council

I have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the International Commission of Inquiry on the Central African Republic, received from the Chair of the Commission in accordance with Security Council resolution 2127 (2013) (see annex).

I should be grateful if you would bring the report to the attention of the members of the Security Council.

(Signed) BAN Ki-moon

Contents

I. Introduction and methodology

II. Historical Background and Political Context

III. The Importance of Addressing Impunity in the CAR

IV. The Applicable International Legal Framework

VI. The Road to Accountability

A. The CAR Legal System

B. The Special Criminal Court

C. The Sanctions Committee and the Panel of Experts

D. The International Criminal Court

E. Drawing ConclusionsVII. Conclusions and Recommendations

A. Conclusions

B. Recommendations

1. To the National Transitional Government of the CAR

2. To the National Transitional Government of the CAR and the MINUSCA

3. To MINUSCA

4. To the Security Council

5. To the Secretary-General of the United Nations

6. To the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

7. To the United Nations Human Rights Council

8. To the Regional Organisations (AU, EU, ECCAS and OIF)Annex A:

The Applicable International Legal FrameworkAnnex B:

Violations and Abuses of International Human Rights Law and International Humanitarian LawI. The Armed Forces (FACA) and the Presidential Guard

II. The Séléka

III. The Anti-balaka

IV. Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

V. Cross-Cutting IssuesAnnex I: Zones of Influence of Séléka and anti-balaka

Annex II: Ethnic groups in the CAR

Annex III: Total IDPs, refugees and evacuees since December 2013, as of 31 March 2014

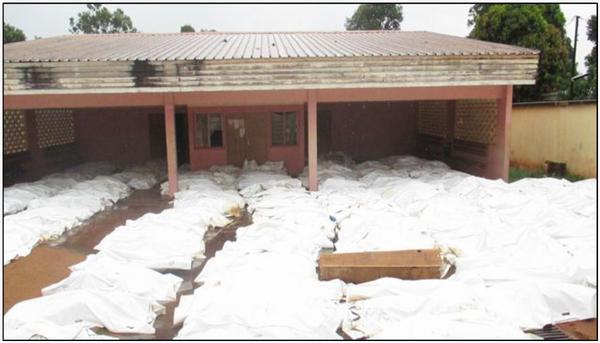

Annex IV: Pictures taken at the morgue in Bangui in the days following the 5 December 2013 attack

ACHPR African Charter on Human and People's Rights BINUCA Integrated United Nations Peace-building Office in the CAR CAR Central African Republic CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women COCORA Coalition citoyenne d'opposition aux rebellions armées CPJP Convention des patriotes pour la justice et la paix ECCAS Economic Community of Central African States EUFOR European Force in the CAR FACA Forces Armées Centrafricaines FAO Food and Agricultural Organisation FDPC Front Démocratique du Peuple Centrafricain FIDH Fédération internationale des droits de l'homme FOMAC Force Multinationale de l'Afrique centrale ICC International Criminal Court ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ICESCR International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross ICTR International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda ICTY International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia IDP Internally Displaced Person IOM International Organization for Migration MISCA African-led International support mission in the Central African Republic MINUSCA United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the CAR OCHA Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs of the United Nations OHCHR Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights UDHR Universal Declaration of Human Rights UFDR Union des Forces Démocratiques pour le Rassemblement UFR Union of Republican Forces UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

Annex-

[Original: English]

United Nations Nations Unies La Commission d'enquête internationale sur

la République CentrafricaineThe International Commission of Inquiry on

the Central African RepublicFINAL REPORT

Pursuant to Security Council resolution 2127 of 5 December 2013 which established an International Commission of Inquiry to investigate international human rights and humanitarian laws violation and abuses in CAR by all the parties involved in the armed conflict since 1 January 2013. The Secretary-General of the United Nations appointed Madame Fatimata M'Baye, Professor Philip Alston and Bernard A Muna as members of the Commission. Bernard A. Muna was asked by the Secretary-General to Chair the Commission.

In paragraph 24 of resolution 2127, the Security Council requested the Commission to compile information to help identify the perpetrators of such violations and abuses, point to their possible criminal responsibility and help ensure that those responsible are held accountable.

The Commission started work only in April 2014, under very difficult conditions, including a hostile and violent atmosphere that made it difficult for investigators to carry out their work, especially in the interior of the country. It was initially able to conduct investigations, albeit only in a constrained and limited manner, of the violations and abuses that were committed in Bangui, parts of which enjoyed relative calm at certain intervals, thus permitting access by investigators.

Working under these conditions, the Commission nevertheless filed a preliminary report, after only two months of limited investigations, in June 2014, in keeping with paragraph 25 of resolution 2127.

This second report is a result of investigations largely carried out on violations and abuses that took place in Bangui and the western part of the country. The investigators visited 15 towns and surrounding villages outside Bangui to meet with victims, their relatives, witnesses and alleged perpetrators.

At the onset of its activities, the Commission drew up an ambitious but realistic plan to undertake a far wider range of investigative missions, covering the key areas most affected by the violence in the western part of the country. However missions to the central part of the CAR proved impossible due to high security risks to the members of the investigating teams.

The Commission gathered as much information as possible and attached great importance to meeting with the President and members of the National Transitional Government, members of the diplomatic community in Bangui, United Nations organs and agencies, and international and national NGO's. The Commission also met with members of the CAR judicial and prosecution services, private legal practitioners as well as leaders of their respective associations.

In keeping with the letter and spirit of the Security Council resolution, the Commission made it a duty to investigate all violations and abuses of human rights and humanitarian laws. However since there were a large range of abuses committed over the period covered by the mandate, the Commission has had to focus most of its efforts on the more serious abuses.

The Commission carried out 910 interviews with victims, witnesses, family members and other relevant individuals in CAR as well as those who fled to Cameroon.

The Commission has, throughout its work, always kept in mind the fact that the one thing that the Security Council particularly wished to put an end to the reigning climate of impunity in CAR. This impunity has been a major factor in fuelling the present armed conflict, in large part because similar conflicts in the past have never been followed by measures designed to hold to account the major players responsible for crimes and violations committed. On the contrary, the major players have usually stage-managed a "national reconciliation" and seen to it that self-serving amnesty laws were enacted to cover themselves from any prosecutions. The holding of perpetrators of violations and abuses of human rights and humanitarian law accountable for their acts will make an important contribution to putting an end to impunity in CAR.

The Commission is satisfied at this stage of the investigations, that a non-international armed conflict took place in CAR, during different parts of the period covered by the mandate of the Commission that is, from 1 January, 2013 to 24 March 2013, when President Bozizé left power and after 4 December 2013 to the present. It is the view of the Commission that from 24 March when Djotodia took over as President of a Transitional government until he resigned on the 5 December 2013, there were internal disturbances or violence but the Commission did not consider they reached the level of non- international armed conflict.

The Commission is further satisfied that the parties to this conflict are: the members of the Armed Forces of the CAR (FACA) under President Bozizé (FACA), and the principal militia groups, the Séléka and the anti-balaka. The Commission is satisfied that the investigations it has conducted have established that all the parties were involved in serious violations of international humanitarian law and gross abuses of human rights including rape and other gender based sexual offences and violations. Many of these abuses are also characterized by the Commission as having amounted to crimes under both domestic law and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

The Commission also investigated allegations against the UN and other international peace keeping forces, which were brought to its attention. While appreciating the difficulties that such forces face in carrying out their duties and obligations under the prevailing conditions in CAR, the Commission believes that a more systematic and institutionalized response is needed to deal with such allegations in the future. Accordingly, several recommendations are made to address this challenge.

The Commission is aware that its establishment was brought about as a response to the horrendous abuses of human rights and humanitarian law, and the fear that the conflict in CAR could quite easily turn to a genocidal killing spree. However after examining all the available evidence, the Commission concludes that the threshold requirement to prove the existence of the necessary element of genocidal intent has not been established in relation to any of the actors in the conflict. It emphasizes, however, that this does not in any way diminish the seriousness of crimes that have been committed and documented in its report. Nor does it give any reason to assume that in the future the risk of grave crimes, including genocide, will inevitably be averted. In this regard it must be accepted that timely action taken by the African Union and French peace keeping forces as well as BINUCA-MINUSCA, and the Security Council resolution 2127 have been primarily responsible for the prevention of an even greater explosion of violence.

The Commission considers that in the context of the CAR conflict, it is not in a position to establish with any degree of accuracy the number of people who were killed in the conflict, during the two years covered by the mandate. The difficulties of collecting accurate data in this regard are due to various reasons, including the practice of Muslim communities to bury their dead almost immediately and the difficulty of getting access to mass graves, especially in the countryside and forests, in the midst of continuing conflicts. The various estimates so far available during this period range from 3,000 to 6,000 people killed, but the Commission considers that such estimates fail to capture the full magnitude of the killings that occurred.

The report of the Commission ends with recommendations made to the National Transitional Government of the CAR, MINUSCA, the Security Council, the Secretary-General, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the United Nations Human Rights Council, and the relevant regional Organizations (AU, EU, ECCAS and OIF).

I Introduction and methodology

1. This second and final report of the Commission of Inquiry is submitted pursuant to paragraph 25 of Security Council resolution 2127 of 5 December 2013 by which the Council requested the Secretary-General to report to it on the findings of the Commission one year after the adoption of the resolution.

2. The Commission's mandate is contained in paragraph 24 of Security Council resolution 2127 (201(3). Acting under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations, the Council requested the Secretary-General to rapidly establish an International Commission of Inquiry to investigate reports of violations of international humanitarian law, international human rights law and abuses of human rights in the Central African Republic (CAR), by all parties since 1 January 2013, compile information, help identify the perpetrators of such violations and abuses, point to their possible criminal responsibility, and help ensure that those responsible are held accountable. The Council also called on all parties to cooperate fully with the Commission.

3. On 22 January 2014 the Secretary-General appointed three high-level experts as members of the International Commission of Inquiry for the Central African Republic: Jorge Castaneda (Mexico), Fatimata M'Baye (Mauritani(a) and Bernard Acho Muna (Cameroon). Mr Muna was appointed Chair of the Commission. In March 2013 Mr. Castaneda resigned, for personal reasons. On 18 August 2014 the Secretary-General appointed Philip Alston (Australi(a) as a member of the Commission.

4. The Council has mandated the Commission to consider reports of violations of international humanitarian law, international human rights law and abuses of human rights. In addition, international criminal law is a central frame of reference for this report. This reflects the fact that the CAR ratified the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (IC(C) on 3 October 2001, thereby giving the Court jurisdiction over relevant crimes committed on the territory of the CAR or by its nationals since 1 July 2002. On 30 May 2014 the transitional government of the CAR referred the situation on the territory of the CAR since 1 August 2012 to the Prosecutor of the ICC, and on 24 September 2014 the Prosecutor of the Court indicated that she had determined that there is a reasonable basis, in accordance with Article 53 of the Rome Statute, to proceed with an investigation. That investigation is now underway.

5. The Secretariat of the Commission was based in Bangui, CAR. For the adoption of this second and final report, however, the three Commissioners and the Secretariat convened in November 2014 in Yaounde because of the prevailing insecurity in CAR. The Commission is grateful to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and its Central African Regional Office for having provided the Secretariat, but wishes to underscore its independence from the Office as well as all other actors relevant to this situation.

6. The Commission's mandate limits its temporal focus to events that occurred on or after 1 January 2013, although this report takes note of earlier events where appropriate to an understanding of the situation during the period under review. The information contained in this report is current up to 1 November 2014.

7. At the outset of its activities, the Commission drew up an ambitious but realistic plan to undertake a range of investigative missions covering the key areas most affected by the violence, in the western part of the CAR. But following the shift of the conflict to the central part of the country, mainly to the Ouaka province, missions to that area proved not to be feasible due to the highly problematic security situation. Nevertheless, the Commission has received at least some information from various sources relating to violations and abuses that are alleged to have occurred in that area and these have been recorded in its database and taken into account in its report. The Commission recognizes, however, that future efforts will need to give particular attention to recording and following up on violations and abuses in the central part of the CAR but also to the east, where violence was also reported.

8. Therefore, the Commission's fact-finding activities were largely focused on events that occurred in the western part of the country. In that regard, missions of investigation were undertaken to Boali, Mbaiki, Boda, Bossembélé, Yaloké, Gaga, Bekadili, Bossemptélé, Bozoum, Ngoutere, Bocaranga, Bohong, Bouar, Baoro and Tattale, Bossangoa and Zere. In addition to collecting information within the territory of the CAR, the Commission's investigators conducted missions to both Cameroon and Chad, particularly in order to be able to interview victims and witnesses who had fled from the violence and sought refuge in these neighbouring countries. The mission to Cameroon was very successful. Unfortunately, the mission to Chad, which commenced on 4 November 2014, was unable to undertake its work. While the investigative team received a visa to travel to Chad, its requests in Ndjamena to obtain the necessary authorization to visit the refugee camps were not approved.

9. In terms of material coverage, the Commission was mandated to investigate all abuses of human rights and humanitarian law, without any restriction as to their gravity or seriousness. But the Council also emphasized the task of identifying perpetrators, exploring criminal responsibility, and ensuring accountability. Given the large range of abuses committed over a period of almost two years, the Commission has unavoidably focused most of its efforts on the more serious violations, and especially those for which it is reasonable to expect that accountability might be exacted in the future.

10. In gathering information, the Commission has endeavoured to cast as wide a net as possible. It has met with many senior government officials, including the President of the National Transitional Government, the former and current Prime Ministers, the former and current Ministers of Justice and Defence, and the Ministers of Foreign Affairs, Health, Social Affairs and Education. It also spoke with senior members of the judiciary and prosecution service, and reviewed case files and other dossiers they provided.

11. The Commission's investigators have conducted some 910 interviews with victims, witnesses, family members, alleged perpetrators and other relevant individuals in the Central African Republic, as well as with those who have fled to Cameroon. Where possible these inquiries have involved on-site visits to locations in which the relevant incidents occurred. The Commission has also met with a large number of community and religious groups and their representatives, the Bar Association and the Association of Magistrates, and with the leaders of different political parties and factions, as well as armed groups. These meetings have enabled it to take account of as many perspectives as possible and to corroborate or cast doubt on information collected from other sources.

12. The Commission and its investigators have also met with local and international non-governmental organizations, especially those that have been able to provide first-hand and other accounts of the events under review. It has thus been able to draw on the information provided in the detailed reporting of these diverse groups, while at the same time exercising its own judgment, based on all available sources, as to which accounts can be considered reliable and which would require further corroboration before being accepted.

13. The Commission met with the Special Representative of the Secretary-General and other senior officials of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSC(A), representatives of the African Union and of MISCA, and representatives of Operation Sangaris, as well as with interlocutors from the diplomatic community, and various international agencies.

14. The results of these wide-ranging consultations have been carefully recorded in an extensive database compiled by the Commission which seeks to track and document all known incidents involving alleged human rights or humanitarian law abuses, based on its own inquiries and interviews, open-source documents, material shared with it in confidence, and other appropriate material that it considers to be generally reliable.

15. The Commission has operated on the basis that the information provided to it must be assumed to be confidential, unless otherwise agreed by the relevant source. It is committed to protecting the particulars, the privacy and the security of information provided by those victims, witnesses and other sources who requested that their identity and particulars not be disclosed. Those requesting confidentiality are in a minority among the Commission's sources, but even the information provided on that condition has proven to be very useful both to inform the overall analysis and to furnish carefully anonymized examples of abuses.

16. The standard of proof applied by the Commission in its work is that there are "reasonable grounds to believe" that a particular incident occurred or that a given pattern of violations prevailed. The Commission has endeavoured to apply this standard with an appropriate degree of rigor, although the feasibility of different techniques of verification, cross-checking, and corroboration inevitably differs according to the context involved. This approach is fully consistent with that commonly used in international fact-finding inquiries of this sort. |1| In seeking to identify individual perpetrators, the same standard has been applied. This means that it does not rise to the level of proof beyond reasonable doubt that would be required to establish individual criminal responsibility in a court of law. This is because the Commission is neither a prosecutor nor a court. Instead, its task in relation to alleged perpetrators is to marshal a reliable body of information, that is consistent with and supported by as many sources as possible, in order to provide the foundations for a full-fledged criminal investigation to be undertaken in the future by the appropriate national and/or international authorities.

17. The rigorous application of this standard of proof has meant, for example, that the Commission has not been able to make full use of some of the photographic and video materials to which it has been given access, because it has not been able to authenticate or situate the materials in accordance with the required standard.

18. Despite the breadth of its mandate and the large amount of information collected, the Commission has sought to limit the length of its report in line with United Nations resolutions on the control of documentation and word limits.

19. The Commission expresses its gratitude to a large number of individuals and institutional actors who have cooperated with it to enable it to carry out its work. In addition to the Government of the National Transitional Authority, and the Government of Cameroon, the Commission has benefited greatly from the assistance of MINUSCA and its predecessors, and especially from the support of the Head of MINUSCA and Special Representative of the Secretary-General, Babacar Gaye. Various UN agencies, including UNICEF, UNHCR and UNHAS, have provided assistance, and UN Women which provided experts to work on issues relating to sexual and gender-based violence. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights also provided important support for the work of the Commission. The Office of the Prosecutor of the international Criminal Court facilitated access to its open-source material. In addition, a great many community groups, civil society actors, and non-governmental groups provided very valuable information and insights into the situation.

D. Challenges Faced by the Commission

20. The Commission faced significant challenges in carrying out its mandate. Being based in the CAR while the conflict was still on-going made the logistics especially complicated. Some of the parties to the conflict operated more like armed gangs, without any clear line of command, and violence could break out sporadically in any area, not only between the parties to the conflict but from time to time between the members of the same group.

21. Over the past year, there has been a consistent deterioration in the security situation in the CAR, sometimes resulting in the imposition of restrictions on the movements of the investigators and other staff. Anti-balaka militias also targeted Muslims of all nationalities, even if they were United Nations staff members. On 9 June 2014, on their way to Boali, eight members of the Commission's investigation team |2| (including drivers and interpreters) were taken hostage for six hours during their first mission outside Bangui and faced death threats from the anti-bakala. On 12 October, seven members of the Commission including three WHO staff members and five members of the IRC were stranded in Boali because of the deterioration in the security situation. They were obliged to abandon their vehicles at the MINUSCA compound in Boali and return to Bangui in armoured vehicles. On two occasions, Muslim investigators working for the Commission were directly targeted by the anti-bakala. In some cases, they were forced to change their names when out on mission to gather information.

22. This final report on the work of the Commission responds to each of the different elements contained in the mandate provided by the Security Council. It thus undertakes a detailed and systematic review of the relevant abuses and violations that are reported to have taken place between 1 January 2013 and 1 April 2014. For reasons described above, the Commission could not conduct investigations in the central part of the Country, where focus of the conflict has shifted since May 2014. By definition, such a review cannot be comprehensive and the omission of unreported abuses should not be interpreted as diminishing their importance or of downplaying the need for those responsible to be held to account.

23. The report provides a detailed explanation of the applicable legal framework, it emphasizes the central importance of tackling impunity in the CAR, and it examines questions of criminal responsibility for the most significant abuses. It concludes with recommendations designed to enable the Security Council and Member States to assist the Government and the people of the CAR to ensure accountability for the past and to build meaningful and enduring institutions capable of helping to prevent recurrences of such events and of investigating, prosecuting and punishing those responsible for future abuses.

24. The Commission is not a judicial body but it views its work as a vital step towards encouraging and facilitating criminal investigations and prosecutions to be undertaken in order, as the Security Council's resolution put it, to "help ensure that those responsible are held accountable. " In compliance with resolution 2127, the Commission has drawn up an annex which consists of the names of a significant number of individuals whom it has reason to believe should be the subject of criminal investigations, along with a statement of the crimes of which each is suspected, and an outline of the evidence against them that has been obtained by the Commission. This annex, along with accompanying evidence and other relevant materials, will remain confidential and will be submitted to the Secretary General of the United Nations.

II. Historical Background and Political Context

25. In order to understand the current situation in the Central African Republic, it is necessary to take a brief look at the political evolution of this nation since it gained independence from France in 1960. The Central African Republic, a former colony of France, gained independence in 1960. During more than half a century of independence, the country has been ruled by military dictators for all but nine years. In the wake of these violent changes, corruption, the non-respect of human rights, repression of free political expression and nepotism, became institutionalized and endemic. The only goal of successive corrupt governments was personal enrichment of the political leaders and members of their families through embezzlement of public funds, looting of public corporations, and illegal exploitation of precious minerals and other natural resources while a very large majority of the people lived in abject poverty.

26. When Michel Djotodia Am-Nondroko ousted President Bozizé and took power on 24 March 2013, many people and rejoiced because they believed this would bring an end to their suffering. But their joy was short-lived because the foreign fighters which Djotodia and the Séléka coalition brought from Chad and Sudan and their local collaborators engaged in widespread violations and provoked sustained inter-ethnic, inter-tribal and inter-religious violence.

27. François Bozizé's ascent to power by means of a military coup in 2003, was strongly contested by civil society and the various political groups. This led to pressure from Economic Community of Central African States to organize transparent, free and fair democratic elections, although those that Bozizé held never met those conditions. In an attempt to work out a compromise and bring peace to CAR, ECCAS held many peace conferences mainly in Libreville between 2008 and 2011. Although these conferences produced agreements, none were ever implemented because of the intransigence of Bozizé. He was abandoned by his remaining supporters and Djotodia was allowed to take power and form a government of transition.

28. The wanton violence of the Séléka forces, especially after they had taken power, discredited the newly installed Djotodia regime. The anti-balaka militia, reinforced by elements of the disorganized and scattered FACA, organized themselves and carried out mass killings, looting and destruction of property under the pretext of retaliating for the violations against the non-Muslim and Christian communities by the Séléka forces. The latter responded with equal ferocity. The atrocities resulting from this explosion of violence, especially in Bangui, led ECCAS to compel Djotodia's resignation at a meeting in Ndjamena, on 10 January 2014.

29. After Djotodia's departure, the National Transitional Council was reconstituted and on 27 January 2014, a new National Transitional Government, headed by President Samba-Panza, was put in place. The transition is expected to be completed by August 2015, by which time the constitution will have been amended and local, legislative and Presidential elections organised.

III. The Importance of Addressing Impunity in the CAR

30. In the same resolution by which it established the present Commission, the Security Council expressly underlined the importance of bringing the perpetrators of violations of international humanitarian law, international human rights law and of human rights abuses in the CAR to justice. It also called upon the Transitional Authorities to investigate alleged abuses in order to hold perpetrators accountable. Progress in this direction, however, has been slow, at best. In his report to the Security Council in August 2014 the Secretary-General observed that "[s]erious and unabated violations of human rights and international humanitarian law are committed in a climate of total impunity." |3| And, more recently, the President of the Transitional Authority in a major address to the nation observed that while insecurity continued to be the main problem in the country, impunity was the second greatest problem. |4| The nature and extent of this problem has also been extensively documented in the reports of a wide range of civil society organizations. |5| And it is also a major focus of the present report.

31. Impunity has a long and tragic history in the CAR. As President Samba-Panza noted, both political and common law crimes committed on a massive scale against innocent persons have remained unpunished for at least the past two decades. But even before that time the record was not good. When Jean-Bédel Bokassa was forced from power in 1979 there was little to suggest that he would subsequently be held accountable for the many crimes he committed while he held the posts of President and Emperor. But in December 1986 he was put on trial and in June 1987 he was convicted of a range of crimes including murder. The very public nature of his trial and the fact that a former Head of State was sentenced to life imprisonment for his crimes, should have sent an important message. But no senior members of his government or the armed forces were tried for their part in the many crimes committed, and Bokassa himself was released from prison in 1993, as part of a general amnesty.

32. Since that time, as the High Commissioner for Human Rights has noted, the CAR has "experienced a number of mutinies, rebellions and coups d'état, along with gross violations of international human rights law and international humanitarian law," but "few of the suspected perpetrators have been prosecuted". |6| Instead, the norm has been the adoption of amnesty laws such as those of 30 May 1996, 15 March 1997 and 13 October 2008, which have given formal legitimacy to a longstanding situation of de facto impunity.

33. The last of these amnesty laws, for example, provided an amnesty from prosecution not only for all members of the defence and security forces, but also for the leaders and members of political-military groups operating within or outside the CAR, as from 15 March 2003. In addition, former President Patassé, his Defence Minister, and Martin Koumtamadji (subsequently known as Abdoulaye Miskin(e), along with their colleagues and accomplices were also given amnesty for the theft of public funds, killings, and complicity in killings. Exceptions were made, however, for acts amounting to war crimes, crimes against humanity, or other crimes over which the International Criminal Court has jurisdiction. Nevertheless, it was reported in 2009 that "impunity is pervasive for unlawful killings, regardless of the perpetrator (security forces, rebels, or private persons) or the context (military operations, routine law enforcement, or detention)." |7| Even after a major effort was made which resulted in 250 cases of human rights violations being referred to the judiciary and 80 convictions recorded in 2009, the bottom line was that senior members of the military and of the Government had, without exception, escaped judicial scrutiny. |8|

34. It is important to recall this historical record in order to avoid under-estimating the extent of the challenge that lies ahead. In a country that has seen persistent and vibrant impunity, the task of rebuilding and mobilizing a justice system that has almost never been able to hold powerful offenders to account will be a daunting one.

35. But in devising an approach to overcome impunity in the future it is essential to understand both the mentality and the assumptions that have driven it in the past. The consistent use of pardons to 'forgive' those accused of serious crimes has not only meant that those individuals have escaped accountability, but it has sent a strong and consistent message to wrongdoers that they need not worry about being punished in the future. Even if the justice system succeeds in prosecuting and convicting a handful of individuals, those convicted can confidently expect, on the basis of past experience, that they will soon be pardoned and be free to resume their predations.

36. This self-defeating dynamic has been regularly reproduced in the wake of each of the country's collapses from rampant corruption, the untrammeled exercise of both state and private power, and the abdication of proper governmental responsibilities. Each collapse is followed by an effort to put together a broad coalition of actors to help the country to recover, but the argument is always made that at least some of those responsible for egregious abuses will need to be included in the new coalition if it is to attract sufficient support from those who still wield power in the country in order to make it stick. Those individuals make it clear that they will repent of their old ways only if rewarded by appointment to a ministerial or other senior position in government. This strategy has been remarkably successful and is far from being absent today. The result is to provide a perverse incentive to wrongdoers to continue to behave badly in order to ensure that their participation in the new government will be considered indispensable to achieving a consensus outcome.

37. The Transitional Government, and indeed all domestic political actors, with the assistance of the international community, must work to break this cycle of impunity once and for all. The message needs to be sent that there can be no deals done in the future with those accused of serious crimes. There will always be suggestions that because the support of one individual or another is crucial in order to seal a deal, prosecutions should be abandoned or delayed or pardons issued. In the vast majority of cases, experience shows that such assessments will be greatly overstated, and no such deal should be made. In the handful of cases where this might not be the case, it becomes all the more imperative for the rule of law to prevail and for impunity to be rejected.

38. Thus a central goal of this report is to document the abuses and violations that have occurred and to begin the process of accountability by pointing to the criminal responsibility of perpetrators. As noted in section 6 below, the international community will need to play a crucial role if the necessary institutions are to be put in place and provided with the resources they need to begin to establish a new norm of accountability to replace the presumption of impunity, which continues to be alive and well in many respects.

IV. The Applicable International Legal Framework

A. Legal Classification of the Situation

39. International humanitarian law applies to the situation in the CAR at all times during which an armed conflict can be determined to exist under the applicable rules. These rules are complex and the pattern in the CAR during the period under review is a complicated one. The Commission has provided in Annex I below a full legal and factual analysis to justify the conclusions it has reached in this regard. In brief, the Commission has concluded that there was a non-international armed conflict taking place on the territory of the CAR from before 1 January 2013 and up until late March 2013, and again after 4 December 2013 until the present time. It thus applies the provisions of common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 in those contexts and, for the initial three-month period when the FACA was still functional, it also applies Additional Protocol II to the Geneva Conventions, relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts. For the remaining periods covered by this report, the Commission analyses the various alleged abuses only in terms of violations of international human rights law and crimes against humanity under the Rome Statute.

40. The Commission also concludes that a separate non-international armed conflict also existed for most if not all of the relevant time between the armed groups operating in the country and the French forces making up Operation Sangaris, who arrived in December 2013.

B. Bodies of Applicable International Law

41. The applicable law is also examined in detail in Annex I below. In brief, the Commission has applied three bodies of international law to the situation in the CAR. International human rights law, in the forms of both ratified treaties and customary norms, applied throughout the period covered by this report. In the context of an armed conflict, human rights law continues to be applicable, even if international humanitarian law might, under some circumstances, be considered to be the lex specialis. The Commission also adopts the widely accepted understanding that non-state groups that exercise de facto control over territory must respect human rights in their activities. As noted above, international humanitarian law also applies to those periods during which a non-international armed conflict existed. And international criminal law is applicable throughout the relevant period. It is also of particular relevance because the CAR ratified the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court on 3 October 2001. The Commission thus considers the extent to which genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes may have been committed.

V. Summary of Violations and Abuses of International Human Rights Law and International Humanitarian Law

42. Annex II of this report provides a detailed description and analysis of the violations and abuses committed by all of the principal actors during the almost two year period covered by this report. In many instances, these abuses rose to the level of international crimes. The description that follows is designed to give a brief overview of the Commission's detailed analysis of the relevant events.

43. Long before 1 January 2013, which is when the Commission's mandate begins, the CAR was involved in a non-international armed conflict between the government and the Séléka coalition. There was widespread repression of the government's political opponents and ordinary citizens, especially those of Muslim origin who were suspected of having close ties to the Séléka. Under the command of President Bozizé, the FACA and the Presidential Guard conducted extrajudicial killings and arbitrary arrests and illegally detained and tortured political opponents. In addition, the final months of the Bozizé Government saw a sudden surge in hate messages directed against the Muslim population.

44. The Séléka coalition, led by Michel Djotodia, took over Bangui on 23 March 2013 after a successful coup d'état. The coalition was mainly composed of fighters of Muslim faith, many of whom were from Chad or Sudan and did not speak Sango. Under the orders of the new government, they immediately sought to find and execute people loyal to the former regime, especially former politicians and FACA soldiers. Numerous rapes and widespread looting were reported in the neighborhoods of Bangui where the supporters of former President Bozizé lived. Similar violations occurred in many towns where the Séléka were present. Thousands of houses were also burnt or destroyed, and some churches were targeted. At the same time, the regime created the Comité extraordinaire de défense des acquis démocratiques (CEDAD) at whose base political opponents were illegally detained, tortured and killed.

45. Former president Francois Bozizé, former FACA soldiers, former gendarmes, politicians and others from Bozizé's inner circle met in Cameroon from June 2013 to plan a return to power. Most of them were Gbaya, Bozizé's ethnic group. Together they planned the attack on Bangui on 5 December 2013 and reached out to self-defense groups that were already present in the western part of the CAR, Bozizé's stronghold, to join the common purpose.

46. The first series of attacks by the anti-balaka were carried out in Bossangoa and surrounding areas in September 2013, resulting in dozens of civilian casualties. The Seleka retaliated by killing non-Muslims.

47. On December 5 2013, an attack was conducted by the anti balaka in Bangui. It deliberately targeted the Muslim population. The seleka was able to repel the attack, and thereafter went door-to-door killing hundreds of non-Muslim civilians suspected of being anti-balaka.

48. The next month witnessed a series of attacks by the anti-balaka and retaliatory attacks by the Séléka against the civilian population. Although Djotodia resigned on 10 January 2014, the anti-balaka continued to target the Muslim population, and the Séléka continued to kill non-Muslims.

49. The anti-balaka deliberately killed members of the Muslim population and on many occasions told the Muslims to go away and not come back. Their houses, as well as their mosques, were burned or destroyed. Muslims who tried to flee were frequently killed, whether in the towns, the bush, or in convoys that were taking them to refuge outside the country. Those Muslims who could not escape were forced to stay in enclaves under the protection of international forces. Surrounded by the anti-balaka, they were deliberately prevented from accessing food, water and medical care, thus reducing their living conditions to a deplorable state.

50. Thousands of people died as a result of the conflict. Human rights violations and abuses were committed by all parties. The Séléka coalition and the anti-balaka are also responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Although the Commission cannot conclude that there was genocide, ethnic cleansing of the Muslim population by the anti-balaka constitutes a crime against humanity.

VI. The Road to Accountability

51. The Commission has noted above the critical importance of putting an end to the impunity that has for so long characterized official responses to violations of human rights and international humanitarian law in the CAR. If accountability is to be achieved in the months and years ahead it will require concerted and complementary efforts by diverse actors. Several considerations should guide these efforts.

52. First and foremost is the concern to ensure that the perpetrators are systematically held to account, including in particular those responsible for the most serious violations.

53. Second, the prosecutions that take place must be, and be seen to be, fair and in compliance with international standards of justice.

54. Third, the system that is put in place for tackling past impunity must be capable of continuing to function as an effective and impartial deterrent to future violations. This means that the challenge should not be seen as a temporary one, and that the judicial institutions that will be called upon to try those accused of crimes over the almost two year period covered by the present report are supported in such a way as to build and strengthen their capacity to continue to uphold the rule of law in the CAR in the years ahead. This consideration will pose a particular challenge, given that a central part of the strategy that is currently being put in place is premised on the notion that the measures are urgent but also temporary, under the mandate provided by the Security Council for MINUSCA to adopt "urgent temporary measures." We return to this issue below.

55. In this section, the Commission considers: the current capacities of the judicial system in the CAR and the extent to which they can be expected to make an important contribution to putting an end to impunity; the role to be played by the Special Criminal Court that the authorities are in the process of establishing; the contribution of the Security Council's Sanctions Committee; and the role of the International Criminal Court. Based on this survey of the principal accountability mechanisms the Commission then draws some conclusions.

56. In 2009, it was reported that the criminal justice system in the CAR was widely considered to be dysfunctional:

The justice system is plagued by a lack of resources, severely limiting its capacity to address impunity. Human resources are minimal in the capital, and nearly non-existent in the rest of the country. In Bangui, the public prosecutor's office has just two prosecutors for criminal cases. ... Across the country, there are not enough buildings to house courtrooms and offices of judges and key personnel. Basic equipment is in short supply. |9|

57. Over the past two years, however, an already entirely inadequate and dramatically under-resourced legal system was further degraded and undermined. Police and judges were attacked and often forced to flee, some were even killed, |10| facilities were ransacked, equipment stolen or destroyed, and many of the official police and court records were intentionally destroyed. These attacks on the personnel and physical infrastructure of the justice system have further exacerbated the deeper structural problems that have, according to most observers and participants with whom the Commission spoke, long afflicted the judiciary. These include the tendency to select and appoint judges on the basis of their tribal or other affiliations and connections to the powerful, and an arbitrary approach to the careers of judges and prosecutors based on favouritism and rewards. The system is also rife with corruption at all levels, from the police and gendarmes who fail to collect evidence or later make it disappear, to the prosecutors, through the highest levels of the judiciary.

58. In addition, the past two years have seen a further diminution in the already very limited reach of the judicial system outside of Bangui. Similarly, the police and gendarmerie are barely present in the rest of the country. One knowledgeable observer of the justice system told the Commission that "in the interior of the country, nothing is working. The situation is chaotic due to the complete absence of authorities and respect for law and order. " The Bar consists of a total of 122 registered lawyers, all of whom are based in Bangui. In addition, the detention and prison systems were almost totally destroyed during the past two years, and the few facilities that currently exist are managed by or with the strong support of, the international forces.

59. This brief overview illustrates the nature and extent of the challenges that must be tackled by those seeking to build a system capable of attacking impunity. During the period under review, several attempts have been made to reinvigorate the justice sector, but they have had very limited success to date. Decree No. 13-100 of 20 May 2013 created a mixed commission of inquiry to investigate crimes and human rights violations committed since 2004. But this initiative was widely criticized because the commission's independence was not guaranteed, and it was not given the resources or premises needed to carry out its work. |11| It was reported to have received dozens of complaints and requests for damages from victims, but it is not clear that it succeeded in dealing with any of these issues before it was disbanded. |12|

60. In April 2014, the Transitional authorities created by decree the Cellule spéciale d'enquête et d'instruction (CSEI, or Special Investigation and Instruction Unit) to investigate and prosecute those responsible for serious crimes since 1 January 2004. Under the direction of the Prosecutor-General of the Court of Appeal, the Unit should be composed of judges and prosecutors, as well as twenty judicial police officers from the Gendarmerie and the national police. This initiative was widely welcomed by civil society and the legal profession, but the Prosecutor-General told the Commission in late August 2014 that no resources had been allocated to enable him to begin his work.

61. Several conclusions suggest themselves to the Commission. First, there is a genuine commitment on the part of some actors at the national level to tackle the impunity that has characterized the past decade. Second, there is a small group of judges and prosecutors who would be capable of contributing significantly to these initiatives. Third, the lack of resources and material support has, so far, been fatal to the initiatives that have been taken. It seems clear therefore that the support of the international community will be indispensable going forward.

62. Among the Security Council's priority concerns in creating MINUSCA were the protection of civilians and the provision of support for national and international justice and the rule of law. The Council thus provided that MINUSCA may, "within the limits of its capacities and areas of deployment, at the formal request of the Transitional Authorities and in areas where national security forces are not present or operational, adopt urgent temporary measures on an exceptional basis ... to maintain basic law and order and fight impunity." The measures were, however, to be limited in scope, time bound and consistent with the overall objectives of the mission.

63. Pursuant to this authority, a Memorandum of Intent was signed on 5 and 7 August 2014 by the Minister of Justice of the CAR and the Special Representative of the Secretary-General which commits the Government to establishing, by law, a Special Criminal Court. The court's jurisdiction will apply throughout the CAR and its remit is to conduct preliminary investigations and judicial examinations to try "serious crimes, including serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law, including conflict-related sexual violence as well as grave violations of the rights of the child, that constitute a threat to peace, stability or security" in the CAR. |13|

64. The agreement does not envisage the creation of a new international court, but rather a special court within the legal system of the CAR, according to the modalities specified in the memorandum, and pursuant to necessary legislative and regulatory measures to be adopted by the Government. It spells out the composition of the court, and especially the balance between national judges and prosecutors and international appointees.

65. It is not for the Commission to comment on the details of this agreement, but several observations are in order. The memorandum does not specify the jurisdiction ratione temporis, and could thus be interpreted as suggesting that no retrospective application is envisaged. This would prevent the court from contributing to efforts to ensure accountability for past crimes and is presumably not the intent of the agreement. Nor is the applicable law spelled out, which could be problematic to the extent that the existing CAR Penal Code does not mirror the provisions of the Rome Statute. But it may be presumed that the necessary legislative measures that are now being discussed will ensure clarity on this issue. Finally, the memorandum states that the arrangements shall be without prejudice to the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court in current or future investigations. But there will still be a need to reflect on the most effective ways in which to ensure that these two undertakings complement one another.

66. In principle, the Commission considers that the proposal to create a Special Criminal Court is highly desirable. It seems clear from past experience with purely national accountability initiatives that they are unlikely to succeed in the absence of the various advantages that can be derived from a more internationalized or hybrid effort. But past experience also counsels that the provision of adequate resources, provided by the national authorities but especially by the international community, will be a sine qua non for the success of the Special Criminal Court.

C. The Sanctions Committee and the Panel of Experts

67. By the same resolution that established this Commission, the Security Council imposed a sanctions regime on the CAR, and established a Sanctions Committee and a Panel of Experts to monitor and report on implementation of the sanctions. The resolution envisaged the imposition of targeted measures, including travel bans and assets freezes, against individuals who act to undermine the peace, stability and security, including by engaging in acts that threaten or violate transitional agreements, or by engaging or providing, support for actions that threaten or impede the political process or fuel violence, including through violations of human rights and international humanitarian law, the recruitment and use of children in armed conflict in violation of applicable international law, sexual violence, or supporting the illegal armed groups or criminal networks through the illicit exploitation of natural resources, including diamonds, or by violating the arms embargo.

68. The Panel of Experts has submitted two reports in the course of 2014. |14| As of 4 November 2014 the Committee had imposed sanctions on three individuals: François Bozizé, Levy Yakété, and Nourredine Adam. |15|

69. While the reports of the Panel are immensely helpful in understanding what is happening in the CAR, and the steps taken by the Sanctions Committee are important in a variety of ways, these measures are no substitute for the criminal accountability that is the focus of the present report.

D. The International Criminal Court

70. As previously noted, the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court has concluded that there is a reasonable basis, in accordance with Article 53 of the Rome Statute, to proceed with an investigation of crimes committed since 1 August 2012. Article 1 of the Statute provides that the Court's jurisdiction shall be complementary to that of national criminal jurisdictions, and Article 5 specifies that it shall be limited to the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole.

71. It is not for the Commission to undertake a detailed analysis of the relationship between the work of the International Criminal Court and that of the Special Criminal Court. On the one hand, the latter will be able to try many more alleged perpetrators, has the advantage of being closer to the local population, and will be able to establish important precedents that should continue to guide future judicial efforts to ensure accountability. On the other hand, it will not be ideally situated to handle some of the most controversial cases involving the most serious crimes and there are many reasons why the ICC should assume jurisdiction over that handful of cases. Suffice it to say that there are important precedents which demonstrate that the ICC and national courts can effectively and constructively share the responsibility for attacking impunity in such situations. In any event, it is clear that if the State, on the basis of the work of the Special Criminal Court and other relevant judicial bodies, can be deemed to be unwilling or unable genuinely to carry out the investigations or prosecutions required, the ICC will be empowered under article 17 of the Rome Statute to step in.

72. Several conclusions emerge from this overview of the existing justice system and of the arrangements that are in place or being set in train to strengthen and complement it. First, while noting the devastation of the policing, judicial, and prison systems that occurred over the past two years, it is essential to acknowledge that the CAR has a core group of trained lawyers, prosecutors and judges who are capable of forming the backbone of a newly revitalized system. The Commission emphasizes the importance of building upon this foundation, rather than seeking to go around it.

73. Second, in looking ahead, there is a need to strike a balance between the roles to be played by domestic and international actors. There are strong reasons why there needs to be an international component and these should not be underestimated. But there are also strong reasons why the domestic judiciary needs to be strengthened, to be consulted and fully involved, and to emerge from the process in a way that ensures that it is capable of maintaining the legacy of accountability beyond the stage at which the international community is no longer integrally involved.

74. Third, impunity will not be overcome unless both the Transitional authorities and the international community are prepared to pay for it. In April 2014, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, speaking in Bangui, concluded that there was "total impunity, no justice, no law and order apart from that provided by foreign troops". She added that "[c]reating an effective justice system, prisons, police forces and other key State institutions, virtually from scratch, is a massive and complex enterprise that cannot be done on the cheap. " The international community has already made a major commitment to the CAR. It would be unfortunate if this did not include sufficient funds to enable the Special Criminal Court to work effectively and to develop in such a way that it contributes to the long-term strengthening of the country's judicial system.

75. Fourth, any sustainable effort to ensure that impunity is eliminated will require that adequate attention is given to extending the reach of the justice system, broadly defined, well beyond Bangui and providing adequate coverage throughout the country as a whole. The Commission notes in that regard the proposal by the Panel of Experts for mobile courts. |16|

76. Fifth, the Commission perceives a gap between the commitments expressed by the Security Council and the needs identified by the Secretary-General, on the one hand, and the practical measures contemplated to date, on the other. The Secretary-General reported in November 2014 that the key antagonists "continue to operate in total impunity" in a situation that remains "highly volatile". He notes that "tackling impunity remains imperative." |17| But it is not clear that the urgent transitional measures upon which almost all hopes of tackling impunity seem to be pinned can be considered sufficient. The Transition in the CAR is scheduled to be completed by August 2015. By that time it is highly unlikely that many prosecutions will have been undertaken, let alone completed. The Commission therefore believes that it is essential for plans to be put in place urgently for a full-fledged hybrid court to take over from the UTM measures that are, by definition, required to be only temporary.

77. In conversations with some policy-makers and officials who are debating the shape of future arrangements, several arguments have been invoked to explain why the international community should not fund an ongoing internationalized judicial mechanism. One is that only a few thousand persons were killed. But this figure is certainly a gross under-estimate and entirely fails to capture the scope of the tragedy that has beset the CAR. Another argument is that such a mechanism would be immensely costly. It is true that other international mechanisms have not come cheaply, but impunity will not be ended in the absence of an effective and enduring mechanism, and ways of keeping the costs manageable could certainly be found.

VII. Conclusions and Recommendations

78. The Commission was established in response to horrendous abuses and to fears that the conflict in the CAR could turn into a genocidal killing spree. The fact that the Commission has concluded that the threshold requirement to prove the existence of the necessary element of genocidal intent has not been established in relation to any of the actors in the conflict does not in any way diminish the seriousness of crimes that have been committed and documented in this report. Nor does it give any reason to assume that in the future the risk of grave crimes, including genocide, will inevitably be averted. At the time of completion of this report there continues to be major instability in many parts of the country, including in Bangui. Acts of violence, including serious violations of human rights and humanitarian law, continue to be perpetrated and the principal actors clearly retain a significant capacity to reignite the situation and trigger a renewed cycle of killings as well as a range of other serious abuses. There is no doubt that the forceful action taken by the Security Council in the resolution by which it created this Commission, and the mandate that was subsequently given to MINUSCA, were essential in order to prevent an even greater explosion of violence than has been documented in this report. But continued vigilance is essential.

79. A question that inevitably arises in this context concerns the number of killings that have occurred in the course of the recent conflict. While various estimates are available in the public domain, usually ranging from 3,000 to 6,000 during the less than two years covered by the present report, the Commission wishes to underscore that any such estimates are unavoidably based on extremely limited and selective information. |18| The Commission considers that, under the circumstances, any such statistics must represent a radical under-estimate of the actual number of individuals who have lost their lives during this period as a result of human rights and humanitarian law abuses. |19| For those reasons the Commission has opted not to speculate on the numbers killed or the numbers subjected to other serious abuses. Narrowly-focused statistics of this sort cannot hope to capture the humanitarian disaster that has overtaken the CAR over the past two years, nor can they help to predict the scale of the continuing risks of large-scale violence.

80. The Commission wishes to underscore its conclusion that one of the most urgent tasks for the national authorities, working with the full support of the international community, is to end the impunity that has been enjoyed over many years by the vast majority of those who have committed serious violations of human rights law and international humanitarian law in the Central African Republic. This track record of consistent and uninterrupted impunity has established an expectation that perpetrators will not be punished. This in turn has provided an incentive for perpetrators to remain active in order to demonstrate that their participation in a future government is a necessary reward to induce them to cease their predations. The notions that killings or other abuses can pave the way to cabinet portfolios or other rewards must be definitively put to rest.

81. Impunity cannot be brought to an end solely through the prosecution of a handful of perpetrators, no matter how highly placed they might be, how serious the crimes they are alleged to have committed, or how central they might have been in the running of the criminal networks. |20| Rather, it requires a systematic effort to prosecute as many as possible of those who carried out serious violations, as well as those who ordered such acts. It also requires the building up of a legal system in the years ahead that will be able to demonstrate its capacity and willingness to investigate, prosecute, punish and incarcerate human rights violators, as well as being able to instill a degree of confidence on the part of the populace that the rule of law prevails in general.

1) To the National Transitional Government of the CAR

a) The Commission recommends that a high priority should be accorded to the rebuilding of all of the elements of an effective and functioning legal system. This includes a well-trained and well-armed police force, with a specialized investigative capacity, as well as an independent, qualified, and adequately resourced judiciary. The reach of these institutions must be national, and not confined solely to Bangui and its immediate surroundings;

b) The Central African Republic should become a party to both the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, along with the Optional Protocol to the latter.

c) Another proven technique for establishing accountability and undermining impunity is to create a truth commission. Given that many crimes will inevitably go unpunished in the conditions that have prevailed in the Central African Republic in recent years, it is important to seek to produce a detailed accounting of the crimes and human rights violations that have been committed and to permit the victims and their family members to recount their stories. While more elaborate goals have additionally been entrusted to some truth commissions established in other countries in the past few years, it is not clear that these models are likely to be affordable or successful in the short-term in this context. The key is to initiate a sustainable process that will, over time, grow and evolve in ways that are meaningful to the Central African community, rather than imitating models that have been developed in very different contexts. The Commission recommends that the Government invite the Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence to visit and make recommendations as to the most effective strategy to be pursued under the circumstances.

d) Another transitional justice-related issue which is also directly linked to the fight against impunity concerns the possibility of vetting candidates for national political office, including for the office of President of the Republic. The Commission recommends that the transitional authorities consider requiring such candidates to make a formal statement attesting to the fact that they were not responsible for or complicit in, serious crimes or gross violations of human rights and humanitarian law. In the event that such a declaration is subsequently shown to be false, the candidate should be ineligible to stand for election and, if already elected, should be disqualified from office. Such a system would require the authorities to consider what mechanisms and procedures could best be adopted to ensure a fair and just process.

e) Rape and other forms of sexual and gender-violence has occurred in alarming numbers. The authorities should make a special effort to prosecute the perpetrators and police in particular females should be trained to provide support in such situations in the future. Top priority, however, for the local community with international assistance should be on the provision of health care, education, economic programmes, special attention to women who have given birth to children as a result of rape, and the provision of trauma counselling to assist the healing of the victims and their affected family members.

2) To the National Transitional Government of the CAR and the MINUSCA

a) The Commission recommends that the National Transitional Government of the CAR, in cooperation with MINUSCA, should develop and implement a policy for restoring the property rights of those who were forced to flee as a result of communal violence, and whose homes and land were subsequently taken over by others. If, for any reason, the full restoration of such rights is not possible, a comprehensive program of compensation should be put in place, along with appropriate grievance mechanisms.

b) The independence of the Prosecutor to be appointed pursuant to the MOU will be critical to ensuring the success of the Special Criminal Court. The Prosecutor should draw up a list of priority cases to be pursued in the short-term as well as a longer-term strategy for ensuring accountability for the serious abuses that have been committed in recent years.

c) The conflict in the CAR has witnessed a very high number of incidents involving obstruction of efforts to deliver humanitarian assistance, as well as a high level of attacks on, and the killing of, aid workers, including medical personnel. The Commission recommends that the Government of the CAR, along with MINUSCA, should develop a more concerted policy for responding to, and seeking to deter, such violations of humanitarian neutrality.

The Commission recommends that in order to avoid any appearance of condoning impunity on the part of members of the international peace keeping forces who commit any violations or crimes, victims of these violations and their families should be kept informed of the sanctions or punitive measures that have been taken against the perpetrators of such violations.

a) One of the biggest challenges to securing accountability for human rights and humanitarian law violations will be the ability of the judicial system to ensure the protection of witnesses. Given the nature of the crimes, the passage of time, and the lack of forensic evidence in most cases, witness testimony will be key to building a strong case against alleged perpetrators. But in a country with extremely limited budgetary resources, and in which the extended family will also on occasion need some forms of protection, a major effort will be required to establish a witness protection program that meets the necessary criteria for success. |21| This will almost certainly require dedicated financial support from the international community, quite apart from any role that might be played in this regard by the International Criminal Court's witness protection program. Protecting witnesses also requires establishing strict confidentiality arrangements on the part of fact-finders and prosecutors.

b) The Commission considers that the agreement to create a Special Criminal Court is of major importance and it recommends to States and the international community to take all necessary measures, including the possibility of cooperating with existing international organisations, institutions, foundations, and non-governmental organizations in order to facilitate the successful establishment of the court, strengthen its capacity and reinforce its independence. The proximity of the national courts to the populace, their ability to send a meaningful message in relation to accountability, and their potential for dealing with a much larger number of perpetrators, argues strongly in favor of the international community making every effort to facilitate their primary role in upholding criminal accountability and providing remedies for victims.

c) The Commission also recommends that measures taken in 4 (b) above should be carefully designed, as far as possible, to make the maximum contribution to building up the capacity of the Central African court system. While there may be arguments for establishing a special court which is based outside the territory of the CAR, and thus away from the continuing instability and threats, such an initiative would not leave a lasting legacy in terms of a strengthened national legal system. Nor would it have the same impact as would a domestic tribunal that will demonstrate the capacity, independence and impartiality necessary to signal definitively that the days of impunity are over.

d) The Commission notes that the arrangements between MINUSCA and the CAR authorities to support the Special Criminal Court can only be of a temporary nature and that after August 2015, when the transition is to be completed, there is no assurance that such arrangements can or will be maintained. It also notes that the MOU establishing the SCC does not specifically give it retrospective application and focuses instead on future crimes rather than those of the past. The Commission therefore recommends that arrangements should be made to create an internationalized hybrid court, drawing on the experience in Sierra Leone and other States, to take the lead in establishing full accountability for the crimes described in this report.

e) The Commission notes that, after almost two years of analyzing the situation, the Prosecutor of the ICC announced on 24 September 2014 that she had concluded that there is a 'reasonable basis' to open an investigation into the situation in the Central African Republic ( "CAR II"). That investigation has now begun. The Commission considers that, under these conditions the principle of complementarity will be applied. It will be for the Central African courts, and particularly the Special Criminal Court, to show that they are both willing and able genuinely to carry out the investigation and prosecution of those alleged to have committed crimes against humanity or war crimes. In the event that the national courts are not able to satisfy this burden, the ICC should exercise its jurisdiction where appropriate.

f) If the ICC investigation is to be successful, it will need to be adequately resourced. The Assembly of the States Parties to the ICC should ensure that the necessary funds are available to undertake investigations that cover the alleged crimes of all of the parties to the conflict in the CAR. The Commission is aware that a significant number of allegations have been made of violations of international humanitarian law and human rights on the part of members of the various international peacekeeping forces deployed at various times in the CAR. Although it endeavoured to investigate some of these incidents, it was not able to reach definitive conclusions with regard to any particular case. The Commission considers, however, that in view of both the potential for such violations to occur and of the significant number of allegations made, there is a strong need to put in place a more effective system than that which currently exists. In order to achieve this outcome, The Commission recommends that a mechanism be established to receive and consider complaints alleging human rights violations by UN peace-keeping forces. The process that was put in place in Kosovo could usefully be adapted for this purpose.

5) To the Secretary-General of the United Nations

a) The Secretary-General should ensure the full applicability in practice of the United Nations Human Rights Due Diligence Policy to the regional peacekeeping forces with which the UN cooperates.

b) The Secretary-General's periodic reports on peace-keeping operations in the CAR should include an analysis of any violations that are alleged to have been committed by both UN peace-keepers and non-UN peacekeepers authorized by the Security Council.

c) The Commission leaves the Secretary-General the decision as to which judicial bodies, if any, should be provided with access to the confidential materials. It notes, however, that those materials could be of relevance to the inquiries undertaken by the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, the relevant prosecutorial authorities in the CAR, and any internationalized tribunal that might be created in the future to consider issues of criminal responsibility in the CAR during the period under review.

6) To the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

a) The Commission joins the Panel of Experts in calling upon the OHCHR to collaborate more effectively in the future with investigations being carried out by other international actors. In particular, the Office should ensure that clear policy guidelines are in place to ensure that all relevant information can be shared with commissions of inquiries, panels of experts, and other comparable actors. To the extent that issues of confidentiality are considered to arise, a protocol should immediately be developed to address this concern.