| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

Feb18

Nuclear Posture Review 2018

Back to topCONTENTS

SECRETARY'S PREFACE

On January 27, 2017, the President directed the Department of Defense to conduct a new Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) to ensure a safe, secure, and effective nuclear deterrent that protects the homeland, assures allies and above all, deters adversaries. This review comes at a critical moment in our nation's history, for America confronts an international security situation that is more complex and demanding than any since the end of the Cold War. In this environment, it is not possible to delay modernization of our nuclear forces if we are to preserve a credible nuclear deterrent–ensuring that our diplomats continue to speak from a position of strength on matters of war and peace.

For decades, the United States led the world in efforts to reduce the role and number of nuclear weapons. The 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) set a ceiling of 6,000 accountable strategic nuclear warheads – a deep reduction from Cold War highs. Shorter-range nuclear weapons were almost entirely eliminated from America's nuclear arsenal in the early 1990s. The 2002 Strategic Offensive Reduction Treaty and the 2010 New START Treaty further lowered strategic nuclear force levels to 1,550 accountable warheads. During this time, the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile drew down by more than 85 percent from its Cold War high. Many hoped conditions had been set for even deeper reductions in global nuclear arsenals, and, ultimately, for their elimination.

While Russia initially followed America's lead and made similarly sharp reductions in its strategic nuclear forces, it retained large numbers of non-strategic nuclear weapons. Today, Russia is modernizing these weapons as well as its other strategic systems. Even more troubling has been Russia's adoption of military strategies and capabilities that rely on nuclear escalation for their success. These developments, coupled with Russia's seizure of Crimea and nuclear threats against our allies, mark Moscow's decided return to Great Power competition.

China, too, is modernizing and expanding its already considerable nuclear forces. Like Russia, China is pursuing entirely new nuclear capabilities tailored to achieve particular national security objectives while also modernizing its conventional military, challenging traditional U.S. military superiority in the Western Pacific.

Elsewhere, the strategic picture brings similar concerns. North Korea's nuclear provocations threaten regional and global peace, despite universal condemnation in the United Nations. Iran's nuclear ambitions remain an unresolved concern. Globally, nuclear terrorism remains a real danger.

We must look reality in the eye and see the world as it is, not as we wish it to be. This NPR reflects the current, pragmatic assessment of the threats we face and the uncertainties regarding the future security environment.

Given the range of potential adversaries, their capabilities and strategic objectives, this review calls for a flexible, tailored nuclear deterrent strategy. This review calls for the diverse set of nuclear capabilities that provides an American President flexibility to tailor the approach to deterring one or more potential adversaries in different circumstances.

For any President, the use of nuclear weapons is contemplated only in the most extreme circumstances to protect our vital interests and those of our allies.

Nuclear forces, along with our conventional forces and other instruments of national power, are therefore first and foremost directed towards deterring aggression and preserving peace. Our goal is to convince adversaries they have nothing to gain and everything to lose from the use of nuclear weapons.

In no way does this approach lower the nuclear threshold. Rather, by convincing adversaries that even limited use of nuclear weapons will be more costly than they can tolerate, it in fact raises that threshold.

To this end, this review confirms the findings of previous NPRs that the nuclear triad–supported by North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) dual-capable aircraft and a robust nuclear command, control, and communications system–is the most cost-effective and strategically sound means of ensuring nuclear deterrence. The triad provides the President flexibility while guarding against technological surprise or sudden changes in the geopolitical environment. To remain effective, however, we must recapitalize our Cold War legacy nuclear forces.

By the time we complete the necessary modernization of these forces, they will have served decades beyond their initial life expectancy. This review affirms the modernization programs initiated during the previous Administration to replace our nuclear ballistic missile submarines, strategic bombers, nuclear air-launched cruise missiles, ICBMs, and associated nuclear command and control. Modernizing our dual-capable fighter bombers with next-generation F-35 fighter aircraft will maintain the strength of NATO's deterrence posture and maintain our ability to forward deploy nuclear weapons, should the security situation demand it.

Recapitalizing the nuclear weapons complex of laboratories and plants is also long past due; it is vital we ensure the capability to design, produce, assess, and maintain these weapons for as long as they are required. Due to consistent underfunding, significant and sustained investments will be required over the coming decade to ensure that National Nuclear Security Administration will be able to deliver the nuclear weapons at the needed rate to support the nuclear deterrent into the 2030s and beyond.

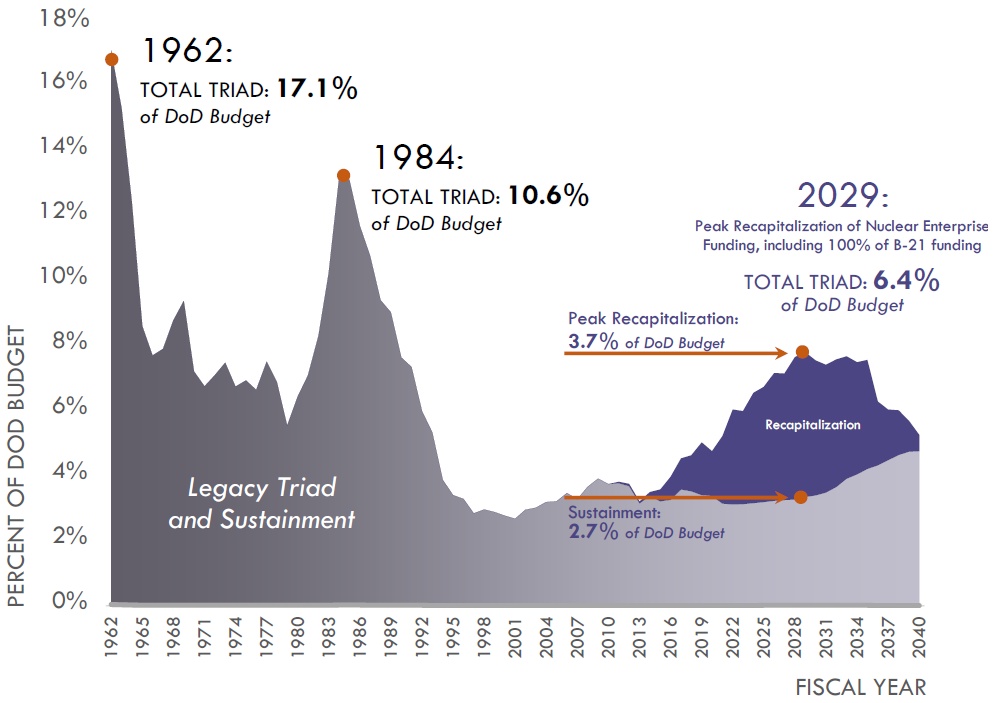

Maintaining an effective nuclear deterrent is much less expensive than fighting a war that we were unable to deter. Maintenance costs for today's nuclear deterrent are approximately three percent of the annual defense budget. Additional funding of another three to four percent, over more than a decade, will be required to replace these aging systems. This is a top priority of the Department of Defense. We are mindful of the sustained financial commitment and gratefully recognize the ongoing support of the American people and the United States Congress for this important mission.

While we will be relentless in ensuring our nuclear capabilities are effective, the United States is not turning away from its long-held arms control, non-proliferation, and nuclear security objectives. Our commitment to the goals of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) remains strong. Yet we must recognize that the current environment makes further progress toward nuclear arms reductions in the near term extremely challenging. Ensuring our nuclear deterrent remains strong will provide the best opportunity for convincing other nuclear powers to engage in meaningful arms control initiatives.

This review rests on a bedrock truth: nuclear weapons have and will continue to play a critical role in deterring nuclear attack and in preventing large-scale conventional warfare between nuclear-armed states for the foreseeable future. U.S. nuclear weapons not only defend our allies against conventional and nuclear threats, they also help them avoid the need to develop their own nuclear arsenals. This, in turn, furthers global security.

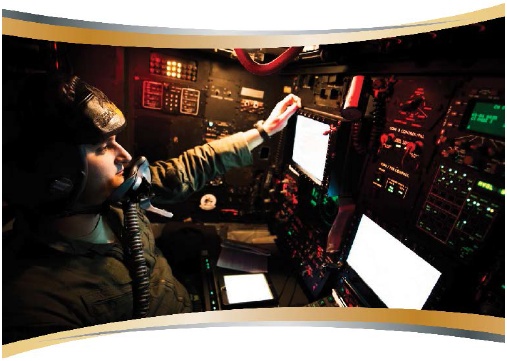

I would be remiss if I did not acknowledge the vital role our Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, Marines, Coast Guardsmen, and civilians play in maintaining a safe, secure, and ready nuclear force. Without their ceaseless and often unheralded efforts, America would not possess a nuclear deterrent. At the end of the day, deterrence comes down to the men and women in uniform – in silos, in the air, and beneath the sea.

To each and every one of them, I wish to express my personal respect and that of a grateful and safe Nation.

Jim Mattis

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION

On January 27, 2017, President Donald Trump directed Secretary of Defense James Mattis to initiate a new Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). The President made clear that his first priority is to protect the United States, allies, and partners. He also emphasized both the long-term goal of eliminating nuclear weapons and the requirement that the United States have modern, flexible, and resilient nuclear capabilities that are safe and secure until such a time as nuclear weapons can prudently be eliminated from the world.

The United States remains committed to its efforts in support of the ultimate global elimination of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. It has reduced the nuclear stockpile by over 85 percent since the height of the Cold War and deployed no new nuclear capabilities for over two decades. Nevertheless, global threat conditions have worsened markedly since the most recent 2010 NPR, including increasingly explicit nuclear threats from potential adversaries. The United States now faces a more diverse and advanced nuclear-threat environment than ever before, with considerable dynamism in potential adversaries' development and deployment programs for nuclear weapons and delivery systems.

AN EVOLVING AND UNCERTAIN INTERNATIONAL SECURITY ENVIRONMENT

While the United States has continued to reduce the number and salience of nuclear weapons, others, including Russia and China, have moved in the opposite direction. They have added new types of nuclear capabilities to their arsenals, increased the salience of nuclear forces in their strategies and plans, and engaged in increasingly aggressive behavior, including in outer space and cyber space. North Korea continues its illicit pursuit of nuclear weapons and missile capabilities in direct violation of United Nations (U.N.) Security Council resolutions. Iran has agreed to constraints on its nuclear program in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Nevertheless, it retains the technological capability and much of the capacity necessary to develop a nuclear weapon within one year of a decision to do so.

There now exists an unprecedented range and mix of threats, including major conventional, chemical, biological, nuclear, space, and cyber threats, and violent non-state actors. These developments have produced increased uncertainty and risk.

This rapid deterioration of the threat environment since the 2010 NPR must now shape our thinking as we formulate policy and strategy, and initiate the sustainment and replacement of U.S. nuclear forces. This 2018 NPR assesses previous nuclear policies and requirements that were established amid a more benign nuclear environment and more amicable Great Power relations. It focuses on identifying the nuclear policies, strategy, and corresponding capabilities needed to protect America in the deteriorating threat environment that confronts the United States, allies, and partners. It is strategy driven and provides guidance for the nuclear force posture and policy requirements needed now and in the future.

The United States does not wish to regard either Russia or China as an adversary and seeks stable relations with both. We have long sought a dialogue with China to enhance our understanding of our respective nuclear policies, doctrine, and capabilities; to improve transparency; and to help manage the risks of miscalculation and misperception. We hope that China will share this interest and that meaningful dialogue can commence. The United States and Russia have in the past maintained strategic dialogues to manage nuclear competition and nuclear risks. Given Russian actions, including its occupation of Crimea, this constructive engagement has declined substantially. We look forward to conditions that would once again allow for transparent and constructive engagement with Russia.

Nevertheless, this review candidly addresses the challenges posed by Russian, Chinese, and other states' strategic policies, programs, and capabilities, particularly nuclear. It presents the flexible, adaptable, and resilient U.S. nuclear capabilities now required to protect the United States, allies, and partners, and promote strategic stability.

THE VALUE OF U.S. NUCLEAR CAPABILITIES

The fundamental reasons why U.S. nuclear capabilities and deterrence strategies are necessary for U.S., allied, and partner security are readily apparent. U.S. nuclear capabilities make essential contributions to the deterrence of nuclear and non-nuclear aggression. The deterrence effects they provide are unique and essential to preventing adversary nuclear attacks, which is the highest priority of the United States.

U.S. nuclear capabilities cannot prevent all conflict, and should not be expected to do so. But, they contribute uniquely to the deterrence of both nuclear and non-nuclear aggression. They are essential for these purposes and will be so for the foreseeable future. Non-nuclear forces also play essential deterrence roles, but do not provide comparable deterrence effects–as is reflected by past, periodic, and catastrophic failures of conventional deterrence to prevent Great Power war before the advent of nuclear deterrence. In addition, conventional forces alone are inadequate to assure many allies who rightly place enormous value on U.S. extended nuclear deterrence for their security, which correspondingly is also key to non-proliferation.

U.S. NUCLEAR CAPABILITIES AND ENDURING NATIONAL OBJECTIVES

The highest U.S. nuclear policy and strategy priority is to deter potential adversaries from nuclear attack of any scale. However, deterring nuclear attack is not the sole purpose of nuclear weapons. Given the diverse threats and profound uncertainties of the current and future threat environment, U.S. nuclear forces play the following critical roles in U.S. national security strategy. They contribute to the:

- Deterrence of nuclear and non-nuclear attack;

- Assurance of allies and partners;

- Achievement of U.S. objectives if deterrence fails; and

- Capacity to hedge against an uncertain future.

These roles are complementary and interrelated, and the adequacy of U.S. nuclear forces must be assessed against each role and the strategy designed to fulfill it. Preventing proliferation and denying terrorists access to finished weapons, material, or expertise are also key considerations in the elaboration of U.S. nuclear policy and requirements. These multiple roles and objectives constitute the guiding pillars for U.S. nuclear policy and requirements.

DETERRENCE OF NUCLEAR AND NON-NUCLEAR ATTACK

Effective U.S. deterrence of nuclear attack and non-nuclear strategic attack requires ensuring that potential adversaries do not miscalculate regarding the consequences of nuclear first use, either regionally or against the United States itself. They must understand that there are no possible benefits from non-nuclear aggression or limited nuclear escalation. Correcting any such misperceptions is now critical to maintaining strategic stability in Europe and Asia.

Potential adversaries must recognize that across the emerging range of threats and contexts: 1) the United States is able to identify them and hold them accountable for acts of aggression, including new forms of aggression; 2) we will defeat non-nuclear strategic attacks; and, 3) any nuclear escalation will fail to achieve their objectives, and will instead result in unacceptable consequences for them.

There is no "one size fits all" for deterrence. Consequently, the United States will apply a tailored and flexible approach to effectively deter across a spectrum of adversaries, threats, and contexts. Tailored deterrence strategies communicate to different potential adversaries that their aggression would carry unacceptable risks and intolerable costs according to their particular calculations of risk and cost.

U.S. nuclear capabilities, and nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3), must be increasingly flexible to tailor deterrence strategies across a range of potential adversaries and threats, and enable adjustments over time. Accordingly, the United States will maintain the range of flexible nuclear capabilities needed to ensure that nuclear or non-nuclear aggression against the United States, allies, and partners will fail to achieve its objectives and carry with it the credible risk of intolerable consequences for potential adversaries now and in the future.

To do so, the United States will sustain and replace its nuclear capabilities, modernize NC3, and strengthen the integration of nuclear and non-nuclear military planning. Combatant Commands and Service components will be organized and resourced for this mission, and will plan, train, and exercise to integrate U.S. nuclear and non-nuclear forces to operate in the face of adversary nuclear threats and employment. The United States will coordinate integration activities with allies facing nuclear threats and examine opportunities for additional allied burden sharing of the nuclear deterrence mission.

ASSURANCE OF ALLIES AND PARTNERS

The United States has formal extended deterrence commitments that assure European, Asian, and Pacific allies. Assurance is a common goal based on collaboration with allies and partners to deter or defeat the threats we face. No country should doubt the strength of our extended deterrence commitments or the strength of U.S. and allied capabilities to deter, and if necessary defeat, any potential adversary's nuclear or non-nuclear aggression. In many cases, effectively assuring allies and partners depends on their confidence in the credibility of U.S. extended nuclear deterrence, which enables most to eschew possession of nuclear weapons, thereby contributing to U.S. non-proliferation goals.

ACHIEVE U.S. OBJECTIVES SHOULD DETERRENCE FAIL

The United States would only consider the employment of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States, its allies, and partners. Nevertheless, if deterrence fails, the United States will strive to end any conflict at the lowest level of damage possible and on the best achievable terms for the United States, allies, and partners. U.S. nuclear policy for decades has consistently included this objective of limiting damage if deterrence fails.

HEDGE AGAINST AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE

The United States will continue efforts to create a more cooperative and benign security environment, but must also hedge against prospective and unanticipated risks. Hedging strategies help reduce risk and avoid threats that otherwise may emerge over time, including geopolitical, technological, operational, and programmatic. They also contribute to deterrence and can help reduce potential adversaries' confidence that they can gain advantage through a "break out" or expansion of nuclear capabilities. Given the increasing prominence of nuclear weapons in potential adversaries' defense policies and strategies, and the uncertainties of the future threat environment, U.S. nuclear capabilities and the ability to quickly modify those capabilities can be essential to mitigate or overcome risk, including the unexpected.

U.S. NUCLEAR ENTERPRISE PERSONNEL

Effective deterrence would be impossible without the thousands of members of the United States Armed Forces and civilian personnel who dedicate their professional lives to the deterrence of war and protecting the Nation. These exceptional men and women are held to the most rigorous standards and make the most vital contribution to U.S. nuclear capabilities and deterrence.

The Service members and civilians involved in the nuclear deterrence mission do so with little public recognition or fanfare. Theirs is an unsung duty of the utmost importance. They deserve the support of the American people for the safety, security, and stability they provide the Nation, and indeed the world. The Service reforms we have accordingly implemented were long overdue, and the Department of Defense remains fully committed to properly supporting the Service members who protect the United States against nuclear threats.

THE TRIAD: PRESENT AND FUTURE

Today's strategic nuclear triad, largely deployed in the 1980s or earlier, consists of: submarines (SSBNs) armed with submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM); land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM); and strategic bombers carrying gravity bombs and air-launched cruise missiles (ALCMs). The triad and non-strategic nuclear forces, with supporting NC3, provides diversity and flexibility as needed to tailor U.S. strategies for deterrence, assurance, achieving objectives should deterrence fail, and hedging.

The increasing need for this diversity and flexibility, in turn, is one of the primary reasons why sustaining and replacing the nuclear triad and non-strategic nuclear capabilities, and modernizing NC3, is necessary now. The triad's synergy and overlapping attributes help ensure the enduring survivability of our deterrence capabilities against attack and our capacity to hold at risk a range of adversary targets throughout a crisis or conflict. Eliminating any leg of the triad would greatly ease adversary attack planning and allow an adversary to concentrate resources and attention on defeating the remaining two legs. Therefore, we will sustain our legacy triad systems until the planned replacement programs are deployed.

The United States currently operates 14 OHIO-class SSBNs and will continue to take the steps needed to ensure that OHIO SSBNs remain operationally effective and survivable until replaced by the COLUMBIA-class SSBN. The COLUMBIA program will deliver a minimum of 12 SSBNs to replace the current OHIO fleet and is designed to provide required deterrence capabilities for decades.

The ICBM force consists of 400 single-warhead Minuteman III missiles deployed in underground silos and dispersed across several states. The United States has initiated the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program to begin the replacement of Minuteman III in 2029. The GBSD program will also modernize the 450 ICBM launch facilities that will support the fielding of 400 ICBMs.

The bomber leg of the triad consists of 46 nuclear-capable B-52H and 20 nuclear-capable B-2A "stealth" strategic bombers. The United States has initiated a program to develop and deploy the next-generation bomber, the B-21 Raider. It will first supplement, and eventually replace elements of the conventional and nuclear-capable bomber force beginning in the mid-2020s.

The B83-1 and B61-11 gravity bombs can hold at risk a variety of protected targets. As a result, both will be retained in the stockpile, at least until there is sufficient confidence in the B61-12 gravity bomb that will be available in 2020.

Beginning in 1982, B-52H bombers were equipped with ALCMs. Armed with ALCMs, the B-52H can stay outside adversary air defenses and remain effective. The ALCM, however, is now more than 25 years past its design life and faces continuously improving adversary air defense systems. The Long-Range Stand-Off (LRSO) cruise missile replacement program will maintain into the future the bomber force capability to deliver stand-off weapons that can penetrate and survive advanced integrated air defense systems, thus supporting the long-term effectiveness of the bomber leg.

The current non-strategic nuclear force consists exclusively of a relatively small number of B61 gravity bombs carried by F-15E and allied dual capable aircraft (DCA). The United States is incorporating nuclear capability onto the forward-deployable, nuclear-capable F-35 as a replacement for the current aging DCA. In conjunction with the ongoing life extension program for the B61 bomb, it will be a key contributor to continued regional deterrence stability and the assurance of allies.

FLEXIBLE AND SECURE NUCLEAR CAPABILITIES: AN AFFORDABLE PRIORITY

Throughout past decades, senior U.S. officials have emphasized that the highest priority of the Department of Defense is deterring nuclear attack and maintaining the nuclear capabilities necessary to do so. While cost estimates for the program to sustain and replace U.S. nuclear capabilities vary, even the highest of these projections place the highpoint of the future cost at approximately 6.4 percent of the current DoD budget. Maintaining and operating our current aging nuclear forces now requires between two and three percent of the DoD budget. The replacement program to rebuild the triad for decades of service will peak for several years at only approximately four percent beyond the ongoing two to three percent needed for maintenance and operations. This 6.4 percent of the current DoD budget required for the long-term replacement program represents less than one percent of the overall federal budget. This level of spending to replace U.S. nuclear capabilities compares favorably to the 10.6 percent of the DoD budget required during the last such investment period in the 1980s, which at the time was almost 3.7 percent of the federal budget, and the 17.1 percent of the DoD budget required in the early 1960s.

Given the criticality of effective U.S. nuclear deterrence to the safety of the American people, allies and partners there is no doubt that the sustainment and replacement program should be regarded as both necessary and affordable.

ENHANCING DETERRENCE WITH NON-STRATEGIC NUCLEAR CAPABILITIES

Existing elements of the nuclear force replacement program predate the dramatic deterioration of the strategic environment. To meet the emerging requirements of U.S. strategy, the United States will now pursue select supplements to the replacement program to enhance the flexibility and responsiveness of U.S. nuclear forces. It is a reflection of the versatility and flexibility of the U.S. triad that only modest supplements are now required in this much more challenging threat environment.

These supplements will enhance deterrence by denying potential adversaries any mistaken confidence that limited nuclear employment can provide a useful advantage over the United States and its allies. Russia's belief that limited nuclear first use, potentially including low-yield weapons, can provide such an advantage is based, in part, on Moscow's perception that its greater number and variety of non-strategic nuclear systems provide a coercive advantage in crises and at lower levels of conflict. Recent Russian statements on this evolving nuclear weapons doctrine appear to lower the threshold for Moscow's first-use of nuclear weapons. Russia demonstrates its perception of the advantage these systems provide through numerous exercises and statements. Correcting this mistaken Russian perception is a strategic imperative.

To address these types of challenges and preserve deterrence stability, the United States will enhance the flexibility and range of its tailored deterrence options. To be clear, this is not intended to, nor does it enable, "nuclear war-fighting." Expanding flexible U.S. nuclear options now, to include low-yield options, is important for the preservation of credible deterrence against regional aggression. It will raise the nuclear threshold and help ensure that potential adversaries perceive no possible advantage in limited nuclear escalation, making nuclear employment less likely.

Consequently, the United States will maintain, and enhance as necessary, the capability to forward deploy nuclear bombers and DCA around the world. We are committed to upgrading DCA with the nuclear-capable F-35 aircraft. We will work with NATO to best ensure–and improve where needed–the readiness, survivability, and operational effectiveness of DCA based in Europe.

Additionally, in the near-term, the United States will modify a small number of existing SLBM warheads to provide a low-yield option, and in the longer term, pursue a modern nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM). Unlike DCA, a low-yield SLBM warhead and SLCM will not require or rely on host nation support to provide deterrent effect. They will provide additional diversity in platforms, range, and survivability, and a valuable hedge against future nuclear "break out" scenarios.

DoD and National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) will develop for deployment a low-yield SLBM warhead to ensure a prompt response option that is able to penetrate adversary defenses. This is a comparatively low-cost and near term modification to an existing capability that will help counter any mistaken perception of an exploitable "gap" in U.S. regional deterrence capabilities.

In addition to this near-term step, for the longer term the United States will pursue a nuclear-armed SLCM, leveraging existing technologies to help ensure its cost effectiveness. SLCM will provide a needed non-strategic regional presence, an assured response capability. It also will provide an arms control compliant response to Russia's non-compliance with the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty, its non-strategic nuclear arsenal, and its other destabilizing behaviors.

In the 2010 NPR, the United States announced the retirement of its previous nuclear-armed SLCM, which for decades had contributed to deterrence and the assurance of allies, particularly in Asia. We will immediately begin efforts to restore this capability by initiating a capability study leading to an Analysis of Alternatives (AoA) for the rapid development of a modern SLCM.

These supplements to the planned nuclear force replacement program are prudent options for enhancing the flexibility and diversity of U.S. nuclear capabilities. They are compliant with all treaties and agreements, and together, they will: provide a diverse set of characteristics enhancing our ability to tailor deterrence and assurance; expand the range of credible U.S. options for responding to nuclear or non-nuclear strategic attack; and, enhance deterrence by signaling to potential adversaries that their limited nuclear escalation offers no exploitable advantage.

NUCLEAR COMMAND, CONTROL, AND COMMUNICATIONS MODERNIZATION

The United States must have an NC3 system that provides control of U.S. nuclear forces at all times, even under the enormous stress of a nuclear attack. NC3 capabilities must assure the integrity of transmitted information and possess the resiliency and survivability necessary to reliably overcome the effects of nuclear attack. During peacetime and crisis, the NC3 system performs five crucial functions: detection, warning, and attack characterization; adaptive nuclear planning; decision-making conferencing; receiving Presidential orders; and enabling the management and direction of forces.

Today's NC3 system is a legacy of the Cold War, last comprehensively updated almost three decades ago. It includes interconnected elements composed of warning satellites and radars; communications satellites, aircraft, and ground stations; fixed and mobile command posts; and the control centers for nuclear systems.

While once state-of-the-art, the NC3 system is now subject to challenges from both aging system components and new, growing 21st century threats. Of particular concern are expanding threats in space and cyber space, adversary strategies of limited nuclear escalation, and the broad diffusion within DoD of authority and responsibility for governance of the NC3 system, a function which, by its nature, must be integrated.

In light of the critical need to ensure our NC3 system remains survivable and effective, the United States will pursue a series of initiatives. This includes: strengthening protection against cyber threats, strengthening protection against space-based threats, enhancing integrated tactical warning and attack assessment, improving command post and communication links, advancing decision support technology, integrating planning and operations, and reforming governance of the overall NC3 system.

NUCLEAR WEAPONS INFRASTRUCTURE

An effective, responsive, and resilient nuclear weapons infrastructure is essential to the U.S. capacity to adapt flexibly to shifting requirements. Such an infrastructure offers tangible evidence to both allies and potential adversaries of U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities and thus contributes to deterrence, assurance, and hedging against adverse developments. It also discourages adversary interest in arms competition.

DoD generates military requirements for the nuclear warheads to be carried on delivery platforms. NNSA oversees the research, development, test, assessment, and production programs that respond to DoD warhead requirements.

Over the past several decades, the U.S. nuclear weapons infrastructure has suffered the effects of age and underfunding. Over half of NNSA's infrastructure is over 40 years old, and a quarter dates back to the Manhattan Project era. All previous NPRs highlighted the need to maintain a modern nuclear weapons infrastructure, but the United States has fallen short in sustaining a modern infrastructure that is resilient and has the capacity to respond to unforeseen developments. There now is no margin for further delay in recapitalizing the physical infrastructure needed to produce strategic materials and components for U.S. nuclear weapons. Just as our nuclear forces are an affordable priority, so is a resilient and effective nuclear weapons infrastructure, without which our nuclear deterrent cannot exist.

The U.S. must have the ability to maintain and certify a safe, secure, and effective nuclear arsenal. Synchronized with DoD replacement programs, the United States will sustain and deliver on-time the warheads needed to support both strategic and non-strategic nuclear capabilities by:

- Completing the W76-1 Life Extension Program (LEP) by Fiscal Year (FY) 2019;

- Completing the B61-12 LEP by FY2024;

- Completing the W88 alterations by FY2024;

- Synchronizing NNSA's W80-4 life extension, with DoD's LRSO program and completing the W80-4 LEP by FY2031;

- Advancing the W78 warhead replacement one year to FY19 to support fielding on GBSD by 2030 and investigate the feasibility of fielding the nuclear explosive package in a Navy flight vehicle;

- Sustaining the B83-1 past its currently planned retirement date until a suitable replacement is identified; and,

- Exploring future ballistic missile warhead requirements based on the threats and vulnerabilities of potential adversaries, including the possibility of common reentry systems between Air Force and Navy systems.

The United States will pursue initiatives to ensure the necessary capability, capacity, and responsiveness of the nuclear weapons infrastructure and the needed skills of the workforce, including the following:

- Pursue a joint DoD and Department of Energy advanced technology development capability to ensure that efforts are appropriately integrated to meet DoD needs.

- Provide the enduring capability and capacity to produce plutonium pits at a rate of no fewer than 80 pits per year by 2030. A delay in this would result in the need for a higher rate of pit production at higher cost.

- Ensure that current plans to reconstitute the U.S. capability to produce lithium compounds are sufficient to meet military requirements.

- Fully fund the Uranium Processing Facility and ensure availability of sufficient low enriched uranium to meet military requirements.

- Ensure the necessary reactor capacity to produce an adequate supply of tritium to meet military requirements.

- Ensure continuity in the U.S. capability to develop and manufacture secure, trusted strategic radiation-hardened microelectronic systems beyond 2025 to support stockpile modernization.

- Rapidly pursue the Stockpile Responsiveness Program established by Congress to expand opportunities for young scientists and engineers to advance warhead design, development, and production skills.

- Develop an NNSA roadmap that sizes production capacity to modernization and hedging requirements.

- Retain confidence in nuclear gravity bombs needed to meet deterrence needs.

- Maintain and enhance the computational, experimental, and testing capabilities needed to annually assess nuclear weapons.

COUNTERING NUCLEAR TERRORISM

The U.S. strategy to combat nuclear terrorism encompasses a wide range of activities that comprise a defense-in-depth against current and emerging dangers. Under this multilayered approach, the United States strives to prevent terrorists from obtaining nuclear weapons or weapons-usable materials, technology, and expertise; counter their efforts to acquire, transfer, or employ these assets; and respond to nuclear incidents, by locating and disabling a nuclear device or managing the consequences of a nuclear detonation.

For effective deterrence, the United States will hold fully accountable any state, terrorist group, or other non-state actor that supports or enables terrorist efforts to obtain or employ nuclear devices. Although the role of U.S. nuclear weapons in countering nuclear terrorism is limited, our adversaries must understand that a terrorist nuclear attack against the United States or its allies and partners would qualify as an "extreme circumstance" under which the United States could consider the ultimate form of retaliation.

NON-PROLIFERATION AND ARMS CONTROL

Effective nuclear non-proliferation and arms control measures can support U.S., allied, and partner security by controlling the spread of nuclear materials and technology; placing limits on the production, stockpiling and deployment of nuclear weapons; decreasing misperception and miscalculation; and avoiding destabilizing nuclear arms competition. The United States will continue its efforts to: 1) minimize the number of nuclear weapons states, including by maintaining credible U.S. extended nuclear deterrence and assurance; 2) deny terrorist organizations access to nuclear weapons and materials; 3) strictly control weapons-usable material, related technology, and expertise; and 4) seek arms control agreements that enhance security, and are verifiable and enforceable.

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) is a cornerstone of the nuclear non-proliferation regime. It plays a positive role in building consensus for non-proliferation and enhances international efforts to impose costs on those that would pursue nuclear weapons outside the Treaty.

However, nuclear non-proliferation today faces acute challenges. Most significantly, North Korea is pursuing a nuclear path in direct contravention of the NPT and in direct opposition to numerous U.N. Security Council resolutions. Beyond North Korea looms the challenge of Iran. Although the JCPOA may constrain Tehran's nuclear weapons program, there is little doubt Iran could achieve a nuclear weapon capability rapidly if it decides to do so.

In continuing support of nuclear non-proliferation, the United States will work to increase transparency and predictability, where appropriate, to avoid potential miscalculation among nuclear weapons states and other possessor states through strategic dialogues, risk-reduction communications channels, and the sharing of best practices related to nuclear weapons safety and security.

Although the United States will not seek ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, it will continue to support the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organization Preparatory Committee as well as the International Monitoring System and the International Data Center. The United States will not resume nuclear explosive testing unless necessary to ensure the safety and effectiveness of the U.S. nuclear arsenal, and calls on all states possessing nuclear weapons to declare or maintain a moratorium on nuclear testing.

Arms control can contribute to U.S. security by helping to manage strategic competition among states. It can foster transparency, understanding, and predictability in adversary relations, thereby reducing the risk of misunderstanding and miscalculation.

The United States is committed to arms control efforts that advance U.S., allied, and partner security; are verifiable and enforceable; and include partners that comply responsibly with their obligations. Such arms control efforts can contribute to the U.S. capability to sustain strategic stability. Further progress is difficult to envision, however, in an environment that is characterized by continuing significant non-compliance with existing arms control obligations and commitments, and by potential adversaries who seek to change borders and overturn existing norms.

In this regard, Russia continues to violate a series of arms control treaties and commitments. In the nuclear context, the most significant Russian violation involves a system banned by the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty. In a broader context, Russia is either rejecting or avoiding its obligations and commitments under numerous agreements, and has rebuffed U.S. efforts to follow the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) with another round of negotiated reductions and to pursue reductions in non-strategic nuclear forces.

Nevertheless, New START is in effect through February 2021, and with mutual agreement may be extended for up to five years, to 2026. The United States already has met the Treaty's central limits which go into force on February 5, 2018, and will continue to implement the New START Treaty.

The United States remains willing to engage in a prudent arms control agenda. We are prepared to consider arms control opportunities that return parties to compliance, predictability, and transparency, and remain receptive to future arms control negotiations if conditions permit and the potential outcome improves the security of the United States, its allies, and partners.

I. INTRODUCTION TO U.S. NUCLEAR POLICY AND STRATEGY

"The Secretary shall initiate a new Nuclear Posture Review to ensure that the United States nuclear deterrent is modern, robust, flexible, resilient, ready and appropriately tailored to deter 21st-century threats and reassure our allies."

President Donald Trump, 2017

On January 27, 2017, President Donald Trump directed Secretary of Defense James Mattis to initiate a new Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). The President made clear that his first priority is to protect the United States, allies and partners. He emphasized both the long-term goal of eliminating nuclear weapons and the requirement that the United States have modern, flexible, and resilient nuclear capabilities that are safe, secure, and effective until such a time as nuclear weapons can prudently be eliminated from the world.

The Ohio-class ballistic missile submarine USS Nebraska (SSBN 739) transits into open ocean during an underway for training and proficiency. Nebraska is one of eight ballistic missile submarines stationed at Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor and recently completed an extended major maintenance period, including an engineered refueling overhaul, at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility. (U.S. Navy photo)

The United States remains committed to its efforts in support of the ultimate global elimination of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. It has negotiated multiple arms control treaties and has fully abided by its treaty commitments. In addition, for over two decades the United States has deployed no new nuclear capabilities, advanced nuclear reduction and non-proliferation initiatives to Russia and others, and strengthened alliance commitments and capabilities to safeguard international order and prevent further proliferation of nuclear weapons.

Nevertheless, global threat conditions have worsened markedly since the most recent, 2010 NPR. There now exist an unprecedented range and mix of threats, including major conventional, chemical, biological, nuclear, space, and cyber threats, and violent non-state actors. International relations are volatile. Russia and China are contesting the international norms and order we have worked with our allies, partners, and members of the international community to build and sustain. Some regions are marked by persistent disorder that appears likely to continue and possibly intensify. These developments have produced increased uncertainty and risk, demanding a renewed seriousness of purpose in deterring threats and assuring allies and partners.

While the United States has continued to reduce the number and salience of nuclear weapons, others, including Russia and China, have moved in the opposite direction. Russia has expanded and improved its strategic and non-strategic nuclear forces. China's military modernization has resulted in an expanded nuclear force, with little to no transparency into its intentions. North Korea continues its illicit pursuit of nuclear weapons and missile capabilities in direct violation of United Nations (U.N.) Security Council resolutions. Russia and North Korea have increased the salience of nuclear forces in their strategies and plans and have engaged in increasingly explicit nuclear threats. Along with China, they have also engaged in increasingly aggressive behavior in outer space and cyber space.

As a result, the 2018 NPR assesses recent nuclear policies and requirements that were established amid a more benign nuclear environment and more amicable Great Power relations. It focuses on identifying the nuclear policies, strategy, and corresponding capabilities needed to protect America, its allies, and partners in a deteriorating threat environment. It is strategy driven and provides guidance for the nuclear force structure and policy requirements needed now and in the future to maintain peace and stability in a rapidly shifting environment with significant future uncertainty.

The current threat environment and future uncertainties now necessitate a national commitment to maintain modern and effective nuclear forces, as well as the infrastructure needed to support them. Consequently, the United States has initiated a series of programs to sustain and replace existing nuclear capabilities before they reach the end of their service lives. These programs are critical to preserving our ability to deter threats to the Nation.

II. AN EVOLVING AND UNCERTAIN INTERNATIONAL SECURITY ENVIRONMENT

"For the first time in 25years, the United States is facing a return to great power competition. Russia and China both have advanced their military capabilities to act as global powers... Others are now pursuing advanced technology, including military technologies that were once the exclusive province of great powers – this trend will only continue."

Admiral Richardson, Chief of Naval Operations "A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority," 2017

Each previous NPR emphasized that changes in the international security environment shape U.S. nuclear policy, strategy, and posture. The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff recently assessed that the emerging security environment, "can be described by simultaneous and connected challenges–contested norms and persistent disorder." The rapid deterioration of the threat environment since the 2010 NPR must now shape our thinking as we formulate policy and strategy, while we sustain and replace U.S. nuclear capabilities.

The last NPR was based on a number of key findings and expectations regarding the nature of the security environment that have not since been realized. Most notably, it reflected the expectations that:

- The prospects for military confrontation with Russia, or among Great Powers, had declined and would continue to decline dramatically.

- The United States could decrease incentives for nuclear proliferation globally and reduce the likelihood of nuclear weapons employment by reducing both the role of nuclear weapons in U.S. national security strategy and the number of nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal. This was based in part on the aspiration that if the United States took the lead in reducing nuclear arms, other nuclear-armed states would follow.

U.S. efforts to reduce the roles and numbers of nuclear weapons, and convince other states to do the same, have included reducing the U.S. nuclear stockpile by over 85 percent since its Cold War high. Potential adversaries, however, have expanded and modernized their nuclear forces. This and additional negative developments in the international security environment presents new and serious challenges to U.S., allied and partner security. They have rendered our earlier, sanguine findings and expectations an outdated basis for U.S. nuclear policy, strategy, and posture going forward.

THE RETURN OF GREAT POWER COMPETITION

Since 2010 we have seen the return of Great Power competition. To varying degrees, Russia and China have made clear they seek to substantially revise the post-Cold War international order and norms of behavior. Russia has demonstrated its willingness to use force to alter the map of Europe and impose its will on its neighbors, backed by implicit and explicit nuclear first-use threats. Russia is in violation of its international legal and political commitments that directly affect the security of others, including the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, the 2002 Open Skies Treaty, and the 1991 Presidential Nuclear Initiatives. Its occupation of Crimea and direct support for Russia-led forces in Eastern Ukraine violate its commitment to respect the territorial integrity of Ukraine that they made in the 1994 Budapest Memorandum. China meanwhile has rejected the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration Tribunal that found China's maritime claims in the South China Sea to be without merit and some of its related activities illegal under the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea and customary international law. Subsequently, China has continued to undertake assertive military initiatives to create "facts on the ground" in support of its territorial claims over features in the East and South China Seas.

Russia and China are pursuing asymmetric ways and means to counter U.S. conventional capabilities, thereby increasing the risk of miscalculation and the potential for military confrontation with the United States, its allies, and partners. Both countries are developing counter-space military capabilities to deny the United States the ability to conduct space-based intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR); nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3); and positioning, navigation, and timing. Both seek to develop offensive cyberspace capabilities to deter, disrupt, or defeat U.S. forces dependent on computer networks. Both are fielding an array of anti-access area denial (A2/AD) capabilities and underground facilities to counter U.S. precision conventional strike capabilities and to raise the cost for the United States to reinforce its European and Asian allies and partners. While nuclear weapons play a deterrent role in both Russian and Chinese strategy, Russia may also rely on threats of limited nuclear first use, or actual first use, to coerce us, our allies, and partners into terminating a conflict on terms favorable to Russia. Moscow apparently believes that the United States is unwilling to respond to Russian employment of tactical nuclear weapons with strategic nuclear weapons.

The United States does not wish to regard either Russia or China as an adversary and seeks stable relations with both. We continue to seek a dialogue with China to enhance our understanding of our respective nuclear policies, doctrine, and capabilities; to improve transparency; and to help manage the risks of miscalculation and misperception. The United States and Russia have in the past maintained strategic dialogues to manage nuclear competition and nuclear risks. Given Russian actions, including its occupation of Crimea, this constructive engagement has declined substantially. The United States looks forward to a new day when Russia engages with the United States, its allies, and partners transparently and constructively, without aggressive actions and coercive nuclear threats.

Nevertheless, this review candidly addresses the challenges posed by Russian, Chinese, and other states' strategic policies, programs, and capabilities, particularly nuclear, and the flexible, adaptable, and resilient U.S. nuclear capabilities required to protect the United States, allies and partners.

OTHER NUCLEAR-ARMED STATES HAVE NOT FOLLOWED OUR LEAD

Despite concerted U.S. efforts to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in international affairs and to negotiate reductions in the number of nuclear weapons, since 2010 no potential adversary has reduced either the role of nuclear weapons in its national security strategy or the number of nuclear weapons it fields. Rather, they have moved decidedly in the opposite direction. As a result, there is an increased potential for regional conflicts involving nuclear-armed adversaries in several parts of the world and the potential for adversary nuclear escalation in crises or conflict.

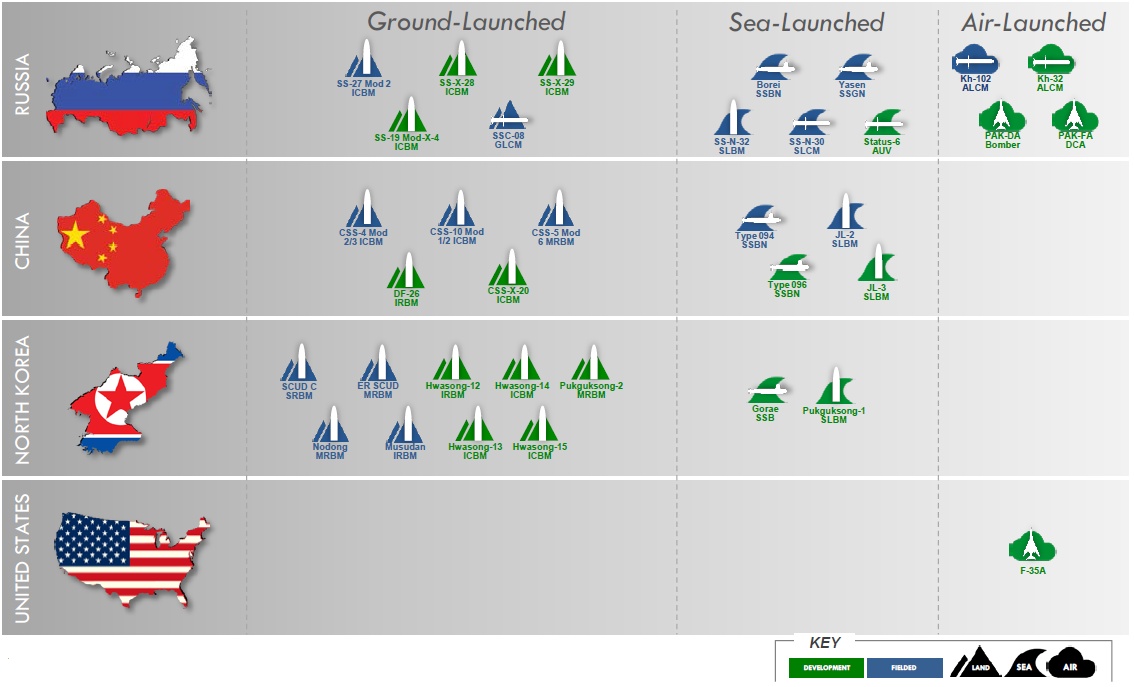

Figure 1 illustrates the marked difference between U.S. efforts to reduce the salience of nuclear weapons and the contrary actions of others over the past decade.

NUCLEAR DELIVERY SYSTEMS SINCE 2010

Figure 1. Nuclear Delivery Systems Since 2010

Data provided by the DoDRUSSIA

Russia considers the United States and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to be the principal threats to its contemporary geopolitical ambitions. Russian strategy and doctrine emphasize the potential coercive and military uses of nuclear weapons. It mistakenly assesses that the threat of nuclear escalation or actual first use of nuclear weapons would serve to "de-escalate" a conflict on terms favorable to Russia. These mistaken perceptions increase the prospect for dangerous miscalculation and escalation.

Russia has sought to enable the implementation of its strategy and doctrine through a comprehensive modernization of its nuclear arsenal. Russia's strategic nuclear modernization has increased, and will continue to increase its warhead delivery capacity, and provides Russia with the ability to rapidly expand its deployed warhead numbers.

In addition to modernizing "legacy" Soviet nuclear systems, Russia is developing and deploying new nuclear warheads and launchers. These efforts include multiple upgrades for every leg of the Russian nuclear triad of strategic bombers, sea-based missiles, and land-based missiles. Russia is also developing at least two new intercontinental range systems, a hypersonic glide vehicle, and a new intercontinental, nuclear-armed, nuclear-powered, undersea autonomous torpedo.

"Nuclear ambitions in the US and Russia over the last 20 years have evolved in opposite directions. Reducing the role of nuclear weapons in US security strategy is a US objective, while Russia is pursuing new concepts and capabilities for expanding the role of nuclear weapons in its security strategy."

U.S. National Intelligence Council, 2012

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Defense Minister General Sergey Shoigu in the National Defense Council Center. (Photo by Russian Ministry of Defense)

Russia possesses significant advantages in its nuclear weapons production capacity and in non-strategic nuclear forces over the U.S. and allies. It is also building a large, diverse, and modern set of non-strategic systems that are dual-capable (may be armed with nuclear or conventional weapons). These theater- and tactical-range systems are not accountable under the New START Treaty and Russia's non-strategic nuclear weapons modernization is increasing the total number of such weapons in its arsenal, while significantly improving its delivery capabilities. This includes the production, possession, and flight testing of a ground-launched cruise missile in violation of the INF Treaty. Moscow believes these systems may provide useful options for escalation advantage. Finally, despite Moscow's frequent criticism of U.S. missile defense, Russia is also modernizing its long-standing nuclear-armed ballistic missile defense system and designing a new ballistic missile defense interceptor.

RESPONDING TO RUSSIA'S INF TREATY VIOLATION

In July 2014, the United States declared Russia to be in violation of the INF Treaty for the development of the SSC-8 ground-launched cruise missile system. The United States has since pressed Russia to return to compliance with the Treaty.

The North Atlantic Council has emphasized that, "full compliance with the INF Treaty is essential," and "identified a Russian missile system that raises serious concerns; NATO urges Russia to address these concerns in a substantial and transparent way." – December 15th, 2017

RESPONSE MEASURES:

Diplomatic Measures – The United States continues to seek a diplomatic resolution through all viable channels, including the INF's Special Verification Commission. Allies have emphasized that a situation whereby the United States and other parties are abiding by the Treaty, and Russia were not, would be a grave and urgent concern.

Economic Measures – The United States has sanctioned Russian companies involved in the development and manufacture of Russia's prohibited cruise missile system.

Military Measures – The United States is commencing INF Treaty-compliant research and development by reviewing military concepts and options for conventional, ground-launched, intermediate-range missile systems.

Russia's increased reliance on nuclear capabilities to include coercive threats, nuclear modernization programs, refusal to negotiate any limits on its non-strategic nuclear forces, and its decision to violate the INF Treaty and other commitments all clearly indicate that Russia has rebuffed repeated U.S. efforts to reduce the salience, role, and number of nuclear weapons.

CHINA

China's CSS-X-20 ICBM on parade in 2015. (Photo by Xinhua News)

Consistent with Chinese President Xi's statement at the 19th Party Congress that China's military will be "fully transformed into a first tier force" by 2050, China continues to increase the number, capabilities, and protection of its nuclear forces. While China's declaratory policy and doctrine have not changed, its lack of transparency regarding the scope and scale of its nuclear modernization program raises questions regarding its future intent. China has developed a new road-mobile strategic intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), a new multi-warhead version of its DF-5 silo-based ICBM, and its most advanced ballistic missile submarine armed with new submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM). It has also announced development of a new nuclear-capable strategic bomber, giving China a nuclear triad. China has also deployed a nuclear-capable precision guided DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile capable of attacking land and naval targets. As with Russia, despite criticizing U.S. homeland missile defense–which is directed against limited missile threats–China has announced that it is testing a new mid-course missile defense system, plans to develop sea-based mid-course ballistic missile defense, and is developing theater ballistic missile defense systems, but has provided few details.

NORTH KOREA

The security environment has worsened given these developments and the threats posed by further proliferation of nuclear weapons.

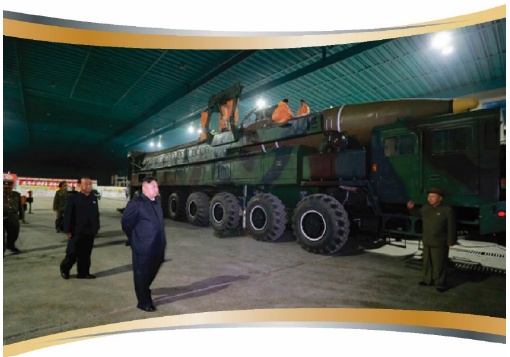

Kim Jong-un inspecting the Hwasong-14 ICBM. (Photo by the Korean Central News Agency)

North Korea has accelerated its provocative pursuit of nuclear weapons and missile capabilities, and expressed explicit threats to use nuclear weapons against the United States and its allies in the region. North Korean officials insist that they will not give up nuclear weapons, and North Korea may now be only months away from the capability to strike the United States with nuclear-armed ballistic missiles. In the past few years, North Korea has dramatically increased its missile flight testing, most recently including the testing of intercontinental-range missiles capable of reaching the U.S. homeland. It has conducted six nuclear tests since 2006, including a test of a significantly higher-yield device. Further, North Korea continues to produce plutonium and highly-enriched uranium for nuclear weapons. Given North Korea's current and emerging nuclear capabilities; existing chemical, biological, and conventional capabilities; and extremely provocative rhetoric and actions, it has come to pose an urgent and unpredictable threat to the United States, allies, and partners. Consequently, the United States reaffirms that North Korea's illicit nuclear program must be completely, verifiably, and irreversibly eliminated, resulting in a Korean Peninsula free of nuclear weapons.

"North Korea's nuclear weapons and missile programs will continue to pose a serious threat to US interests and to the security environment in East Asia in 2017. North Korea's export of ballistic missiles and associated materials to several countries, including Iran and Syria, and its assistance to Syria's construction of a nuclear reactor, destroyed in 2007, illustrate its willingness to proliferate dangerous technologies."

Director of National Intelligence, Daniel R. Coats, Worldwide Threat Assessment, 2017

North Korea's continued pursuit of nuclear weapons capabilities poses the most immediate and dire proliferation threat to international security and stability. In addition to explicit nuclear threats enabled by North Korea's development of nuclear weapons and delivery systems, North Korea poses a "horizontal" proliferation threat as a potential source of nuclear weapons or nuclear materials for other proliferators. North Korea's nuclear weapons program also increases nuclear proliferation pressures on non-nuclear weapon states that North Korea directly and explicitly threatens with nuclear attack.

IRAN

Iranian test launch of a modified Fateh-110. (Photo by the Iranian Ministry of Defense)

Iran, too, poses proliferation threats. Iran's Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has most recently stated that, "America is the number one enemy of our nation." While Iran has agreed to constraints on its nuclear program in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), absent extensive international actions many of the agreement's restrictions on Iran's nuclear program will end by 2031. In addition, Iran retains the technological capability and much of the capacity necessary to develop a nuclear weapon within one year of a decision to do so. Iran's development of increasingly long-range ballistic missile capabilities, and its aggressive strategy and activities to destabilize neighboring governments, raises questions about its long-term commitment to foregoing nuclear weapons capability. Were Iran to pursue nuclear weapons after JCPOA restrictions end, pressures on other countries in the region to acquire their own nuclear weapons would increase.

Nuclear terrorism remains a threat to the United States and to international security and stability. Preventing the illicit acquisition of a nuclear weapon, nuclear materials, or related technology and expertise by a violent extremist organization is a significant U.S. national security priority. The more states–particularly rogue states–that possess nuclear weapons or the materials, technology, and knowledge required to make them, the greater the potential risk of terrorist acquisition. Further, given the nature of terrorist ideologies, we must assume that they would employ a nuclear weapon were they to acquire one.

UNCERTAINTIES REGARDING THE FUTURE SECURITY ENVIRONMENT AND THE THREATS IT MAY POSE

The significant and rapid worsening of the international security environment since the 2010 NPR demonstrates that unanticipated developments and uncertainty about near- and long-term threats to the United States, allies, and partners are factors we must consider in formulating U.S. nuclear policy, strategy, and posture. These uncertainties are a concern in the near term, and potentially profound in the long term. Because this NPR lays the policy, strategy, and programmatic foundation for sustaining and replacing the entire U.S. nuclear force needed to address threats decades into the future, it focuses on the implications of such uncertainties.

There are two forms of uncertainty regarding the future security environment which U.S. nuclear policy, strategy, and posture must take into account. The first is geopolitical uncertainty. This includes the potential for rapid shifts in how other states view the United States, its allies, and partners; changing alignments among other states; and relative power shifts in the international system. The collapse of the government of a nuclear-armed state or a so-called "proliferation cascade" would also fall in this category.

The second form of uncertainty is technological. This includes the potential for unanticipated technological breakthroughs in the application of existing technologies, or the development of wholly new technologies, that change the nature of the threats we face and the capabilities required to address them effectively. For example, breakthroughs that would render U.S. nuclear forces or U.S. command and control of those forces highly vulnerable to attack would dramatically affect U.S. nuclear force requirements, policy, and posture. The proliferation of highly-lethal biological weapons is another example.

Such geopolitical and technological uncertainties are, fundamentally, unpredictable, particularly over the long term. Yet, it is near certain that unanticipated developments will arise. Consequently, we must take them into account to the extent possible as we plan the U.S. nuclear forces and related capabilities needed now and in future decades. Ensuring that U.S. nuclear capabilities have the flexibility and attributes necessary to respond to the possible shocks of a changing threat environment is our responsibility to future generations.

III. WHY U.S. NUCLEAR CAPABILITIES?

"Our nuclear deterrent underwrites all courses of diplomacy and every military operation... there is a direct line between a safe, secure, and reliable nuclear deterrent...and our responsibility as global defenders of freedom."

U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff, General David Goldfein, 2017

U.S. NUCLEAR CAPABILITIES

The fundamental reasons why U.S. nuclear capabilities and deterrence strategies are necessary for U.S., allied, and partner security are readily apparent. As Secretary of Defense Mattis has observed, "a safe, secure, and effective nuclear deterrent is there to ensure a war that can never be won, is never fought." The deterrence effects they provide are unique and essential to preventing adversary nuclear attacks, which is the highest defense priority of the United States.

U.S. nuclear capabilities cannot prevent all conflict or provocations, and should not be expected to do so. But, the U.S. triad of strategic bombers, ICBMs, and SLBMs, supplemented by dual-capable aircraft (DCA), overshadows any adversary's calculations of the prospective benefits of aggression and thus contributes uniquely both to deterring nuclear and non-nuclear attack and to assuring allies and partners. The triad and DCA are essential for these purposes, and will be so for the foreseeable future. As the Bipartisan Congressional Strategic Posture Commission–led by former Defense Secretaries William Perry and James Schlesinger–emphasized in 2009, "The conditions that might make possible the global elimination of nuclear weapons are not present today and their creation would require a fundamental transformation of the world political order." That fundamental transformation has not since taken place, nor is it emerging.

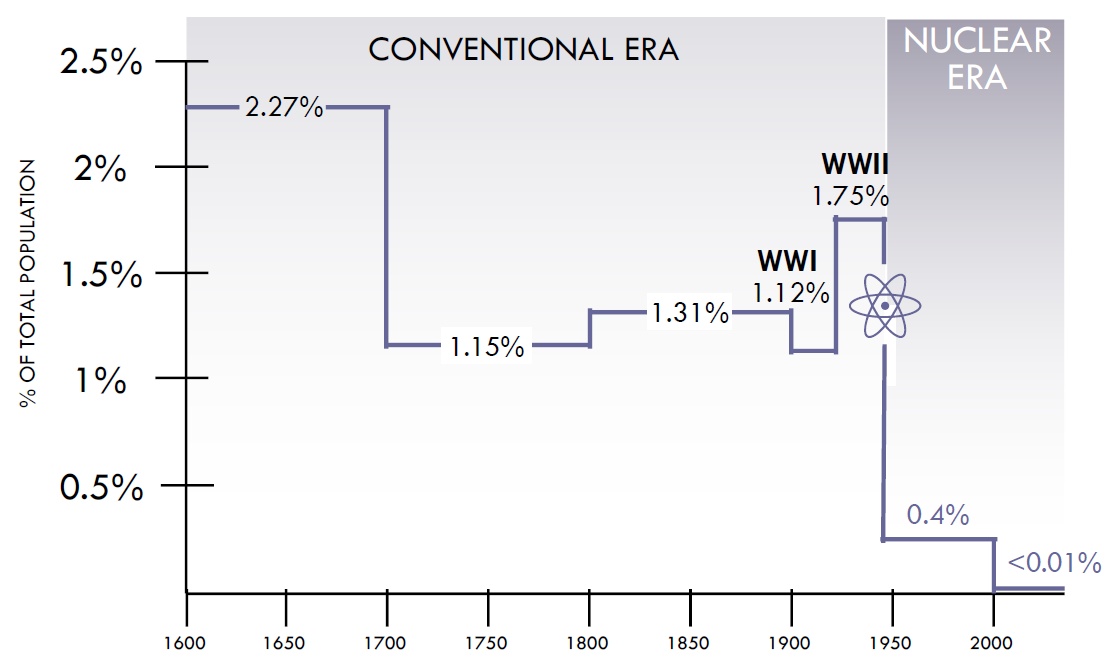

For centuries prior to the era of nuclear deterrence, periodic and catastrophic wars among Great Powers were the norm, waged with ever more destructive weapons and inflicting ever higher casualties and damage to society. During the first half of the 20th century and just prior to the introduction of U.S. nuclear deterrence, the world suffered 80–100 million fatalities over the relatively short war years of World Wars I and II, averaging over 30,000 fatalities per day.

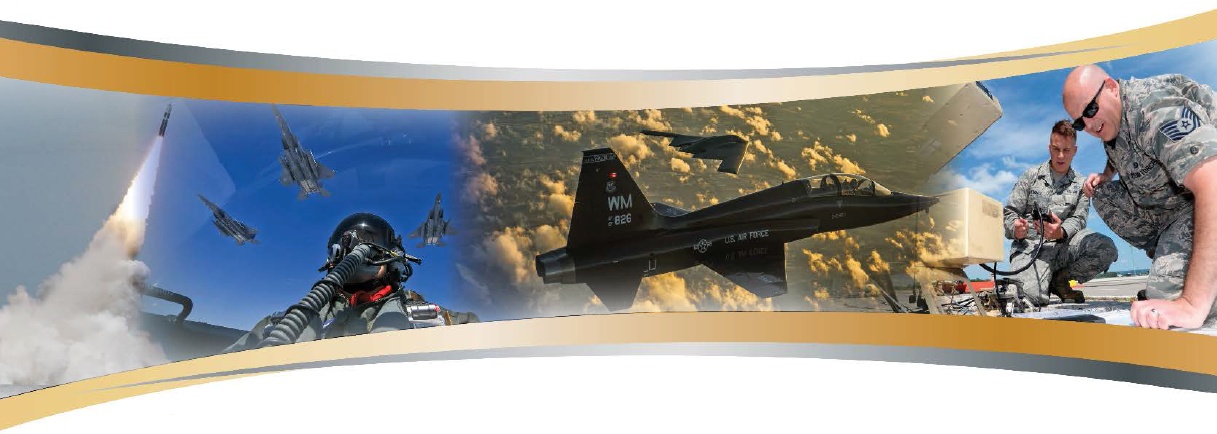

B-2 Stealth Bomber and two F-15 Strike Eagle aircraft.

Air Force Captain discusses U.S. Strategic Command's bomber and intercontinental ballistic missile capabilities with visiting Navy Reserve personnel.

An unarmed AGM-86B Air-Launched Cruise Missile is released from a B-52H Stratofortress.

Machinist's Mate (Weapons) 3rd Class, assigned to the OHIO-class ballistic-missile submarine USS Louisiana (SSBN 743) receives hands-on training inside the Weapons Launch Control Team Trainer at Trident Training Facility at Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor.Since the introduction of U.S. nuclear deterrence, U.S. nuclear capabilities have made essential contributions to the deterrence of nuclear and non-nuclear aggression. The subsequent absence of Great Power conflict has coincided with a dramatic and sustained reduction in the number of lives lost to war globally, as illustrated by Figure 2.

WARTIME FATALITIES % OF THE WORLD POPULATION (CIVILIAN AND MILITARY)

Figure 2. Wartime Fatalities Percentage of World Population

Data from the DoD Historical Office

Non-nuclear forces also play essential deterrence roles. Alone, however, they do not provide comparable deterrence effects, as reflected by the periodic and catastrophic failures of conventional deterrence to prevent Great Power wars throughout history. Similarly, conventional forces alone do not adequately assure many allies and partners. Rather, these states place enormous value on U.S. extended nuclear deterrence, which correspondingly is also key to non-proliferation.

Properly sustained U.S. nuclear deterrence helps prevent attacks against the United States, allies, and partners and the return to the frequent Great Power warfare of past centuries. In the absence of U.S. nuclear deterrence, the United States, allies, and partners would be vulnerable to coercion and attack by adversaries who retain or expand nuclear arms and increasingly lethal non-nuclear capabilities. Until the "fundamental transformation of the world political order" takes place, U.S. nuclear weapons remain necessary to prevent war and safeguard the Nation.

IV. ENDURING NATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND THE ROLES OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS IN U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY STRATEGY

"We believe that by improving deterrence across the broad spectrum, we will reduce to an even lower point the probability of a nuclear clash between ourselves and other major powers."

Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger, 1974

The highest U.S. nuclear policy and strategy priority is to deter potential adversaries from nuclear attack of any scale. However, deterring nuclear attack is not the sole purpose of nuclear weapons. Given the diverse threats and profound uncertainties of the current and future threat environment, U.S. nuclear forces play the following critical roles in U.S. national security strategy. They contribute to the:

- Deterrence of nuclear and non-nuclear attack;

- Assurance of allies and partners;

- Achievement of U.S. objectives if deterrence fails; and

- Capacity to hedge against an uncertain future.

These roles are complementary and interrelated, and we must assess the adequacy of U.S. nuclear forces against each role and the strategy designed to fulfill it. Preventing proliferation and denying terrorists access to finished weapons, material, or expertise are also key considerations in the elaboration of U.S. nuclear policy and requirements. These multiple roles and objectives are the guiding pillars for U.S. nuclear policy, strategy, and requirements.

DETERRENCE OF NUCLEAR AND NON-NUCLEAR ATTACK

The highest U.S. nuclear policy and strategy priority is to deter potential adversaries from nuclear attack of any scale. Potential adversaries must understand that the United States has the will and response options necessary to deter nuclear attack under any conditions.

An unarmed Trident II D5 missile launches from the Ohio-class fleet ballistic-missile submarine USS Maryland (SSBN 738) off the coast of Florida. The test launch was part of the U.S. Navy Strategic Systems Programs demonstration and shakedown operation certification process. The successful launch certified the readiness of an SSBN crew and the operational performance of the submarine's strategic weapons system before returning to operational availability (U.S. Navy Photo)

The specific application of deterrence strategies changes across time and circumstance, but the fundamental nature of deterrence endures: it is about decisively influencing an adversary's decision calculus to prevent attack or the escalation of a conflict. Potential adversaries must understand that aggression against the United States, allies, and partners will fail and result in intolerable costs for them. We deter attacks by ensuring the expected lack of success and prospective costs far outweigh any achievable gains.

U.S. deterrence strategy has always integrated multiple instruments of national power to deter nuclear and non-nuclear attack. Integrating and exercising all instruments of power has become increasingly important as potential adversaries integrate their military capabilities, expanding the range of potential challenges to be deterred. This is particularly true of threats from potential adversaries of limited nuclear escalation and non-nuclear strategic attack.

For U.S. deterrence to be effective across the emerging range of threats and contexts, nuclear-armed potential adversaries must recognize that their threats of nuclear escalation do not give them freedom to pursue non-nuclear aggression. Potential adversaries must understand that: 1) the United States is able to identify them and hold them accountable for acts of aggression, including new forms of aggression; 2) we will defeat non-nuclear strategic attacks; and, 3) any nuclear escalation will fail to achieve their objectives, and will instead result in unacceptable consequences for them.

For effective deterrence, the United States will acquire and maintain the full range of capabilities needed to ensure that nuclear or non-nuclear aggression against the United States, allies, and partners will fail to achieve its objectives and carry with it the credible risk of intolerable consequences for the adversary. U.S. forces will ensure their ability to integrate nuclear and non-nuclear military planning and operations. Combatant Commands and Service components will be organized and resourced for this mission, and will plan, train, and exercise to integrate U.S. nuclear and non-nuclear forces and operate in the face of adversary nuclear threats and attacks. The United States will coordinate integration activities with allies facing nuclear threats, and will examine opportunities for additional allied burden sharing in the nuclear deterrence mission.

An important element of maintaining effective deterrence is the articulation of U.S. declaratory policy regarding the potential employment of nuclear weapons:

The United States would only consider the employment of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States, its allies, and partners. Extreme circumstances could include significant non-nuclear strategic attacks. Significant non-nuclear strategic attacks include, but are not limited to, attacks on the U.S., allied, or partner civilian population or infrastructure, and attacks on U.S. or allied nuclear forces, their command and control, or warning and attack assessment capabilities.

The United States will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapons states that are party to the NPT and in compliance with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations.

Given the potential of significant non-nuclear strategic attacks, the United States reserves the right to make any adjustment in the assurance that may be warranted by the evolution and proliferation of non-nuclear strategic attack technologies and U.S. capabilities to counter that threat.

To help preserve deterrence and the assurance of allies and partners, the United States has never adopted a "no first use" policy and, given the contemporary threat environment, such a policy is not justified today. It remains the policy of the United States to retain some ambiguity regarding the precise circumstances that might lead to a U.S. nuclear response.

In addition, the United States will maintain a portion of its nuclear forces on alert day-today, and retain the option of launching those forces promptly. This posture maximizes decision time and preserves the range of U.S. response options. It also makes clear to potential adversaries that they can have no confidence in strategies intended to destroy our nuclear deterrent forces in a surprise first strike.

The de-alerting of U.S. ICBMs would create the potential for dangerous deterrence instabilities by rendering them vulnerable to a potential first strike and compelling the United States to rush to re-alert in a crisis or conflict. Further, U.S. ICBMs are not on "hair-trigger alert," as sometimes mistakenly is claimed. As the bipartisan 2009 Perry-Schlesinger Commission report stated, hair trigger alert "is simply an erroneous characterization of the issue. The alert postures of both countries [the United States and the Russian Federation] are in fact highly stable. They are subject to multiple layers of control, ensuring clear civilian and indeed Presidential decision-making." Over more than half a century, the U.S. has established a series of measures and protocols to ensure that ICBMs are safe, secure, and under constant control. Any U.S. decision to employ nuclear weapons would follow a deliberative process. Finally, the United States will continue its long-standing practice of open-ocean targeting of its strategic nuclear forces day-to-day as a confidence and security building measure.

ASSURANCE OF ALLIES AND PARTNERS

The United States has extended nuclear deterrence commitments that assure European, Asian, and Pacific allies. The United States will ensure the credibility and effectiveness of those commitments.

U.S. Air Force F-35A Lightning IIs and Japanese Air Self Defense Force F-15 Eagles fly in formation during bi-lateral training December 4, 2017, over the Pacific Ocean. (U.S. Air Force photo)